There’s a lot of programmers out there attending daily “Stand-Ups”, Sprint Planning meetings and Retrospectives, watching “Burn Down” charts, and worrying about “Velocity”. All the time thinking, “What a lot bureaucratic nonsense, just let me program!”

The truth is that there’s just one simple purpose of Agile:

That’s it.

Everyone Learns During the Project

Think about it.

At what point in a project do you know the least about everything you need to know in order to succeed? A what point do you know the most?

The start of the project is when your knowledge is at its absolute lowest point. Some of the things the developers don’t know yet:

- The feature set

- The constraints

- What tools you are going to use

- What the technical challenges will be

- How the product should interact with users

- How the product will alter the business process

And it’s not just the programmers that are suffering from this lack of knowledge. The customers (whomever is going to be using your new system) really don’t know what they want. They can’t, because they don’t know what the Team can do.

The One Fundamental Truth About Building a System

Over the years, I’ve built tons and tons of applications for in-house use by the companies I’ve worked for. I have found that there’s one supreme and inescapable factor that no one ever told me about:

I’ve sat in countless meetings with programmers and users; and participated in countless discussions about requirements and user interfaces and business processes. And in pretty much all of those meetings it really felt like the users understood what the product was going to be. I’ve listened while they’ve picked over details of requirements, argued amongst themselves about priorities and business processes, and generally behave like they get it.

In virtually all of those cases, it’s been pretty clear that all of the developers are on the same page. They may disagree about some details, but they have a shared understanding of the main concepts of whatever was we were discussing. They are pondering the implications of the design, how they’ll wrestle the information out of the database, what the performance bottlenecks might be. But they’re all picturing the same thing.

Then, later - sometimes days, sometimes weeks or months later - it becomes clear that each of the customers had completely different ideas about what the product would look like. Most often, this is when they actually get a chance to use the product.

My experience is that you cannot avoid this.

- Detailed requirements won’t fix it.

- Users don’t read them (not really), even if they have to sign off on them.

- If they do read them, they won’t actually understand them properly.

- Mock-ups don’t work.

Customers will look at them and get a surface understanding of what a screen might look like, but they won’t actually think about what it means, and what it implies about the system’s design. - Prototypes fail.

There seems to be a mental loophole - that this isn’t actually the real product - that lets the customers off the hook about really engaging with a prototype. Honestly, mock-ups are quicker and get you just as far.

So what can you do?

Deliver an actual, working product as soon as possible

It doesn’t have to be - actually, it shouldn’t be - the final, complete product. Maybe it’s just a single screen, or even a menu, or a report. Something where you can say, “Unless you want changes, this is it. This is what you’ll be using”.

There’s something about that flips a switch in the people’s minds. Suddenly, they start wondering why the data is presented a certain way, why some element that they’ve never told the developers about is missing, and maybe how this horrible thing is never going to work for them.

More than once I’ve had a team told, “If it can’t do this vital thing I never told you about, I might as well just go back to using a pencil and paper!”

Think about how much better it is to be told that a week or two into a project, and not six months later when you’ve baked all kinds of assumptions into your design.

This is One of the Problems Agile Helps to Solve

The Agile Manifesto doesn’t talk about Scrum or Kanban, or Daily Stand-ups or any of that. It talks about a set of values and finding a better way to build software.

There’s a second page, with “Agile Principles”. The first three are these:

Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.

Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale.

This is describing an “iterative, incremental” approach to development which leads to an evolutionary design of the system. It’s also the only part of the Manifesto that comes close to describing a process of building software.

Progress == Working Software

There’s one other principle which ties this all together:

Working software is the primary measure of progress.

This is a critical concept. A Gantt chart or a “Requirements Specification” document isn’t “progress”. It’s not a result. It’s a throw-away artifact on the way to progress. If you spend 6 months gathering and documenting requirements, building a system design and making a schedule, how much progress have you made? Zero!

How can this be?

Think about it. How valuable is a Requirements Specification if it’s wrong? Not much, right? What’s the chances that a document created right at the beginning of a project, before any users see any working software is going to be reasonably correct?

What would happen if you built the first little bit of the application based on the requirements and the customers said, “Sorry, that’s not what we need”?

What if there’s some new revelation in that feedback, and that new information ripples through the whole system design making little changes everywhere?

Now, how much progress do you think was contained in your Requirements Specification? How much of that first 6 months was wiped out after the first demo of working software after 2 weeks of programming?

How This is Different From Waterfall

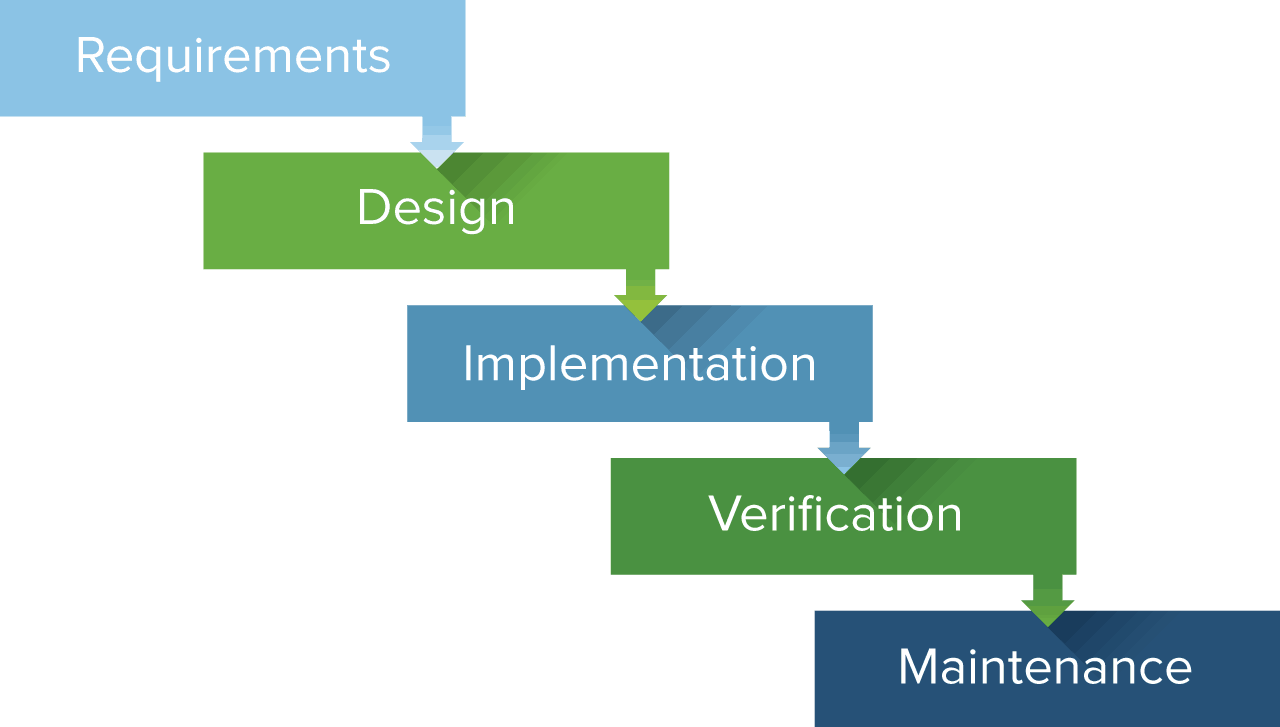

The idea behind Waterfall is to collect all of the requirements up-front, document them and get customer sign-off indicating that this is, in fact, an accurate description of exactly what they want. Then the requirements are analyzed and a system design is created. From that, the technical specifications for programming are written up, estimates around the programming time are determined and a schedule is drawn up. Programming begins and the system is built, after which it is tested and then released to the customer for acceptance testing. Finally, it is deployed and goes into maintenance mode.

This is a very standard project management practice which is used in a many industries with a great deal of success. It tends fails catastrophically for many, if not most, software projects.

This is a very standard project management practice which is used in a many industries with a great deal of success. It tends fails catastrophically for many, if not most, software projects.

Why?

Virtually all software projects have some aspect of exploration and experimentation in them, of doing something that no one has done before. Otherwise, it would be cheaper to buy it off-the-shelf or to hire someone who’s done in many times before.

It turns out that the idea that you could somehow spend weeks or months collecting detailed requirements and having them verified by the customer at the beginning of the project is flawed. The idea that you can create a perfect design up-front, and then schedule the programming from that design just doesn’t work in real life.

Here’s What Usually Happens

In a real-life Waterfall systems project, you can expect the follow things to happen:

- The customer knows they’re locked in on the requirements after they sign off, so they defensively ask for everything that can possibly think of because they cannot add it later.

- The customer gives up on the requirements document after the first hundred pages.

- The customer nit-picks a few details in the requirements but misses some really important implications.

- The customer has no hope of understanding the design documents, if they ever see them.

- The programming specification follows the design which is based on flawed/incomplete requirements.

- There’s a Gantt chart!

- Six months into the project, programming starts.

- Programmers encounter difficulties from the very first module they build:

- Task #2 starts a bit later than the Gantt chart says.

- Task #3 starts even a bit later than that…

- Programmer testing eventually consists of, “It compiles!”.

- QA will catch the obvious bug.

- It will come back as a new bug-fix task with new time allocated.

- Programming looks like it’s sticking a little closer to the Gantt chart.

- Something actually takes less time than the Gantt chart said, use up all the time anyways.

- Programmers discover huge flaws in the design. Nothing can be done about this.

- The Project Manager spends all of their time stretching the Gantt chart out, sweating over the Critical Path.

- If there are demos throughout the project, anything that the customer sees that seems wrong needs to become a “Change Request”:

- Change Requests flow through some approval process.

- Change is highly resisted.

- Heated arguments centre around whether something is a “Bug”, an “Enhancement” or a “Change”. Somehow this is important.

- There is talk of “Phase II”

- Eventually, possibly, something is delivered. Unfortunately:

- It’s bigger than it needs to be.

- It’s missing critical stuff nobody thought of at the beginning.

- Some of that missing critical stuff is going to be very difficult to add, since the system was designed without it.

- It’s late.

- It’s missing stuff that was jettisoned to meet the deadline that wasn’t met.

- The code quality is low because every step of the programming was rushed to stick to the Gantt chart.

- Nobody wants to go through this again with Phase II - but what’s the choice?

As bad as this sounds, this would actually have been considered a pretty good outcome 20 years ago. Everyone that was around back then had heard of a least a few projects that made it to within 6 weeks of the “Go Live” date, and then suddenly asked for another 6 months and $1M to complete the project. And then got shut down. It was common.

Surveys back then estimated that more than 50% of all IT projects were either cancelled or considered failures. The number of IT projects that came in, “On time, on scope and on budget”, was laughably small.

When Waterfall failed, it was usually blamed on bad requirements gathering at the beginning. Which is absolutely true. The fallacy is that somehow - maybe with more time and better skilled staff - you can actually create complete and accurate requirements on day one for a software system that hasn’t been built yet.

This is the Real Point of Agile

Most of us lived in this world of failure. There had to be a better way, and we needed to start doing something different in order to succeed.

Agile works better because it is based on two critical assumptions:

- Better decisions are made when there is more information available, and information grows over time. All decisions should be deferred as long as reasonably possible.

- Non-developers are only be fully engaged in the process when they can interact with working software.

Not that any of this makes building systems easy, but it does describe a process which has a much better chance of success.

What About Scrum?

Even though it doesn’t work very well, corporations lean towards Waterfall because it gives an impression of control and predictability that fits in well with the way that they are organized. Agile scares them because it admits that these are often illusionary when it comes to software development.

So, here comes Scrum. Scrum provides two vital things:

Structure for the Team

Scrum creates a framework which allows a team to organize within a corporation which isn’t Agile; that evaluates employees individually instead of as a team, and that doesn’t really understand the complexity of the work that they do.

The sharp division of responsibilities between the developers and the customer, with the emphasis on ownership of the feature set on the customer side (the term, “Product Owner” is not an accident) leaves the technical implementation completely under control of the developers.

There’s also an awareness that work is work, whether it’s a bug fix, a new feature, a change or an enhancement. Nobody argues about whether something is a bug fix any more, it goes on the Product Backlog, gets prioritized, estimated and scheduled just like any other work.

The cadence of regular Sprints creates a structure around which a team can learn to collaborate and organize a large project into small, manageable pieces. The lock-down of priorities which occurs at the beginning of a Sprint insulates the Team from organizational noise and forces the company to respect the Team’s need for focus while they work.

Structure for the Organization

Scrum provides a framework that allows Agile to be more easily integrated with the controls of organization that isn’t Agile.

Most organizations understand commitments and deadlines, and have a need to keep the leadership informed about progress and delays. While Agile appears to take away much of the ability to budget and plan, Scrum gives back transparency. Lots of transparency.

Now there’s a Product Backlog with a list of everything left to do. The most important stuff is at the top, and probably has some kind of rough estimate around it. The Team estimates and makes commitments to complete a certain amount of work every Sprint. How much they can get done in a Sprint even has a name, “Velocity”, and it can be measured! We can use Velocity and the Product Backlog to predict things like completion dates!

What About the Stand-Ups?

The Daily Stand-Up meeting is supposed to be about each team member informing the rest of the Team about how they are doing on the work. It’s not about reporting progress to the Scrum Master or management, but to each other. It’s supposed to be held standing up to keep it short and, therefore, focused and meaningful.

If the Team hates the Stand-Up, even if it’s short, it’s a pretty good sign that they’re not really collaborating. Probably, they’re dividing up the work for the Sprint into tasks and “assigning” them to team members who then go off and work alone. That’s what most teams do. It’s easy, but it’s not the way it’s supposed to work.

Ideally, the entire team should share the responsibility for all of Sprint deliverables collectively and individually. The Daily Stand-Up should be everyone’s opportunity to make sure that their teammates are staying on track, to spot problems and help if they can. If a team member comes to the Stand-Up day after day, reporting that they are still working on the same task that was supposed to take 3 hours, then the Team should right on top of that. Is there anything they can do to help? What’s that going to mean for the rest of the Sprint deliverables?

It’s possible that a team could become so seamless at collaborating that the Daily Stand-Up is no longer necessary, but a team like that would probably find real value in the Stand-Up and keep it.

Can You Alter or Abandon Scrum?

Certainly, a team can outgrow Scrum. And Scrum is just one way of doing Agile development, not the only way.

It’s also possible that an organization might become comfortable enough with the results from a team to stop worrying about burndown charts and velocity. It’s a matter of trust built up through success.