Introduction

If you’re old enough and you live in North America, you probably remember Ronco and their late night “Infomercials”. One of the most memorable of these was for their “Showtime Rotisserie”. Take a look, and make note of the catch phrase:

“Put the chicken in the oven, follow the instructions, and… SET IT AND FORGET IT!”

But what does this have to do with programming in JavaFX?

More than you’d think, because this is exactly the process you should follow when you’re creating a screen and the individual elements that make up a screen:

- Create the widget

- Configure the widget

- Bind the widget

- SET IT in the layout AND FORGET IT!

How Does This Work?

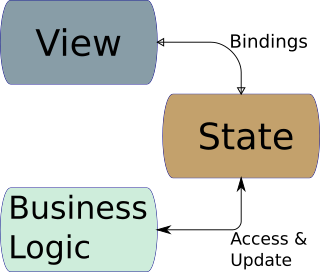

The most important idea here is that “State” and “View” are not the same thing. In fact, they are quite different:

- State

- State is the data related to a UI. Generally it is going to be reflected in the information shown on the screen, or the presentation of that data on the screen. In JavaFX, state is usually held in Observable objects of some sort.

- View

- The View is the visual presentation on the screen, and the component of your system that the user will directly interact with.

In JavaFX, the components that make up the View are generally bound to components of State. In this way, changes to the State will be immediately reflected in the View, and changes made in the View are immediately reflected in State. Doing this allows the rest of your application to access, modify and react to changes in State without any dependency on the nature of the View.

In practice, it looks like this:

Why is This Important?

Coupling.

It’s all about coupling or, rather, not coupling.

A View can be a complicated thing. There are all sorts of visual and user experience factors that need to be dealt with and potentially you might need to account for accessibility issues or different client devices. Putting code in there that calls out to business logic, or providing hooks to allow external classes to update data in the View directly quickly builds up the complexity of your View and clutters it with stuff that’s not, strictly speaking, “View”. Not to mention that you’re going to need to write some code to get the data out of your View and expose it to external classes.

But, as you can see from the diagram above, the View and the Business Logic are ignorant of each other, so neither one can become bogged down with the complexities of the other. And changes to one will not require changes to the other.

JavaFX provides an incredibly complete toolkit to get rid of all of that complexity. It’s called “Binding”.

With Binding you can create an external class to hold all of the elements of State as Observable object fields. Then you pass that class to your View and it can bind the individual elements of State to the various components and their properties in the View. Once you’ve done that, you can just about forget about the inner workings of your View when you’re writing your business logic.

This Idea Scales!

You can think of this concept like a fractal diagram. At a big picture level, you have a UI with one or more screens involved with it. Together those screen comprise a single View, and would have a single State. But each of those screens is a View itself, and has an associated State. Maybe some of those screens have sections which are written as custom components, each of which can be considered to be a View with their own State. And when you look into the layouts of any of these screens you see sub-layouts and containers, each of which can be considered a View with an associated State.

Finally, you get down to the individual Nodes in the layouts. Each of those can be considered a View, and each of them would have their own associated State.

No matter what level you’re looking at, the process is always the same. Create the View, configure the View and bind it to State, then set it in a layout and FORGET IT.

State Data is Not View Data

This is a subtle but important distinction.

All of the data in State is in State because it is needed for the View, but it’s not the data of the View.

Let’s look at some examples to understand what this means.

-

Data in State is in its native format.

For instance, if you have a data element which is a whole number, it should be represented in State as anIntegertype. The View might need to transform it into some other type in order to display it on the screen - probably aString, but maybe anEnum. Maybe the View needs to change it into a decimal between 0 and 1.0 so that it can be shown in aProgressBar. Leave it as an Integer in State, and let the View deal with the presentation. -

Data in State is organized to be independent of the View.

Think about a name. How should a name be displayed? Last name, comma, first name? First name, space, last name? Just last name? Just first name? Name should probably be stored in State as two fields; first name and last name. That way the View alone can be responsible for how the presentation is done. -

Data in State is identified by business meaning.

As an example, let’s imagine that some value needs to be shown in a different colour if it’s in an error state, so you create a separate field in State to indicate this. What kind of data should it be, and what do you call it? Well, you don’t make it typeColourand call itXyzFieldColour. Something like aBooleantype calledAbcValueExceedsLimit, would be much better. Nor would you make it aBooleancalledXyzInRed. That wouldn’t make any sense to the Business Logic module - and what would happen if the View was changed so that it in purple? Let the View interpret the meaning and decide about the presentation.

Notice a trend? State is designed to convey meaning to the data, the View is designed to handle presentation of the data. Keep these two roles strictly separated.

How Do You Do This?

At the Top Level

First, use some framework that separates View, State and Business Logic. I’ve found that my MVCI structure works well.

With MVCI there is a Controller which instantiates the State (the “Model”) and passes a reference to both the View and the Interactor (the Business Logic) in their constructors. The Model is just a POJO with the fields made up of JavaFX Observable objects.

As for the “Set It and Forget It” part, the Controller exposes a single method called getView() which returns a Region. Whatever class instantiates the Controller (very often something like Application which creates the Stage and Scene), then calls this method to get a very generic layout class which it can place into a Scene or another layout.

The result is that the entire MVCI construct presents itself as a generic Region to the rest of your application’s GUI. Whatever information it needs to bootstrap itself is supplied through constructor parameters or pulled through an external API in the Interactor. Your application’s GUI instantiates it, sets it in a Scene or layout, and FORGETS IT.

Inside the Layout

The best practice here is to stick to the “Single Responsibility” Principle, and “Don’t Repeat Yourself” (or, “DRY”), and things should just naturally fall in place.

Let’s say that your main layout is a BorderPane. You’re going to have some quantity of zones in the BorderPane that you’ll want to populate and configure. Don’t stick it all in one, giant method. Have a top level method that just has one line of code for each zone, and that line calls some other method to construct the layout that goes into that zone. Something like this:

private Region buildLayout() {

BorderPane results = new BorderPane();

results.setTop(createTop());

results.setCenter(createCentre());

results.setBottom(createBottom());

return results;

}

Now buildLayout() has just one responsibility - to create the main layout.

Also note that buildLayout() doesn’t return BorderPane, it returns Region. There’s not much you can do with Region other than put it in a Scene or layout and set some constraints on its size. You certainly can’t muck about with its contents or call setRight() on it. This pretty much forces whatever calls buildLayout() to, “Set It and Forget It”.

The same thing goes for createTop(), createCentre() and createBottom(), all of which are going to return either Node or Region. You can see that buildLayout() simply calls those methods, takes the results and sets it in the BorderPane and then forgets them.

Like I said earlier. This concept is fractal in nature. If createCentre() is going to create a BorderPane itself, then I’d expect it to look very much like buildLayout() in its structure. And so on…

BTW: Don’t give those methods names like, createCentre(). Call them something meaningful, like createDataEntryBox() or whatever. Anything but, createCentre().

Another important point here is that the BorderPane has been named, “results”. This has a huge psychological impact as it really says, “I have no meaningful existence as an object outside of the context of this method”. That makes it very clear that you are going to “Set It and Forget It”.

At the Node Level

Individual Node declaration tends to be more about configuration than layout, but the ideas are very much the same. Let’s look at a simple example:

private Node createNameBox() {

Label prompt = new Label("Name:");

prompt.getStyleClass().add("prompt-label");

Label name = new Label();

name.textProperty().bind(state.nameProperty());

name.getStyleClass().add("data-label");

return new HBox(5, prompt, name);

}

There’s a few things to make note of here:

- The returned

HBoxis never instantiated as a variable. This is the end goal for “Set It and Forget It”. - This method returns

Node, notHBox. No calling method can use it as anHBox. - These two

Labelsare only instantiated as variables because they need to be configured. - This method is violating the “Single Responsibility Principle”, as it both performs layout and configures the

Nodes.

This last point is important, because it suggests some significant improvements which are going to get us even closer to “Set It and Forget It” - remember how I said this would follow naturally?

Let’s do this:

private Node createNameBox() {

return new HBox(5, createStyledLabel("Name:", "prompt-label"),

createBoundStyledLabel(state.nameProperty(), "data-label"));

}

private Node createStyledLabel(String contents, String style) {

Label label = new Label(contents);

label.getStyleClass().add(style);

return label;

}

private Node createBoundStyledLabel(ObservableStringValue contents, String style) {

Label label = new Label();

label.TextProperty().bind(contents);

label.getStyleClass().add(style);

return label;

}

Now the configuration code is completely divorced from the layout code, so there’s no need to have any local variables in createNameBox(), and it’s become just one line.

If you think about it a little bit, you’ll see that createStyledLabel and createBoundStyledLabel have absolutely zero code in them which is specific to this, or any, particular layout. You could split them off into a static utility class somewhere and never have to think about the those Labels as Labels ever again.

Kotlin has “scope” functions that really bludgeon you over the head with this idea of “Set It and Forget It” because you can completely dispense with explicitly instantiating variables for these Labels:

fun createBoundStyledLabel(contents : ObservableStringValue, style: String) : Node = Label().apply{

styleClass += style

textProperty().bind(contents)

}

In truth, the apply function has an implicit receiver of this, which can then be omitted when referencing fields or methods of the Label in the scope of apply. But the impact is still huge - it’s never given a name and it’s a Label only in the scope of the apply.

General Guidelines

Single Responsibility and DRY Will Get You There

JavaFX is chock full of repeated boilerplate that you need to get out of your layout code. Try to keep configure the amount of configuration code (things like binding and setting styles) in your layout code down to a minimum. Write helper/builder methods with parameters to handle repeated configuration operations.

As you do this, you get closer and closer to “Set It and Forget It”.

Avoid Nodes as Fields

Declaring a Node object as field in your View is essentially announcing that you’re planning on referencing it as a global variable throughout the class. That’s pretty much the opposite of, “Set It and Forget It”.

So don’t do it.

Think about why you want to make it a field. What aspect of that Node do you want to access from all over your View? Maybe you could move that information into your State?

Don’t Extend, Use Builders

The straight-ahead approach to build a View is to take a class like BorderPane and extend it.

Don’t do that.

Create a ViewBuilder class which implements Builder<Region>. Call its build() method to create your view, and return it as a Region.

The important point here is that once your application has received a Region there’s not much it can do with it except put it in a layout and forget it.

Views and ViewBuilders Have no Public Methods

…other than build(), and their constructors.

Every new non-private method that you add to a View or ViewBuilder increases the coupling with the other components of your application. This is the opposite of what you want to achieve.

Who’s going to call these methods?

Probably your business logic. And that’s bad because it means that your business logic is now becoming entangled with the implementation of the View.

Builders and Builder Methods Return Node or Region

The higher you can go up the tree structure of JavaFX objects with your return types, the less functionality you’ll expose to the rest of your application, and the more freedom you’ll have to design the inner workings of that View without worrying about compatibility with any other part of your application.

Don’t Put Business Rules in Your View

This is one of the primary guidelines to decide “What goes where?”

Imagine that you have a screen with some kind of warning icon on it somewhere. That icon is invisible until one of a subset of choices in a ComboBox is selected. It’s tempting to say, “This is View, I can bind the Visible property of the icon to the Value property of the ComboBox”.

But is it View?

Not really, the conditions that determine if the warning icon should be shown are really business rules. Somewhere, you need some code that says, “These particular choices are important”. And that code is business logic. So it can’t go in the View.

Far better is to create a Boolean property in State that indicates that whatever condition that would merit a warning has been met. Usually, that kind of a property is going to be a Binding, and the internal logic of the Binding would be set by your business logic class.

It’s important that programmers looking for business logic know where to go to find it. So keep it in one place.

You’re more likely to break this rule when it’s all contained within a single Node. For instance, if you want to change the colour of a Label when it’s value meets certain criteria. It’s so easy to just create a binding that looks at the value and restyles the Label based on that value. But those conditions are business logic.

In truth, the State for that Label actually contains two properties; one for the value and another to convey that some business condition has been met. Once again, that second property is likely to be a Binding that should be defined in your business logic class.

Binding Properties

Bind Node Properties to State First

All of your Nodes should be as independent of each other as possible. So create as much of those dependencies with State as you can, even if this means that you have many Nodes and their properties bound to the same State property.

Create a Property Field in the View, and Bind to It

Imagine that you’ve identified some common aspect of your View that needs to be bound together. It’s not State, because it is completely internal to the presentation of the information in the GUI. As an example, let’s say that you want to have a “Page Down” Button activated whenever a Pane displays a scroll-bar. Rather than binding the Enabled property of the Button to the Visible property of the scroll-bar, create a Boolean property field or variable, call it “PageDownAvailable”, and bind it to the scroll-bar Visible property. Then bind the Disable property of the Button to it.

This is really the best route when the Nodes involved exist in different scopes.

Bind Nodes Properties to Node Properties as a Last Resort

And only do this when the relationship is strictly View. For instance, bind the MaxWidth of an HBox, to the Width of another HBox. Generally, you’re only going to do this when the two Nodes involved have been instantiated in the same scope.

Conclusion

Nothing in this article is particularly complex, or difficult to master.

But none if it is obvious when you’re starting out with JavaFX, and I’ve never seen any article or tutorial that lays it out clearly.

And this approach works. It works really well because it strips out a huge amount of complexity in your design. It’s really amazing how even complicated systems can become almost trivial to execute in JavaFX when you take the right approach - and that all starts by drawing an uncrossable line between presentation and business logic.

I’m not going to try and pretend that there’s anything innovative or unique about the concept of creating a “Presentation Model” and binding it to the View. It’s an idea that’s been around for decades.

But the “Set It and Forget It” philosophy takes this idea and turns it into a practical design pattern that you can implement at every level of your GUI application. I think it’s worth adopting.