Introduction

From time to time the question comes up about Swing vs JavaFX. Which is better? Is Swing dead? Should you convert your old Swing application to JavaFX?

People always tend to focus in these discussions on the look and feel of Swing. Out-of-the-box GUI’s built in Swing tend to look like refuges from the 1990’s, which isn’t surprising considering the age of Swing. JavaFX tends to look more modern by default, although still very “corporate”. But it seems easier to customize the look and feel with JavaFX.

But I’m not sure that any of that is enough reason to go through a painful conversion from Swing to JavaFX.

The most important difference between JavaFX and Swing is that JavaFX is designed to support Reactive GUI development.

When you look at the scope of Observable classes and utilities this - at least to me - becomes obvious.

Yes, Swing does support the “Observer Pattern”, but it is extremely crude compared to JavaFX. The vast library of JavaFX Properties, Bindings, Listeners and Subscriptions, and the way that they are integrated natively into all of the screen Nodes, make it virtually trivial to implement a Reactive framework.

My experience has been that applications architected with a Reactive design are perhaps an order of magnitude easier to implement, enhance and maintain. Now that could be a valid reason to convert a Swing application to JavaFX.

The problem, though, is that it is also possible to write a JavaFX application in an imperative/declarative fashion. And it works, although it’s not as clean as using a Reactive approach.

Even worse, nobody talks about “Reactive JavaFX”. It’s not mentioned at all in the Oracle documentation or tutorials. It’s a shame.

In this article we are going to look at how Reactive GUI’s work, the different kinds of Reactive systems that are available and how JavaFX fits in with those. Then we are going to look at how a Reactive JavaFX system is different from a Declarative/Imperative system, and we’ll see how Reactive design makes the application simpler by removing coupling. Finally, we’ll look at how Reactive Design fits in with frameworks like MVC, MVVM and MVCI.

What is Reactive Design?

Any “Reactive” design involves creating a data representation of the “State” of your GUI. When the values in this State construct change, then the Reactive system will update the GUI such that it reflects those changes.

The layout programmer’s job, therefore, is define how the layout will look and behave with any given set of values in the State.

When you start to work with a Reactive system, you realize that there are two kinds of things that can happen in a GUI:

-

Changes to State

For instance a user types something in a textfield, moves a slider, or selects an item in a list. -

Actions

This could be a user clicking on a button, or actions associated with the user moving a slider or selecting an item in a list.

In a Declarative (or “Imperative”) approach to GUI design, everything is an “action”. For instance, the user types in a textfield, but this affects only the screen until they shift the focus to another field, at which point a “focus lost” action might be triggered that would cause code to run that moves data around or changes the layout.

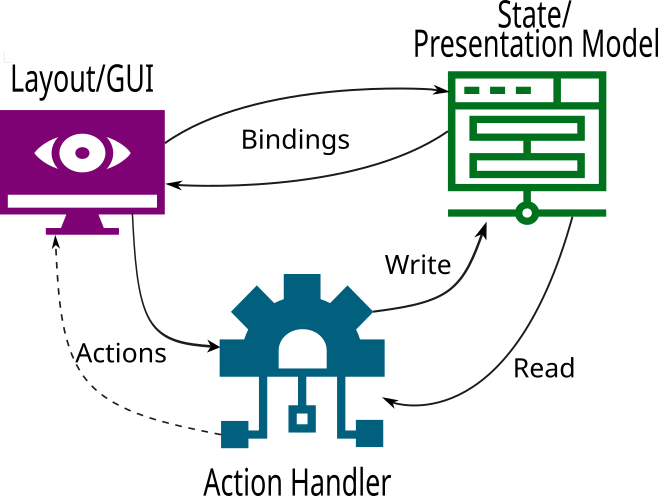

A Reactive system usually looks something like this:

The layout has elements that control how it behaves that are “bound” or “synchronized” in both directions with the “Presentation Model”, which is the data representation of “State”.

Additionally, actions might be triggered by the layout. Whatever handles these actions also has access to the data elements in the Presentation Model, but usually in a more normal read and write manner - not through binding. It is possible that the “Action Handler” could tell the layout to take some action, although I’m not sure that all Reactive systems allow this.

Types of Reactive Systems

Personally, I’ve encountered three different Reactive systems: JavaFX, Jetpack Compose, and React.

Jetpack Compose is the preferred system for devoloping Android applications, while React is for web development and JavaFX, of course, is for desktop applications. I have some experience with Jetpack Compose, and a passing familiarity with React.

From what I have seen, these break down into two different approaches to Reactivity. I’ve never seen them defined anywhere, so I am going to call them “Compositional Reactivity” and “Layout Reactivity”. Let’s take a look at them…

Compostional Reactivity

This is the implementation of Reactivity that is use by both Jetpack Compose and React.

Essentially, the code that “composes” the layout is divided up into snippets, and each snippet is dependent on whatever elements of State that it uses. If one of those State elements changes, then that code snippet (and presumably any code snippets that it calls) will be re-executed and redraw the screen. All of the screen elements themselves are truly static, and depend on the re-execution of the composition code in order to appear to behave dynamically.

With Compositional Reactivity, you expect that your layout code is going to be run over and over again - at least in part. Each time it executes, it will build the static layout according the values in the Presentation Model at the time that it executes.

Here’s an example from the official Jetpack Compose tutorial:

@Composable

fun WaterCounter(modifier: Modifier = Modifier) {

Column(modifier = modifier.padding(16.dp)) {

// Changes to count are now tracked by Compose

val count: MutableState<Int> = mutableStateOf(0)

Text("You've had ${count.value} glasses.")

Button(onClick = { count.value++ }, Modifier.padding(top = 8.dp)) {

Text("Add one")

}

}

}

The @Composable annotation declares this function as something that Jetpack Compose is going to use to build the layout and which is dependent on State. This function creates a Column and sticks a Text and a Button in it.

The line that instantiates count as MutableState<Int> is where it defines the element of State that the this function is dependent on. Changes to count will trigger re-execution of this code - but let’s just call it “recomposition”.

Notice that the Text just shows a static String that includes the current value of count at the time that it executes. There is no way to change the value displayed by a Text.

The Button just increments count. Here you see how an action updates the Presentation Model, and that update triggers the recomposition of the layout.

As soon as count changes, this piece of layout is determined to be defunct and needs to be re-composed, so this function will be re-executed, the Column will be rebuilt and the Text will be recreated and populated with a String that now contains the new value of count.

To the user, it just looks like the value in the Text changed. But from a programming perspective, a piece of the layout has been recomposed.

You can put any logic that you want in there. Try this:

@Composable

fun WaterCounter(modifier: Modifier = Modifier) {

Column(modifier = modifier.padding(16.dp)) {

// Changes to count are now tracked by Compose

val count: MutableState<Int> = mutableStateOf(0)

if (count > 0) {

Text("Glug...glug...glug...")

}

Text("You've had ${count.value} glasses.")

Button(onClick = { count.value++ }, Modifier.padding(top = 8.dp)) {

Text("Add one")

}

}

}

The first time through count will be “0” and that “Glug..glug…glug…” Text will not appear. Every other time, count will be non-zero and that Text will appear.

Layout Reactivity

With “Layout Reactivity” the layout code is executed just once, but the layout itself behaves dynamically in response to changes to the Presentation Model. This is the approach that JavaFX uses.

Let’s see how you would do the same type of counting exercise as in the Jetpack Compose example:

fun waterCounter() : Region = VBox().apply {

val counter :IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(0)

children += Label("Glug...glug...glug...").apply {

visibleProperty().bind(counter.greaterThan(0))

managedProperty().bind(visibleProperty())

}

children += Label().apply {

textProperty().bind(counter.map{ "You've had $it glasses." })

}

childern += Button("Add one").apply {

setOnClick { evt -> counter.value += 1 }

}

}

Here we have a static layout that behaves dynamically: It’s “static” in that layout itself doesn’t change. No Nodes are added or removed from the layout. It behaves dynamically, because the individual Nodes do things in reaction to the Presentation Model.

That “Glug…” Text is always there. However, its visibility is bound to whether or not count is greater than zero. Its managed Property which controls whether or not the layout manager gives it space on the screen is also bound to the same condition. When count is zero, it’s neither visible, nor given any space on the screen.

The text in the second Label is bound to counter through a map{} functiont that provides the rest of the String.

Once again, the Button simply triggers an action that updates the Presentation Model which, in turn, causes the layout to react and change its behaviour.

These are Very Different Approaches

I think you can see that to a user, there is no difference between either approach. The GUI’s appear to behave in an identical manner.

It’s the implementation which is completely different.

In the Jetpack Compose approach, that “Glug…” Text didn’t even exist in the layout before the Button was clicked. In the JavaFX version, it was always there - just invisible.

The truth is that both approaches boil down to the same thing. At some point the screen has to be redrawn to show that “Glug…” Label\Text. But with JavaFX, that redrawing happens deep, deep inside the guts of the Layout Manager, and as programmers we don’t ever need to think about it. In Jetpack Compose and React, that’s just about all that you think about - “How will you build the layout when the data looks like this..or this..or this?”

Obviously, Jetpack Compose and React are far more popular than JavaFX, so when people think about “Reactive” systems, they are probably imagining a Compositionally Reactive design.

How Reactive Design Makes Systems Better

Back in the introduction, I claimed that Reactive Design makes systems nearly an order of magnitude easier to enhance, debug and maintain. Let’s look at how that might be…

The Same Example In an Imperative Design

Before we go any further, let’s look at the example, and how you would write it in JavaFX like it was Swing:

fun waterCounter() : Region = VBox().apply {

val counter : Int = 0

val glugLabel = Label("Glug...glug...glug...")

val countLabel = Label("You've had $counter glasses.")

val button = Button("Add one")

button.setOnAction { evt ->

countLabel.setText("You've had $counter glasses.")

getChildren().setAll(listOf(glugLabel, countLabel, button))

}

children += listOf(countLabel, button)

}

Instead of a Binding, the value of countLabel is changed via setText(), and instead of using a static layout with glugLabel toggling between invisible and visible, the layout is modified to add glugLabel in response to the Button click.

Coupling

One thing you’ll notice in this Imperative example is that we now have variables to hold Labels and Button. That’s because we need references to them so that we can update them from inside the Button action. You’ll also see that button is calling a method on the enclosing VBox - getChildren().

This are examples of “coupling”.

Coupling is probably the single most important factor that makes applications difficult to understand, maintain and enhance.

When we expose glugLabel, countLabel and the enclosing VBox to button, we don’t just reveal their existence, but also their implementation.

Once we’ve shared the implementation details of something, then we’ve created coupling. It’s coupling because we cannot change that implementation without looking at how that implementation knowledge is used through the system.

Even here, where the variable scope is just 10 lines of code, it can cause problems. Imagine that we wanted to change the text of counterLabel to this:

val countLabel = Label("You've had $counter pints of beer.")

We’ll have a problem if we just stop there, because button is going to set it back to "You've had $counter glasses." as soon as it is clicked. Any change to the implementation of countLabel means our application might be broken.

Let’s say that we decided to change our implementation of counterLabel to be something other than a Label. Perhaps an ImageView sprite with a number of Images of different numbers of beer glasses, tied somehow to counter. Now, our Button action won’t work at all, and we’ll have to change its logic to manipulate an ImageView instead. At least here we’ll get a compiler error.

This situation gets worse if button is defined somewhere else. Then, we’ll need to push countLabel and our VBox up to fields in our layout class, so that we can access them with button:

private val countLabel = Label("You've had 0 glasses.")

private val countPane : Pane = waterCounter()

.

.

.

fun waterCounter() : Pane = VBox().apply {

.

.

children += countLabel

.

.

}

.

.

.

fun someOtherPane() : Region = VBox().apply{

.

.

val counter : Int = 0

val glugLabel = Label("Glug...glug...glug...")

val button = Button("Add one")

button.setOnAction { evt ->

countLabel.setText("You've had ${counter++} glasses.")

countPane.getChildren().setAll(listOf(..., glugLabel, countLabel, ...))

}

children += button

}

Now, we need to know the contents of countPane in order to alter it without losing things already in it. Any changes to waterCounter() will require changes to someOtherPane() as well. Also, countPane has to be exposed as at least a Pane since Region doesn’t expose getChildren() publicly.

Even worse, in any implementation of this, we still have button reconfiguring countLabel. Ideally, the only thing that configures countLabel should be countLabel itself, and the layout code that instantiates countLabel.

Finally, in any case where you have a reference to an object (Node or otherwise), that exposes the nature of its implementation, you have to check through the entire scope of that reference any time you contemplate making changes to that implementation. In the first imperative example, the scope was just waterCounter(){}, but in the last example the scope was the entire layout building class.

In this lastest example, if you did decide to change countLabel to something else, maybe that sprite ImageView or a Slider or a pie chart, you’d have to make sure that no other part of the layout class uses the implementation of countLabel. Maybe there’s some other Node that looks at the length of countLabel.getText() to determine some aspect of its layout.

The Presentation Model as a Layout Builder Field

In the first Reactive example, we had counter instantiated as a StringProperty variable reference local to waterCounter(){}. If we move button somewhere else, then we’ll need to expand the scope of counter to a field in the layout builder class. The code would look like this:

private val counter : IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(0)

.

.

.

fun waterCounter() : Region = VBox().apply {

children += Label("Glug...glug...glug...").apply {

visibleProperty().bind(counter.greaterThan(0))

managedProperty().bind(visibleProperty())

}

children += Label().apply {

textProperty().bind(counter.map{ "You've had $it glasses." })

}

}

.

.

.

fun someOtherPane() {

.

.

.

childern += Button("Add one").apply {

setOnClick { evt -> counter.value += 1 }

}

.

.

.

}

You can see that button remains completely ignorant of the existence of the counter Label.

There still is a dependency - there has to be. The counter Label is dependent on counter, and the Button knows about the nature of counter.

There are some things that make this a very different kind of coupling:

- The nature of

counteris very generic.

It is anIntegerProperty, which in the world ofPropertiesis no more specific than declaring a regular variable asInt. - Neither the counter

Label, nor theButtonis dependent on, even aware of the other. - Neither the counter

Label, nor theButtonis aware of, or dependent on the implementation the other. - Neither the counter

Label, nor theButtonis aware of the implementation ofcounter. - Any other

Nodein the layout can interact withcounterwithout impacting the implementation of either theButtonor the counterLabel.

There has to be some understanding of the meaning of counter within some scope. That scope might just be within the waterCounter(){} function, but it might be the entire layout builder class. It’s hard to imagine any degree of coupling that is less than this which is still functional.

In a very important way, though, we have compartmentalized and isolated that coupling. In this example, it’s counter, and we’ve essentially declared it the key the coupling point. Any Node that we create that interacts with counter needs to share that understanding of the meaning of counter, and behave accordingly. But it doesn’t have to understand how any other Nodes in the layout are interacting with counter.

Reactive Vs Imperative Design in a Framework

The goal of any framework, like MVC, MVP, MVVM or MVCI, is to reduce coupling. Specifically, they are designed to provide a clear separation between the business/application logic and the layout. This means that business logic works without any knowledge of the implementation of the layout, and the layout without any knowledge of the implementation of the business logic.

Let’s go back to our example…

Imperative Design With a Framework

Imagine that whatever change needs to happen to counter is determined to be “application logic”, so it can no longer reside in the layout. We’ll need to change the logic for the Button action. Let’s look at a first try at the imperative design approach first:

class layoutBuilder(private val counterChanger : (Int, (Int) -> Unit) -> Unit) {

.

.

.

fun someOtherPane() : Region = VBox().apply{

.

.

.

val counter : Int = 0

val glugLabel = Label("Glug...glug...glug...")

val button = Button("Add one")

button.setOnAction { evt ->

counterChanger.invoke(counter) { newCounter ->

counter = newCounter

countLabel.setText("You've had ${counter} glasses.")

if (counter > 0) {

countPane.getChildren().setAll(listOf(..., glugLabel, countLabel, ...))

} else {

countPane.getChildren().setAll(listOf(..., countLabel, ...))

}

}

}

children += button

}

}

Let’s look at that (Int, (Int) -> Unit) -> Unit first. This is the equivalent of the Java, BiConsumer<Integer, Consumer<Integer>>. It’s a functional element that accepts an Integer and another function that also accepts an Integer.

We don’t know what counterChanger does. Maybe it calls a website or some other external API, either of which would block the FXAT. So counterChanger might use Task to run the processing on a background thread. That means that we cannot just use (Int) -> Int, or Function<Integer, Integer> because we can’t wait for the answer to come back. Instead, we define a Consumer that will handle the answer when it comes back, and we send that off along with the current value of counter.

We also cannot assume that counter is going to increase through counterChanger. So we can’t just automatically add glugLabel when button is clicked. So we’ll need some logic to decide that.

You can see, though, that we still have a lot of coupling between button and the application logic that deals with counter. For instance, we know that it requires the current value of counter and nothing else. What if there were other factors involved? How about Spinner somewhere on the screen with a maximum value for counter? How about a CheckBox or ToggleButton that determined if the counter is incremented or decremented. Or something else that determined by how much? What if counterChanger also needs to reset that “how much” value back to 1 each time? All of this would change how button was implemented.

Let’s look at the next step towards solving this…

The Presentation Model in the Framework

Any of the frameworks - MVC, MVVM or MVCI - is going to have the Presentation Model represented somewhere. In MVC, it’s part of the “Model”, in MVVM it’s in the “ViewModel” and in MVCI it is the “Model” component. For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume that we’ve designed our framework implementation such that we can get the Presentation Model with a single method call, even if we are using MVC, or MVVM. That would be model.getPresentationModel() or viewModel.getPresentationModel().

Once we do that, we can assume that all of the components of the framework have easy access to the Presentation Model.

In this case, we would supply the Presentation Model to the layout builder class somehow, probably as a constructor parameter. But, because the Presentation Model is now shared, we don’t need to pass counter around any more. So we get this:

class layoutBuilder(private val presentationModel : PresentationModel,

private val counterChanger : (() -> Unit) -> Unit) {

.

.

.

fun someOtherPane() : Region = VBox().apply{

.

.

.

val glugLabel = Label("Glug...glug...glug...")

val button = Button("Add one")

button.setOnAction { evt ->

counterChanger.invoke {

countLabel.setText("You've had ${presentationModel.counter} glasses.")

if (presentationModel.counter > 0) {

countPane.getChildren().setAll(listOf(..., glugLabel, countLabel, ...))

} else {

countPane.getChildren().setAll(listOf(..., countLabel, ...))

}

}

}

children += button

}

}

Whatever counterChanger does, it’s impact is to modify counter inside presentationModel. Now, counterChanger is essentially a Consumer<Runnable>.

What does counterChanger do?

We don’t know the specifics, but there is an understanding that it will “change PresentationModel.counter”. Since it’s defined as a Consumer of a Runnable, it will execute that Runnable when it has finished updating PresentationModel.counter.

Let’s look at one of those, “What if?” questions from the end of the last section. The “How much?” question, and the idea of resetting it after each call to counterChanger. We’ll assume we have a Spinner<Int> somewhere in our layout, and it’s called howMuchSpinner. We’ll also add a value into our Presentation Model:

class PresentationModel {

var counter : Int = 0

var howMuch : Int = 1

}

Now, this is what our layout code looks like:

class layoutBuilder(private val presentationModel : PresentationModel,

private val counterChanger : (() -> Unit) -> Unit) {

.

.

.

fun someOtherPane() : Region = VBox().apply{

.

.

.

val glugLabel = Label("Glug...glug...glug...")

val button = Button("Add one")

button.setOnAction { evt ->

presentationModel.howMuch = howMuchSpinner.getValue()

counterChanger.invoke {

howMuchSpinner.setValue(presentationModel.howMuch)

countLabel.setText("You've had ${presentationModel.counter} glasses.")

if (presentationModel.counter > 0) {

countPane.getChildren().setAll(listOf(..., glugLabel, countLabel, ...))

} else {

countPane.getChildren().setAll(listOf(..., countLabel, ...))

}

}

}

children += button

}

}

Our button still doesn’t know exactly what counterChanger does. But it does need to know that its implementation requires howMuch and that it might change howMuch. It also needs to know that there is a Spinner called howMuchSpinner and that it needs to extract its value to update presentationModel before it invokes counterChanger.

Unfortunately, this is the end of the road for the Imperative approach. As long as the “State” of the GUI is stored inside the Nodes that make up the layout, there is no way to avoid building the logic to pick the pieces that you need out of those Nodes and updating the Presentation Model. And that, all by itself, demands that the layout logic is coupled to the implementation of the application logic.

But, you ask…What if you just always copy all of the Node data into the Presentation Model before any business logic call, and then copy it all back into the Nodes afterwards???

Well, if you’re going to do that, you might as well go with a Reactive design. Let’s look at how that would work:

Reactive Design Framework

We’ll start out by looking at the Presentation Model:

class PresentationModel {

val counter : IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(0)

val howMuch : IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(1)

}

Not that exciting, we’ve just changed the two fields over to IntegerProperty. Here’s our layout code:

class layoutBuilder(val presentationModel : PresentationModel,

val counterUpdater : () -> Unit) {

.

.

.

fun waterCounter() : Region = VBox().apply {

children += Label("Glug...glug...glug...").apply {

visibleProperty().bind(presentationModel.counter.greaterThan(0))

managedProperty().bind(visibleProperty())

}

children += Label().apply {

textProperty().bind(presentationModel.counter.map{ "You've had $it glasses." })

}

}

.

.

.

fun someOtherPane() {

.

.

.

children += Button("Add one").apply {

setOnClick { evt -> counterUpdater.invoke() }

}

.

.

.

}

}

Hmmmm…that doesn’t look different from the last Reactive version. We now have presentationModel passed in as constructor parameter and counter has been removed as a stand-alone field. References to counter have been changed to presentationModel.counter.

The only other change is that the Button event now calls the counterUpdater which, in this version, is the Kotlin equivalent to Runnable. We don’t need to pass anything to it, because everything is already synchronized with presentationModel, which the application logic has access to.

Note that the Button logic does nothing except invoke counterUpdater. It has no need to know about any other Nodes in the layout, nor does it have any need to know anything about the implementation of counterUpdater.

You’ll also note that I haven’t put in any code at all that deals with PresentationModel.howMuch. Presumably, there’s some kind of Node, or Nodes that synchronize with PresentationModel.howMuch, but they are not relevant to this discussion at all.

None of anything that we are discussing here is coupled to the implementation of PresentationModel.howMuch at all.

This Approach “Breaks” MVC

In Model-View-Controller there is a rule that says that the View is able to read the Presentation Model from the Model, but all changes to the Presentation Model must go through the Controller.

Right there, you cannot build a Reactive system with MVC. Because a Reactive system demands that the UI can update State, and this is explicitly forbidden in MVC. From a JavaFX perspective, this means that you cannot bidirectionally bind the Presentation Model to the layout Nodes, nor can you bind unidirectionally from a Node to the Presentation Model.

Should you care?

Probably not. But, if you do ignore this rule, and if you implement your Presentation Model as an enclosing object around your State Properties (even if it is still contained within the Model), then you’re 90% of the way from MVC to MVCI. And you might as well use MVCI - it’s better for this stuff anyways.

Application Logic in a Reactive Design

Let’s look at the other end of the framework, the application logic…

In MVC and MVVM, the application logic is in the Model. In MVCI the application logic is in the Interactor. MVC and MVCI are very similar in that application logic in both has access to the Presentation Model and can freely read and write from and to it. MVVM is different in that the Presentation Model is in the ViewModel and the Model doesn’t have open access to its elements. But that’s a different issue, and we can’t go into it here. So we’ll concentrate on MVCI, with the understanding that much of it applies to MVC as well.

Typically, in MVCI you would pass a reference to the Presentation Model to the Interactor as a constructor parameter so that the Interactor can access it freely. Let’s take a look at how we might implement our counterUpdater logic:

class Interactor(private val model : PresentationModel) {

fun updateCounter() : Int {

return someService(model.counter.value, model.howMuch.value)

}

fun newCounterValue(newVal : Int) {

model.counter.value = newVal

model.howMuch.value = 1

}

}

For context, this would be called from something like this, in the Controller:

fun updateCounter() {

val task : Task<Int> = object : Task() {

override fun call() : Int {

return interactor.updateCounter()

}

}

task.setOnSucceeded {evt -> interactor.newCounterValue(task.get())}

Thread(task).start()

}

If you are familiar with Task then you’ll see that Interactor.updateCounter() is called on the background thread, and Interactor.newCounterValue() is called from FXAT. This latter method, therefore, is allowed to update Properties bound to the Scene Graph. You should also notice, that the Interactor doesn’t have any explicit exposure to the threads involved, even though it is logically divided up into methods that can or cannot be run on the FXAT.

Exposing the Properties to the Interactor

You might have noticed that in our Interactor we have lines like this:

model.counter.value = newVal

Clearly, to do this, the Interactor has to be aware of the Property nature of model.counter or, in other words, the Interactor is dependent on the implementation of model.counter as a Property. Can we limit this?

You can. You can create an Interface that essentially has the getters and setters for the values of the Properties and then pass the Presentation Model to the Interactor as that Interface. Like this:

interface InteractorModel {

var counter: Int

var howMuch: Int

}

class PresentationModel : InteractorModel {

val counterProperty: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(0)

val howMuchProperty: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(0)

override var counter: Int

get() = counterProperty.get()

set(value) = counterProperty.set(value)

override var howMuch: Int

get() = howMuchProperty.get()

set(value) = howMuchProperty.set(value)

}

This looks a bit different in Kotlin. We’ve defined Int fields in the Interface, which is allowed in Kotlin. Then we’ve implemented these fields in PresentationModel such that they delegate their set() and get() methods to the get() and set() methods of the respective IntegerProperties. Now, we can do this:

class Interactor(private val model: InteractorModel) {

fun updateCounter() : Int {

return someService(model.counter, model.howMuch)

}

fun newCounterValue(newVal : Int) {

model.counter = newVal

model.howMuch= 1

}

}

And the Interactor can only interact with model.counter and model.howMuch as Int. The layout code, would now use bindings to model.counterProperty and model.howMuchProperty.

But what if you want to prevent the layout from changing model.counter? That actually seems like a reasonable requirement. We could expose model.counterProperty as ObservableIntegerValue, but the layout is still going to be able to update model.counter. How do we prevent that?

We just do the same thing as we did for the Interactor, except instead of exposing the getters and setters, expose only the Properties:

interface LayoutModel {

val counterProperty: ReadOnlyIntegerProperty

val howMuchProperty: IntegerProperty

}

class PresentationModel : InteractorModel, LayoutModel {

private val counterPropertyImpl: ReadOnlyIntegerWrapper = ReadOnlyIntegerWrapper(0)

override val counterProperty: ReadOnlyIntegerProperty = counterPropertyImpl.readOnlyProperty

override val howMuchProperty: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(0)

override var counter: Int

get() = counterPropertyImpl.get()

set(value) = counterPropertyImpl.set(value)

override var howMuch: Int

get() = howMuchProperty.get()

set(value) = howMuchProperty.set(value)

}

I’ve called the new Interface LayoutModel because ViewModel would get confusing. This Interface exposes howMuchProperty as IntegerProperty and counterProperty as ReadOnlyIntegerProperty. In the PresentationModel we now have a private IntegerProperty instantiated as ReadOnlyIntegerWrapper. Then we implement the Interface by instantiating counterProperty with counterPropertyImpl.getReadOnlyProperty().

Obviously, we pass PresentationModel to the layout builder class as LayoutModel and the layout builder only has acces to the fields as Properties, and counter is read-only.

The result is that the application logic treats the Presentation Model like set of normal Java types and objects, while the layout treats the same Presentation Model like a set of Observable objects that it can connect to the layout through Bindings and Listeners. In the end, the application logic performs, model.counter = newVal and the Label on the screen instantly changes.

Conclusion

I think that JavaFX gets missed as a Reactive GUI environment because it’s different from the other, commonly used systems like React.

I spent a bit of time looking through the results of a web search for “JavaFX reactive”, and it wasn’t very encouraging. Most of the results seemed to deal with integrating Reactive tools like RxJava with JavaFX. This is an interesting subject, but only tangential to Reactive GUI design. Those results that did deal with JavaFX as a Reactive GUI environment consisted of superficial surveys of a few Observable classes and not much else.

It’s almost disappointing that you can build a working application using a declarative/imperative approach to GUI design with JavaFX, because that’s as far as most people seem to get. Add FXML into the mix, and Reactive design gets pushed even further into the background. I don’t think I’ve ever seen an example of an FXML based Reactive JavaFX application. They’re probably out there, but nobody seems to be talking about it.

It’s a shame, because, like so many things with JavaFX, once you know how to do it properly it becomes so much easier than doing it the “wrong” way. Reactive GUI applications in JavaFX are really that much simpler than declarative/imperative designs, have so much less coupling - all over the application - and are easier to maintain and enhance.

When you integrate a Reactive design into MVCI (which is what it is designed for) you end up with a Presentation Model that is treated as a collection of Observables for binding at the layout end of the application, and treated as a collection of generic Java/Kotlin types and objects at the application logic. That Presentation Model becomes a conduit for each end of the application - View and Application Logic - to communicate with each other in the manner that makes the most sense to them, without knowing about each other. That allows them to interact without becoming coupled.