Introduction

Recently, I posted an article titled, Should You Use FXML?. In that article, I stated that I felt that well written and organized code would always be easier to maintain than any corresponding FXML/FXML Controller would be. I did not emphasize this, as the article was intended to be a discussion about the merits and costs of using FXML more than as a “is this better than this?”, exploration.

In the article, I included a sample of a large (462 line) FXML file that I grabbed somewhat randomly from GitHub. Some readers expressed the opinion that the FXML was “bad”, and that they write better FXML by hand. Some expressed concern that I had cherry-picked bad FXML to use as an example, while others seemed upset at the idea of randomly picking FXML as an example.

I wasn’t sure about how to respond to these comments because I realized that the frame of reference between myself and these commentors was just too different. It really didn’t matter to me if the FXML example that I picked was good, bad or average.

It didn’t matter because I understand that the way that I write layout code is astronomically better than FXML can ever be.

But I couldn’t say that. Who would believe me? What makes me think my coding is so much better?

This article is my attempt to explain my position. I’m going to take that example FXML and its FXML Controller code (and other stuff it turns out it needs to work), and re-write it as purely coded layout in Kotlin.

My hope is that you can look at the original FXML and code, and then look at my version, and you will see the potential for writing your layouts by hand.

And this is not about me or my coding skill. There’s nothing in my version that anyone reading this article couldn’t do themselves, or learn to do themselves.

Approach

Generally speaking, the goal is to reproduce the layout as close as possible to the original, so that it becomes clear just how much easier it is to understand and maintain a hand coded layout. However, there are secondary considerations that need to be taken into account:

- Improving the Layout

-

I was torn about this at first. Eventually, I decided that there might be aspects of layout design that are adversely affected by using SceneBuilder to create the FXML file. It might be obvious, when hand-coding, that the same look and feel can be achieved through a better design. I have chosen to implement these improvements as these are generally problems that wouldn’t arise coding the layout by hand.

This shows that the impact of hand-coding goes beyond being simply a matter of clarity and maintainability, but also affects the application design.

- Implementing a Framework

-

The orginal design, like most FXML implementations, has too much functionality in the FXML Controller. This is probably through the misplaced belief that the FXML Controller acts as an MVC Controller. In order to understand how a hand-coded layout is better in this respect, a MVCI framework has been applied. This results in the creation of a Presentation Model, and moving all of the application logic found in the FXML Controller into the Interactor.

- Changing to a Reactive Design

-

It’s clear to me that JavaFX is intended to be used as a Reactive framework, and that it just works better that way. Systems built with a Reactive approach are simpler and cleaner, and easier to understand.

- Threading and the FXAT

-

The FXML Controller doesn’t have any code that attempts to perform potentially blocking (like file access) operations off the FXAT. There’s no point in creating bad code for conversion, so I’ve organized the code such that thread handling is performed as it should be.

- WidgetsFX

-

Since this is intended as an example of how a real application would be put together, I have chosen to use my own WidgetsFX library to implement many of the builders, extension functions and helper classes that I would ordinarily use to build layouts. I’m not including any of that code here, but you can easily tell what it would do.

I also freely admit that I worked with the WidgetsFX project open, and that I added new functionality to it as required. This is the way that I would ordinarily work, and it’s also how the WidgetsFX library grows organically over time.

- Styling

-

I’ve chosen to move any styling in the FXML or the FXML Controller into an external style sheet. Then I’m not going to create that style sheet because…why bother. The result is that the screens in my project, while having an identical effective layout, don’t look like the originals…but that’s not the point.

Kotlin

I’m writing this all in Kotlin for two reasons. Firstly, I find Java painful and unsatisfying to code with after several years of writing mostly Kotlin. Secondly, Kotlin just makes it so much easier to write clear, easy to understand layout code.

I think that, even if you don’t fully understand the syntax, the Kotlin code is easy enough to understand for most Java programmers. Take a look at this:

VBox(10.0).apply {

padding = Insets(25.0)

.

.

.

children += intSpinnerOf(1, 50, "standard-spinner", model.connectorThickness.asObject())

.setStep(1)

.bindDisable(model.selectedDistance.isNull)

.withInitialDelay(Duration.millis(500.0))

.withRepeatDelay(Duration.millis(500.0))

}

}

You don’t really need to know the details of how the extension function .apply{} works to understand that the code inside the {} configures the VBox. You can see that the padding is set to 25px, even though you don’t understand that Kotlin allows you to refer directly to values of fields that have getters and setters and that it will still call those getters and setters. Then, children += is clearly using the += operator on a List to do the equivalent of getChildren().add().

It’s also clear that setStep(), bindDisable(), withInitialDelay() and withRepeatDelay() are all configuration methods for the Spinner. Since they are chained, all of these methods are designed as decorators.

It’s obviously not clear what the parameters of intSpinnerOf() are, but Intellij displays what the parameter names are. So when you really are working with this code, there is no question what the parameters mean.

For purposes of this article, pretty much any Java programmer can look at this snippet of code and understand that it defines a VBox with a particular padding and that it contains a Spinner<Integer> that has been configured in a particular way and bound to some Property in the Model. That’s probably enough to get the point.

The Original Version

You can find this project on GitHub here.

I was concerned that the project might be deleted or change beyond recognition over time, so I placed a snapshot of the FXML file, the FXML Controller and a few supporting files in this article. I’m not going to include all the code in this article itself, because it’s just going to be too big.

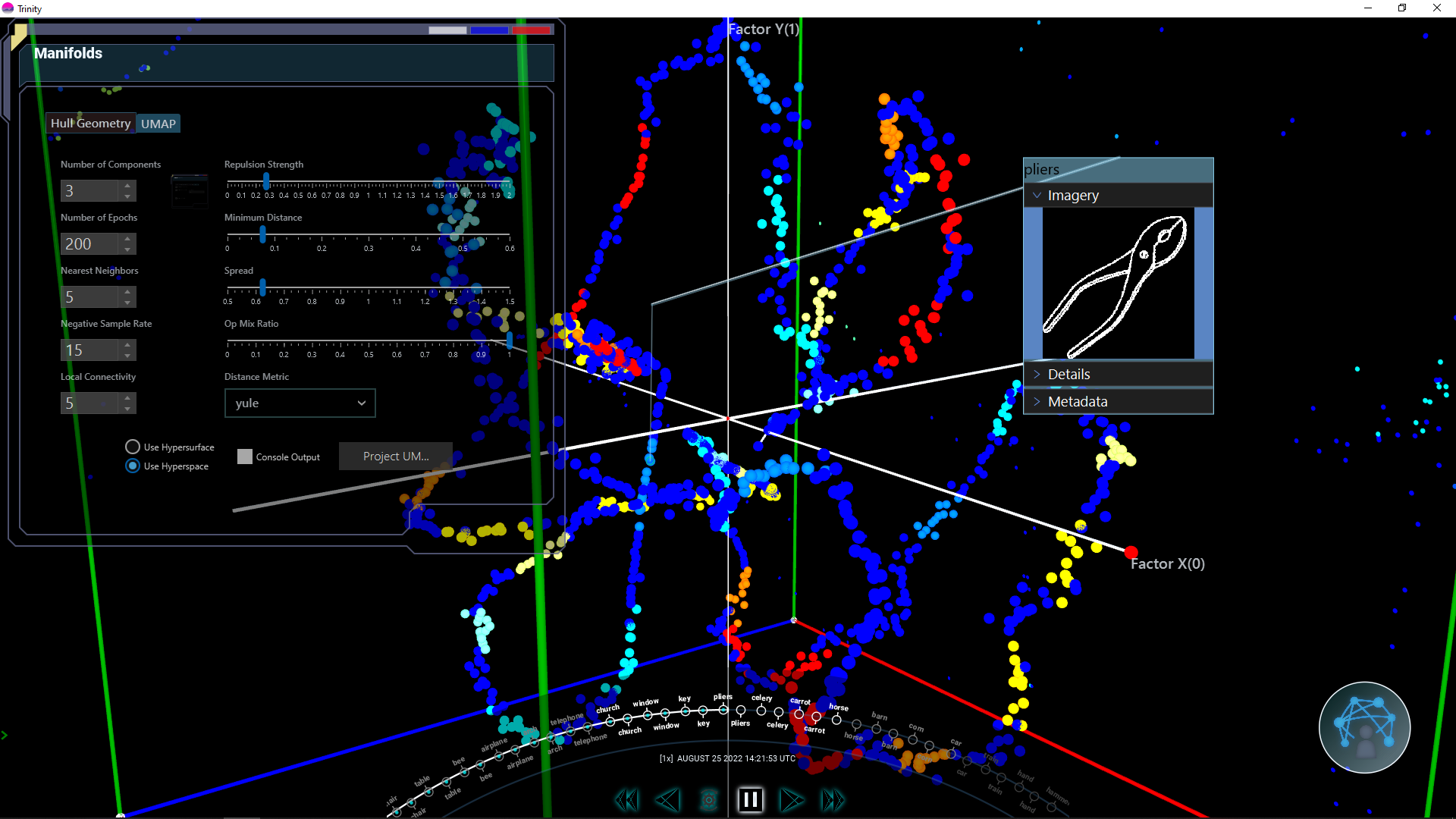

When the program is running, the screen looks like this, although this version from the read.me page appears to be out of date and doesn’t quite match what the code does:

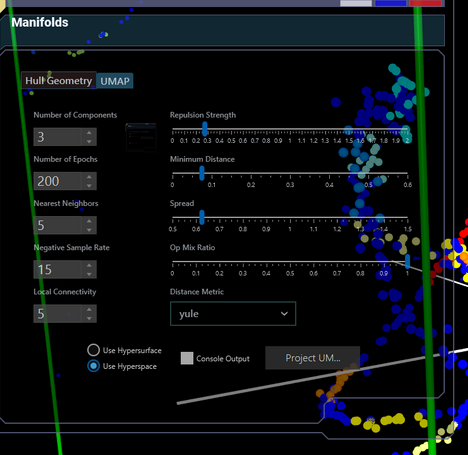

The code we are working on is the control panel in the upper left corner, so here it is close-up:

Unfortunately, we don’t have screen shots of all of the Tabs in the control panel, but you can get a sense of the design from this.

There’s obviously some pretty strong styling going on here, it looks like maybe they used AtlantaFX? I didn’t go looking, and I’m not going to make any attempt to duplicate it. There is zero code or FXML that applies any of this styling, so I’m deeming it “out of scope”.

Notes While Performing the Conversion

As I went through the process of performing the conversion, I made a point of taking some notes about issues that I encountered and ideas that occured to me…

This Was Probably Generated From SceneBuilder

I came across this in the FXML file:

<HBox alignment="CENTER" spacing="10.0" GridPane.columnSpan="2147483647" GridPane.rowIndex="8">

I cannot see any human entering “2147483647” as a columnSpan value. So this is either generated from SceneBuilder, or copypasta from some section that was generated by SceneBuilder.

Why does this matter? If the contention is that FXML is clear and easy to read, and yet we can blame most of the strange structures that make this file difficult to understand on SceneBuilder - then that’s an issue.

The Design is Difficult to Understand

It’s monolithic. 462 lines of FXML, and you need to scan all of it to understand that it’s basically just 4 Tabs in a TabPane. The GridPanes were a particular chore, as the components were not organized in the FXML file at all, just jumbled up willy-nilly and difficult to locate.

All in all, I spent more time trying to understand the FXML and FXML Controller than I did writing my own version.

“Bad” FXML Doesn’t Appear Be More Verbose

It has become clear that you wouldn’t write FXML like this by hand. It’s just too jumbled up for that, and probably crosses into the realm of “bad” FXML. However, there really isn’t anything in its jumbled-upness that makes it longer or more verbose. As a matter of fact, there are things about it - like the lack of “row” or “column” specifications for GridPane elements in row or column 0 - that make it a bit less verbose.

The inescapable truth seems to be that if you are going to create a layout of this complexity, then you are going to need 450+ lines of FXML to do it. No matter how good your FXML writing skills are.

Dealing With FileChooser

In most of my programming, I don’t use FileChooser much at all, but this project and this screen do. So I had to grapple with the question of “Where does it go in the MVCI structure?”. It can be argued that FileChooser is a GUI element, and therefore belongs to the View, and that’s were I initially placed it. But then I ended up with references to File objects, and that caused me to look closer at this approach.

First off, File is most distinctly not a front end class. It seemed worrying to have this data type handled by the GUI code.

Secondly, the File had to be passed back to the Interactor somehow, because it’s the Interactor that was going to use it. This made it really clear to me that there was an issue. Why does the View get to know anything about the back-end structure. Furthermore, the View doesn’t actually use the File object, it just passes it back to the Controller.

Now, what happens if the storage is changed from JSON files to a database? Or the application is changed to facilitate sharing designs between different users by email? Would that mean that you would have to change the View in order to make this change?

For sure, that FileChooser would need to change. Maybe it becomes a Dialog that allows for load and save to a database, or to select an email with attachments (or to send an email). But there’s no reason that you should have to change the View for that.

In the end, I moved the FileChooser calls into the Controller, which is where I think they really belong. It’s now integrated with the thread handling and invocation of Interactor methods. The File object is no longer tramp data passing from the View through the Controller to the Interactor.

Unused? Elements

In the Tab labeled “PCA” there are two RadioButtons, “Use Hyperspace” and “Use Hypersurface” that do NOT have their isSelected values used in any code in the FXML Controller.

However, the ToggleGroup to which they belong, pcahyperSourceGroup is NOT private to the FXML Controller. So it is possible that some other class with a reference to this FXML Controller is accessing this ToggleGroup, getting a reference to the RadioButton that is selected, and (Gasp!!!) checking it’s text value to find out which RadioButton it is.

Don’t try this at home.

Needless to say, I’m not sure if these RadioButtons do or do not do anything - and that should be immediately apparent from reading the code. I’ve connected these RadioButtons to some elements in the Model that are clearly named as some kind of “dummy” value.

It may be that I grabbed the code in the middle of development and it just wasn’t yet complete. There were several new releases of this project between writing and publishing this article. On the other hand, this may just be something that somehow got lost and forgotten in the hundreds of lines of code here.

Connecting to the Rest of the Application

When you look at the screen snaps on the project Read.me page, it’s clear that this screen is supposed to be a control/input screen for a real-time display elsewhere in the application. As such, there needs to be a way to communicate with the rest of the application in real-time.

We see that the original code implements this communication through EventHandlers, like this:

scene.addEventHandler(ManifoldEvent.DISTANCE_CONNECTOR_SELECTED, e -> { }

for incoming Events, and this:

scene.getRoot().fireEvent(new ManifoldEvent(ManifoldEvent.DISTANCE_CONNECTOR_WIDTH, item.getDistance()));

for outgoing Events.

This is probably one of the most insidious issues that can occur when you forego implementing a proper framework. The code you are writing is Event centric, so then everything is now an Event. Even when it really isn’t. I’ll discuss this more when we look at the new design.

Changes to the Design

It was clear when doing the conversion that there were “issues” with the original design. Furthermore, it was clear that it would not make sense to leave these issues unaddressed when performing the conversion.

Issues With the Original Design

Most of these issues, as far as I can tell, are a direct result of utilizing FXML in the way that most of the tutorials, including those from Oracle, tell you to. From what I can see, these issues build on each other. Let’s take a look at them:

There is no Framework

The original implementation assumed that the FXML file was the “View” and the FXML Controller was the “Controller” and the domain objects collectively comprised the “Model”. The results is that virtually all of the code resides in the FXML Controller and it does way, way too much while doing none of it well.

This is, in my opinion, a big problem with the design of this application, and this clearly shows how the automatic “separation of concerns” claimed for FXML is just a myth. There is no separation here, you have application logic, file handling and communication with other parts of the application muddled up with the configuration of individual Nodes. Within the layout itself, you have extensive coupling of Nodes all over the layout.

There is no Presentation Model

All of the data is stored in the screen Nodes, and there is no external data storage outside of the value Properties of the Nodes themselves. This means that all of the data must to be scraped out of the Nodes when it’s needed, which, in turn, means that all of the Node variables have to be globally scoped so that their data is available when required. Globally scoping those variables is a massive source of coupling within the FXML Controller.

Of course, the design of FXML requires that all of the Nodes from the layout that are going to be accessed from the FXML Controller are instantiated as fields in the FXML Controller, which means that they are globally scoped. This makes it harder to see the benefits of attempting to limit the scope of these variables by implementing a Presentation Model.

Finally, without a Presentation Model, it’s much more difficult to share the data with the application logic. This is obscured in this application by including the application logic inside the FXML Controller.

It is an “Action” Based Design

Without a Presentation Model to act as a data representation of the “State” of the GUI, it is very difficult to create a Reactive design. Instead of linking GUI elements together through the Presentation Model, they are directly referenced by other GUI elements.

The effect of this is that the application becames Node-centric, instead of data centric, and this shift, in turn, leads to an “Action” based design.

Using Events to Communicate Between Screens

The elements in this screen are used to control the manner in which data in other windows and screens is displayed. This means that this screen needs to communicate somehow with other windows and screens that are external to this layout. The programmers have decided to use JavaFX Events to do this. Consider this snippet of code:

connectorThicknessSpinner.valueProperty().addListener(e -> {

DistanceListItem item = distancesListView.getSelectionModel().getSelectedItem();

if (null != item) {

Integer width = (Integer) connectorThicknessSpinner.getValue();

item.getDistance().setWidth(width);

scene.getRoot().fireEvent(

new ManifoldEvent(ManifoldEvent.DISTANCE_CONNECTOR_WIDTH, item.getDistance()));

}

});

Here we have a Spinner configured such that every time its value changes a Listener is triggered and that Listener will eventually fire a ManifoldEvent of a certain type, in this case ManifoldEvent.DISTANCE_CONNECTOR_WIDTH type.

Presumably, some external EventHandler is configured to respond to this ManifoldEvent and do something.

On the surface, this seems like a reasonable approach: The programmers needed a reliable messaging facility to communicate between components, and the JavaFX Event system seems to fit the bill. But there are some problems with this:

-

Sequencing can be a problem.

EventsinvokeEventHandlerswhich are submitted to the FXAT. If a system is very active, it’s possible that there’s a lot of items in the FXAT queue, and they may have changed the environment in which theEventHandlerwill run. You cannot control this. -

It deals in domain objects. That call to

item.getDistance()returns aDistancewhich is a domain object. -

Related to the previous item, the domain objects are stored in singleton

ListsinDistanceandManifold. This leads to timing issues where domain objects might exist in the singleton lists but not in theListViewsyet. There is code that defends against this and generates errors when this happens. -

Delivery is not guaranteed. There’s nothing to say that some screen element couldn’t filter an

Eventbefore it gets to its intended target. This might be hard to debug. Essentially, theEventsystem is global and couples everything that uses it. -

It’s not clear who the recipient is.

Eventsare, by definition, broadcast entities. To find out how thisEventis handled, you’ll have to search through the entire application to see which classes have anEventHandlerfor theManifoldEvent.DISTANCE_CONNECTOR_WIDTHsubtype.

Personally, I think that Events and EventHandlers are best used for very localized things. This would mean adding an EventHandler onto the Button that generates the Event (like a click ActionEvent). Using the JavaFX Event system as a general communication bus feels like a “code smell” to me.

The ListViews

This is the only part of the design which is objectively “wrong” from a technical JavaFX respect.

There are two classes for each ListView, let’s look at the one for manifolds. We have the class ManifoldListItem which extends VBox, and the class Manifold which we should probably consider to be a “Domain Object”. Every ManifoldListItem contains a reference to a Manifold.

The biggest problem is that the ListView is defined as ListView<ManifoldListItem> and then has no ListCell defined anywhere. This violates one of the principal rules of ListView and TableView: Do NOT put Nodes as the items.

I don’t even know how this works. Honestly, this was the one thing that took me the closest to actually downloading the whole project and building it to see if it actually works.

The Manifold class has a static HashMap field that stores all of the Manifolds that have been created - essentially a singleton that can be accessed through the whole application. Whenever a new Manifold is created, there should also be an ManifoldEvent fired that should trigger an EventHandler added to the Scene. That EventHandlercreates a new ManifoldListItem and adds it to the ListView.

If the manifold HashMap is cleared, there should be an accompanying ManifoldEvent fired which trigger a different EventHandler set on the Scene.

There are three ColorPickers outside the ListView that display colours associated with the item selected in the ListView. There is code that updates the value in these ColorPickers when an ManifoldEvent indicating that a new Manifold has been selected. Also, when the value in the Spinners is changed, it fires a ManifoldEvent that presumably gets handled externally and updates the Manifold.

If all of this seems very confusing and roundabout, that’s because it is. This is one of those cases where doing it wrong is so, so much more complicated than doing it right. We’ll see how this works in the next section.

The New Design

The new version uses MVCI as a framework to implement a Reactive design. There is a Presentation Model composed of Observable data classes which are then bound (mostly bi-directionally) to the value Properties of the screen Nodes. This means that the layout elements are instantiated, configured, bound to the Presentation Model and then added to the layout and forgotten. There is no need to ever reference them again, as everything important about them has been bound to Properties in the Presentation Model.

There is no need to “scrape” data out of the GUI Nodes.

All of the application logic has been moved out of the layout code and into the Interactor. The Interactor is suprisingly small, because much of complexity of communication with the external screen has now been eliminated through shared data.

There is a SharedModel class which contains JavaFX Observable objects that are supplied by whatever element of the overall application contains this screen.

The Controller, as usual, handles instantiation, threading and connectivity to the rest of the application’s GUI.

The ListViews

This was the biggest architectural change to the design. The Manifold and Distance domain objects were transformed into Presentation Objects and all of the singleton related stuff was removed. Now they are simple JavaFX Observable POJO`s.

The ListViews were changed to have custom ListCells that mirrored the structure in the ManifoldListItem and DistanceListItem classes. These ListCells contain interactive Nodes like TextField and CheckBox who’s values are bi-directionally bound to the corresponding Properties in the item currently loaded into the ListCell.

To handle the values inside Manifold and Distance that are updated from outside the ListView, the Model has two Properties:

val selectedDistance: ObjectProperty<Distance> = SimpleObjectProperty()

val selectedManifold: ObjectProperty<Manifold> = SimpleObjectProperty()

These need to be synchronized with the current selection in the ListViews. Ordinarily you could do this:

infix fun <T : Any> ListView<T>.bindSelection(boundProperty: ObjectProperty<T>): ListView<T> = apply {

boundProperty.bind(selectionModel.selectedItemProperty())

}

But there’s a twist here…

The selected item needs to be synchronized with an external selection of those objects from some other part of the application. This needs to be in both directions. That external component needs to be able to select these objects, and react to changes in the selection from these ListViews. Ordinarily, you’d just make the bind bi-directional, but there’s an issue there:

final ReadOnlyObjectProperty<T> selectedItem

Oh no! The selectedItem property in SelectionModel is read-only! The only way to change the value programmatically is to call SelectionModel.selectItem(). This means we’ll have to use subscriptions to handle the changes:

infix fun <T : Any> ListView<T>.connectSelection(connectedProperty: ObjectProperty<T>): ListView<T> = apply {

selectionModel.selectedItemProperty().subscribe { newItem -> connectedProperty.value = newItem }

connectedProperty.subscribe { newItem -> selectionModel.select(newItem) }

}

If you think about it, you’ll realize that triggering the subscription on one Property due to a change in the other won’t cause an infinite loop because the result of that subscription will bring the two values in sync and won’t trigger the second subscription.

You can now see that this screen doesn’t even need to know about the domain objects Manifold and Distance any more. These elements - if they exist at all - are created somewhere else and then presumably used to create Manifold and Distance presentation data objects.

“Drag ‘n Drop” File Import

Right near the top of the FXML Controller, there is some code that initialized the “root” of the Scene as the destination for a drag ‘n drop operation to load a configuration file. The idea being, I assume, that you can just drag a file from a file manager application into this layout and it will load it in if it is, in fact, a configuration file.

I wrestled with the idea of putting the EventHandlers for drag and drop into the layout itself, but then realized that I’d have to supply an action handler for this to the ViewBuilder from the Controller. The end result would be that I would have a File object floating around in my layout code, even if indirectly. This part bothered me.

I came to the conclusion that the drag and drop didn’t have anything to do with the layout as a layout. This would be different if there was a box in the layout that said “Drop Files Here” and only that box would respond to the drag and drop operation. In this situation, we don’t have anything like this, and the entire layout can just be considered as a Node (in this case a Region, but we only care about it as a subclass of Node) and dealt with from the outside.

This means that it makes sense to add the drag and drop handling as a decorator onto the layout directly from the Controller. Now, we don’t have to pass any handlers over to the ViewBuilder, since it isn’t involved. In fact, neither the ViewBuilder or the layout itself has any knowledge that it is a drag and drop destination.

In the Controller, the getView() method now looks like this:

fun getView(): Region = viewBuilder.build() asFileDrop { loadUmap(it[0]) }

It’s worth looking at the WidgetsFX implementation of this, since it is a great example of how the boilerplate can be stripped out of your application code:

infix fun <T : Node> T.asFileDrop(handler: (List<File>) -> Unit): T = apply {

addEventHandler(DragEvent.DRAG_OVER) { event ->

event.acceptTransferModes(TransferMode.COPY)

}

addEventHandler(DragEvent.DRAG_DROPPED) { event ->

with (event.dragboard) {

if (hasFiles()) {

handler.invoke(files)

}

}

}

}

Everything in here is boilerplate and every time you implement this you would need those 11 lines of code. But now it just becomes asFileDrop {do something}.

The Large Number of Action Handlers

There’s a lot of Buttons in this screen, and all of them trigger some kind of action within the application logic.

How do we provide all these action handlers to the View?

The first thing to understand is that the Reactive nature of the new design means that all of the data that might be relevant to any action is already represented in the Model and is always fully up to date.

This means that no action handler ever has to supply data from the GUI. The only information that is required is which Button was clicked.

The few actions that need to open FileChoosers need to pass the Window (Stage) that triggered it as FileChooser needs this to work. I chose to implement these such that the Button would grab this element as part of its EventHandler that runs at click-time. These actions do need to pass that element back to the action handler.

Two Enums were created, one for the FileChooser operations, called FileOperation and the other for all the other operations, called GeneralOperation. “Operation” seems less likely to get confused with “Action”. Naming things is hard! The action handler is a Consumer<GeneralOperation>, or in Kotlin notation (GeneralOperation) -> Unit, and each Button will call the handler’s invoke(GeneralOperation) method, passing the appropriate GeneralOperation value to it.

It is the Controller’s job to define this action handler and provide it to the ViewBuilder. Unless there is some thread handling required in the nature of any of these actions, the Controller has no business getting involved in the execution of these actions, which is the domain of the Interactor. This action handler is essential a “dispatch routine”, which invokes an appropriate Interactor method for each operation type via the Kotlin version of switch:

private fun generalOperation(operation: GeneralOperation) {

when (operation) {

GeneralOperation.BUILD_CLUSTER -> interactor.buildCluster()

GeneralOperation.GENERATE -> interactor.generate()

GeneralOperation.CLEAR_ALL -> interactor.clearAll()

GeneralOperation.EXPORT_ALL -> interactor.exportAll()

GeneralOperation.CLEAR_DISTANCES -> interactor.clearDistances()

GeneralOperation.PROJECT -> interactor.project()

GeneralOperation.EXPORT_MATRIX -> interactor.exportMatrix()

GeneralOperation.SAVE_PROJECTIONS -> interactor.saveProjections()

GeneralOperation.RUN_PCA -> interactor.runPca()

}

}

For all practical purposes, most of these operations do not have any real application logic associated with them that resides inside of this MVCI framework. They instead are triggering actions elsewhere in the application. We’ll look at that next…

Connecting to the Rest of the Application

There is a SharedElements class which contains JavaFX Observable objects that are supplied by whatever element of the overall application contains this screen. This is the main source of coupling to the rest of the application’s GUI. Sharing these data elements has the magic effect of making all the Event firing and EventHandlers in the original version totally redundant.

Let’s look at how this works…

In a situation where this screen is part of a larger application, whatever GUI element of that application that “owns” this screen would pass a SharedElements object to the Controller via its constructor. This SharedElements object is then passed to the Model via its constructor. At this point, the Controller’s involvement with the SharedElements is done.

SharedElements is a set of Properties which are defined externally. These are used to instantiate the Property fields in the Model. Like this:

val showWireFrame: BooleanProperty = sharedElements.showWireFrame

val showControlPoints: BooleanProperty = sharedElements.showControlPoints

It’s important to note that since these elements are incorporated into the Model, just like any other elements, the fact that these are Properties defined externally is never exposed to the View or the Interactor. Any changes to the manner in which these are implemented, connected or related to the Properties in the Model are never going to ripple through to be changes in the View or the Interactor.

In a similar manner an object of the class SharedFunctions is passed to the constructor of the Controller, which calls it externalFunctions. This is, in turn, passed to the Interactor via its constructor. At this point, the Controller’s involvement with SharedFunctions is complete.

The Interactor then invokes these external functions as part of the application logic related to performing various actions related to Button clicks in the View.

On the surface this seem very round-about but it actually isolates the coupling nicely. The View has a Button that triggers an EventHandler. That EventHandler invokes an action Consumer that is defined by the Controller. That Consumer invokes an corresponding method in the Interactor which, in turn, invokes a Runnable provided to the Interactor from outside the MVCI construct through the Controller.

Information about what these pieces do is available on a strict “need to know” basis throughout the framework. There is an Enum which is shared between the Controller and the ViewBuilder that defines what operations can be invoked from the View, but the View has no idea what those operaitons do. The Controller knows how to invoke corresponding methods in the Interactor, but has no idea what those methods do. The Interactor knows which external operations to call, but it has no idea what they do. Finally, the Controller passes the list external operation handlers to the Interactor, but doesn’t know what they are.

Counting Lines of Code/FXML

I’m not generally a fan of counting code, but it can be an indicator of the complexity, readability and maintainability of a system.

Let’s look at the original:

| Element | Lines |

|---|---|

| FXML | 462 |

| FXML Controller | 752 |

| ManifoldListItem | 76 |

| DistanceListItem | 55 |

| Manifold | 130 |

| Distance | 190 |

| Total | 1665 |

Now, let’s look at the hand-coded version:

| Element | Lines |

|---|---|

| Model | 60 |

| Controller | 48 |

| Interactor | 80 |

| ViewBuilder | 230 |

| ManifoldListCell | 21 |

| DistanceListCell | 24 |

| SharedElements | 12 |

| SharedFunctions | 12 |

| Total | 487 |

The hand-coded version is less than 1/3 the amount of code in the original version - although I’m not sure how compare FXML to lines of code. In any event, the entire hand-coded version is only slightly larger than the FXML file itself.

Is it Easier to Understand?

I always feel that the most common use case for someone performing maintenance or enhancement to a layout is going to start out by looking at the actual running screen. Then they are going to want to get a feel for how some specific section of the layout is designed.

In this case, we have a bunch of Tabs and the programmer is probably going to want to drill down into the code for a specific Tab.

Let’s take a look at the top of the layout code, were the root elements are defined:

override fun build(): Region = TabPane(

createUmapTab(),

createPcaTab(),

createDistancesTab(),

createHullTab()

) withClosingPolicy TabPane.TabClosingPolicy.UNAVAILABLE

private fun createPcaTab() = Tab("PCA") withContents (VBox(10.0, pcaGridPane(), pcaButtonBox()) padWith 25.0)

private fun createUmapTab() = Tab("UMAP") withContents VBox(10.0)

.padWith(25.0)

.addChild(umapGridPane())

.addChild(umapDistanceThresholdBox())

.addChild(umapControlBox())

private fun createDistancesTab() = Tab("Distances") withContents HBox(10.0, distanceLeft(), distanceRight())

private fun createHullTab() = Tab("Hull Geometry") withContents BorderPane()

.withTop(hullTop())

.withLeft(manifoldPropertyBox())

.withCenter(manifoldBox())

We can see right away that the entirety of the layout is a single TabPane with 4 Tabs that cannot be closed. We have a short builder method for each Tab with an name that mirrors the title of each Tab. No matter which Tab you are interested in you can quickly find it, without even having to scroll down through the code.

We can quickly get an idea about the structure of the contents of these Tabs. Two are VBoxes, one is an HBox and the other is a BorderPane. There are builders for every element contained in these Regions in the Tabs, and we can click-through on them to get to them.

You can also see here that all of the configuration elements such setPadding() have been implemented as extension decorator functions that have also been implemented as “infix” functions. This means that they can be used without the . and () and can, in some cases, increase readability.

In some cases, it looks cleaner if the dot notation is used instead. This allows the decorators to be stacked vertically when they start to add up. However, when the composition is trivial, then the infix notation keeps the coding trivial. Compare the “PCA” Tab to the “UMAP” Tab.

I’ve tried to avoid naming the builders with positional names whenever possible. However, I really don’t know what this application does, so it was hard to guess at good names for some builders. I gave up with the builder for the layout in BorderPane.top in the “Hull” Tab, and I just called it hullTop().

I find that GridPanes are always clumsy to deal with, no matter what, and the row/column locations never jump out at you when scanning the code. However, you can organize the code to make it easier to find things. I tried this with the “UMAP” GridPane:

private fun umapGridPane() = GridPane().apply {

columnConstraints += ColumnConstraints(10.0, 200.0, 288.0).apply { hgrow = Priority.SOMETIMES }

columnConstraints += ColumnConstraints(10.0, 200.0, 380.0).apply { hgrow = Priority.SOMETIMES }

addRowConstraints(10, stdRowConst)

umapSpinnerColumn()

umapSliderColumn()

}

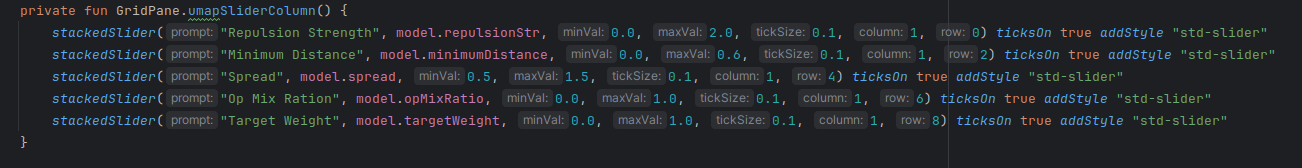

private fun GridPane.umapSliderColumn() {

stackedSlider("Repulsion Strength", model.repulsionStr, 0.0, 2.0, 0.1, 1, 0) ticksOn true addStyle "std-slider"

stackedSlider("Minimum Distance", model.minimumDistance, 0.0, 0.6, 0.1, 1, 2) ticksOn true addStyle "std-slider"

stackedSlider("Spread", model.spread, 0.5, 1.5, 0.1, 1, 4) ticksOn true addStyle "std-slider"

stackedSlider("Op Mix Ration", model.opMixRatio, 0.0, 1.0, 0.1, 1, 6) ticksOn true addStyle "std-slider"

stackedSlider("Target Weight", model.targetWeight, 0.0, 1.0, 0.1, 1, 8) ticksOn true addStyle "std-slider"

}

private fun GridPane.umapSpinnerColumn() {

stackedIntSpinner("Number of Components", model.numberOfComponents, 2, 5, 1, 0, 0) addStyle "std-spinner"

stackedIntSpinner("Number of Epochs", model.numberOfEpochs, 25, 500, 25, 0, 2) addStyle "std-spinner"

stackedIntSpinner("Nearest Neighbours", model.nearestNeighbour, 5, 500, 5, 0, 4) addStyle "std-spinner"

stackedIntSpinner("Negative Sample Rate", model.negativeSampleRate, 1, 250, 1, 0, 6) addStyle "std-spinner"

stackedIntSpinner("Local Connectivity", model.localConnectivity, 1, 250, 1, 0, 8) addStyle "std-spinner"

}

This GridPane has two columns, the one on the right has a bunch of Sliders with their Labels, and the one on the left has Spinners and their Labels. In both columns, the Label sits on the row above its corresponding input Control. It’s now easy to see the structure of the GridPane at a glance. In contrast, translating these GridPanes from the FXML took more time than any other part because you couldn’t just look at it quickly and understand the structure.

It’s not clear when you see the code in these articles that the IDE that I use (Intellij IDEA) provides a lot of on-screen information that’s not seen here. For instance, this is what I see with umapSliderColumn():

From here it is clear what all of those parameters do.

One further thing, which I think contributes greatly to the “easier to understand” aspect of this discussion. You can see that ALL of the parameters related to these input Controls are included here in these 10 method calls. There’s no need to go running off somewhere else see how one of the Spinners is configured. Each one is also bi-directionally bound to a Property field in the Model, so there’s no need to mess about with initial values either - as that is handled in the Model or the Interactor.

The New Code

Oh, wow! That’s a lot of discussion and preamble, and not a lot of coding. Let’s take a look at the completed redesign.

The ViewBuilder

This is the bulk of the code…

class FromFxmlViewBuilder(

private val model: FromFxmlModel,

private val fileOp: (Window, FileOperation) -> Unit,

private val genOp: (GeneralOperation) -> Unit

) :

Builder<Region> {

private val stdRowConst = RowConstraints().apply {

minHeight = 10.0

prefHeight = 30.0

vgrow = Priority.NEVER

}

override fun build(): Region = TabPane(createUmapTab(), createPcaTab(), createDistancesTab(), createHullTab())

.withClosingPolicy(TabPane.TabClosingPolicy.UNAVAILABLE)

private fun createPcaTab() = Tab("PCA") withContents (VBox(10.0, pcaGridPane(), pcaButtonBox()) padWith 25.0)

private fun createUmapTab() = Tab("UMAP")

.withContents(VBox(10.0, umapGridPane(), umapDistanceThresholdBox(), umapControlBox()).padWith(25.0))

private fun createDistancesTab() = Tab("Distances") withContents HBox(10.0, distanceLeft(), distanceRight())

private fun createHullTab() = Tab("Hull Geometry") withContents BorderPane()

.withTop(hullTop())

.withLeft(manifoldPropertyBox())

.withCenter(manifoldBox())

private fun umapGridPane() = GridPane().apply {

columnConstraints += ColumnConstraints(10.0, 200.0, 288.0).apply { hgrow = Priority.SOMETIMES }

columnConstraints += ColumnConstraints(10.0, 200.0, 380.0).apply { hgrow = Priority.SOMETIMES }

addRowConstraints(10, stdRowConst)

umapSpinnerColumn()

umapSliderColumn()

}

private fun GridPane.umapSliderColumn() {

stackedSlider("Repulsion Strength", model.repulsionStr, 0.0, 2.0, 0.1, 1, 0) ticksOn true addStyle "std-slider"

stackedSlider("Minimum Distance", model.minimumDistance, 0.0, 0.6, 0.1, 1, 2) ticksOn true addStyle "std-slider"

stackedSlider("Spread", model.spread, 0.5, 1.5, 0.1, 1, 4) ticksOn true addStyle "std-slider"

stackedSlider("Op Mix Ration", model.opMixRatio, 0.0, 1.0, 0.1, 1, 6) ticksOn true addStyle "std-slider"

stackedSlider("Target Weight", model.targetWeight, 0.0, 1.0, 0.1, 1, 8) ticksOn true addStyle "std-slider"

}

private fun GridPane.umapSpinnerColumn() {

stackedIntSpinner("Number of Components", model.numberOfComponents, 2, 5, 1, 0, 0) addStyle "std-spinner"

stackedIntSpinner("Number of Epochs", model.numberOfEpochs, 25, 500, 25, 0, 2) addStyle "std-spinner"

stackedIntSpinner("Nearest Neighbours", model.nearestNeighbour, 5, 500, 5, 0, 4) addStyle "std-spinner"

stackedIntSpinner("Negative Sample Rate", model.negativeSampleRate, 1, 250, 1, 0, 6) addStyle "std-spinner"

stackedIntSpinner("Local Connectivity", model.localConnectivity, 1, 250, 1, 0, 8) addStyle "std-spinner"

}

private fun umapDistanceThresholdBox() = HBox(10.0).apply {

alignment = Pos.TOP_CENTER

children += VBox(10.0, promptOf("Distance Metric"), ChoiceBox(generateDefaultMetrics()).firstSelected())

children += VBox(

10.0,

promptOf("Threshold (if applicable)"),

doubleSpinnerOf(0.01, 1.0, "standard-spinner", model.threshold.asObject()).setStep(0.01)

)

}

private fun umapControlBox() = HBox(15.0, umapConfigButtonBox(), umapHyperBox(), umapRunExportButtonBox())

private fun umapConfigButtonBox() = VBox(10.0).apply {

children += buttonOf("Load New Config") { println("Hello") } addStyle "standard-button"

children += buttonOf("Save Current Config") { fileOp.invoke(this.scene.window, FileOperation.UMAP_SAVE) }

.addStyle("standard-button")

}

private fun umapHyperBox() = VBox(10.0).apply {

with(ToggleGroup()) {

addChild(RadioButton("Use Hypersurface") inToggleGroup this)

addChild(RadioButton("Use Hyperspace") inToggleGroup this setSelected true)

}

addChild(CheckBox("Progress Output"))

}

private fun umapRunExportButtonBox() = VBox(

10.0,

buttonOf("Run UMAP") { genOp.invoke(GeneralOperation.PROJECT) } addStyle "standard-button",

buttonOf("Export TMatrix") { genOp.invoke(GeneralOperation.EXPORT_MATRIX) } addStyle "standard-button",

buttonOf("Export Projections") { genOp.invoke(GeneralOperation.SAVE_PROJECTIONS) } addStyle "standard-button"

)

private fun pcaButtonBox() = HBox(

15.0,

buttonOf("Project Data") { genOp.invoke(GeneralOperation.RUN_PCA) } addStyle "standard-button",

buttonOf("Export Projections") { genOp.invoke(GeneralOperation.SAVE_PROJECTIONS) } addStyle "standard-button"

) alignTo Pos.CENTER

private fun pcaGridPane() = GridPane().apply {

columnConstraints += ColumnConstraints(10.0, 200.0, 288.0).apply { hgrow = Priority.SOMETIMES }

columnConstraints += ColumnConstraints(10.0, 200.0, 380.0).apply { hgrow = Priority.SOMETIMES }

addRowConstraints(10, stdRowConst)

pcaLeftColumn()

pcaRightColumn()

}

private fun GridPane.pcaRightColumn() {

add(promptOf("Component Analysis Type"), 1, 0)

with(ToggleGroup()) {

add(radioButtonOf("PCA (EigenValue)", model.analysisMethodPca, this, "std-radio"), 1, 1)

add(

radioButtonOf("Singular Value Decomposition", model.analysisMethodSvd, this, "std-radio"), 1, 2

)

}

add(promptOf("Input Data Source"), 1, 3)

with(ToggleGroup()) {

add(radioButtonOf("Use Hypersurface", model.dummyBoolean1, this, "std-radio"), 1, 4)

add(radioButtonOf("Use Hyperspace", model.dummyBoolean2, this, "std-radio"), 1, 5)

}

}

private fun GridPane.pcaLeftColumn() {

stackedIntSpinner("Number of Components", model.numberOfPcaComponents, 2, 5, 1, 0, 0) addStyle "std-spinner"

add(checkBoxOf("Enabled Ranged Fitting (Experimental)", model.rangeFitting, "std-checkbox"), 0, 2)

stackedIntSpinner("Fit Start Index", model.fitStartIndex, 0, 500, 5, 0, 3)

.bindDisable(model.rangeFitting.not()) addStyle "std-spinner"

stackedIntSpinner("Fit End Index", model.fitEndIndex, 5, 2000, 5, 0, 5)

.bindDisable(model.rangeFitting.not()) addStyle "std-spinner"

stackedIntSpinner("Output Scaling Factor", model.pcaScalingFactor, 1, 1000, 0, 10, 7) addStyle "std-spinner"

}

private fun distanceLeft() = VBox(10.0).apply {

padding = Insets(25.0)

children += h3Of("Distance Metric")

children += dataOf(StringExpression.stringExpression(model.selectedDistance.flatMap { it.metric }

.orElse("Select Distance")))

with(ToggleGroup()) {

children += radioButtonOf("Point to Point", model.pointToPoint, this, "std-radio")

children += radioButtonOf("Point to Group", model.pointToGroup, this, "std-radio")

}

children += h3Of("Connector Thickness")

children += intSpinnerOf(1, 50, "standard-spinner", model.connectorThickness.asObject())

.setStep(1)

.bindDisable(model.selectedDistance.isNull)

.withInitialDelay(Duration.millis(500.0))

.withRepeatDelay(Duration.millis(500.0))

children += promptOf("Connector Colour")

children += ColorPicker().apply {

promptText = "Change the colour of the 3D connector"

valueProperty().bindBidirectional(model.connectorColour)

bindDisable(model.selectedDistance.isNull)

}

}

private fun distanceRight() = VBox(10.0).apply {

children += HBox(

10.0,

h3Of("Collected Distances"),

buttonOf("Clear All") { genOp.invoke(GeneralOperation.CLEAR_DISTANCES) }) alignTo Pos.CENTER

children += (ListView<Distance>() withItems model.distanceList withCellFactory Callback { DistanceListCell() } connectSelection model.selectedDistance).apply {

model.externallySelectedDistance.subscribe { newValue ->

this.selectionModel.select(newValue)

}

}

}

private fun manifoldPropertyBox(): Region = VBox(10.0).apply {

children += promptOf("Selected Manifold Properties")

children += titledPaneOf("Material") {

TwoColumnGridPane().addColorPickerRow("Diffuse Colour", model.manifoldDiffuseColour, "std-color-picker")

.addColorPickerRow("Wire Mesh Colour", model.manifoldWireMeshColour, "std-color-picker")

.addColorPickerRow("Specular Colour", model.manifoldSpecularColour, "std-color-picker")

} withCollapsable false

children += meshViewPane()

}

private fun meshViewPane() = titledPaneOf("MeshView") {

VBox(5.0).apply {

children += radioButtonHBox(

"Cull Face",

listOf(

Pair("Front", model.frontCullFace),

Pair("Back", model.backCullFace),

Pair("None", model.noneCullFace)

), 5.0, "std-radio-button"

)

children += radioButtonHBox(

"Draw Mode",

listOf(Pair("Fill", model.fillDrawMode), Pair("Lines", model.linesDrawMode)),

5.0,

"std-radio-button"

)

children += HBox(

10.0,

checkBoxOf("Show Wire Frame", model.showWireFrame, "std-checkbox"),

checkBoxOf("Show Control Points", model.showControlPoints, "std-checkbox")

)

}

} withCollapsable false

private fun hullTop(): Region = HBox(10.0).apply {

padWith(10.0)

children += hullTopGridPane()

children += VBox(

20.0,

buttonOf("Generate") { genOp.invoke(GeneralOperation.GENERATE) },

buttonOf("Cluster Tools") { genOp.invoke(GeneralOperation.BUILD_CLUSTER) }

)

}

private fun hullTopGridPane() = TwoColumnGridPane()

.addRadioButtonHBoxRow(

"Point Set",

listOf(Pair("Visible", model.useVisible), Pair("All", model.useAll)),

5.0,

"std-radio-button"

)

.addRow("Distance Tolerance") {

HBox(

10.0,

checkBoxOf("Auto", model.toleranceAuto, "std-checkbox"),

doubleSpinnerOf(0.1, 1.0, "std-spinner", model.toleranceManual.asObject()).setStep(0.1)

.bindDisable(model.toleranceAuto)

)

}

.addChoiceBoxRow("Find by Label", model.factorLabelList, model.selectedFactorLabel, "std-choice-box", true)

private fun manifoldBox(): Region = VBox(5.0).apply {

children += h3Of("Generated Manifolds")

children += HBox(20.0).apply {

children += buttonOf("Clear All") { genOp.invoke(GeneralOperation.CLEAR_ALL) }

children += buttonOf("Export All") { genOp.invoke(GeneralOperation.EXPORT_ALL) }

}

children += ListView<Manifold>() withItems model.manifoldList withCellFactory Callback { ManifoldListCell() } connectSelection model.selectedManifold

}

}

One of the first things you should notice is that except for the container classes, none of the Nodes are instantiated directly using their constructors. All of them are instantiated via builder methods of some sort, and those builders are generic enough that they are included in WidgetsFX.

This points out one of the biggest problems with the standard JavaFX library - a lack of constructors that allow a parameter for value binding.

For those layout classes, I’ve used three standard techniques for populating them:

- Providing the children as constructor parameters.

- Using

getChildren().add()viachildren +=inside.apply{}. - Using the extension function

Pane.addChild()

In practice, I found that Pane.addChild() outside of apply{} was no better than just including the children as constructor parameters. It’s also not clear if Pane.addChild() is any clearer than children += inside of an apply{} block.

There are a fair number of GridPanes in this layout. GridPane is fine when there is a strict need to keep columns and rows locked together in some fashion, but that is rarely the case in this layout. Particularly in the UMAP GridPane, where the Labels and Controls are stacked in successive rows, with the Spinner inputs in one column and the Slider inputs in another column. Is there really any need to keep the elements aligned by row?

While I don’t think I would use a GridPane in this case (two VBoxes in an HBox would be simpler), I did create the extension functions GridPane.stackedSlider, and GridPane.stackedIntSpinner to get the repeated elements out of the GridPane configuration.

For the infix decorator functions, I’ve used them as infix when only one or two functions were called, and they would fit onto a single line. When more functions were called, it was more clear to use the regular notation and stack them one per line in the code.

I am aware that the infix notation and the extension functions are difficult to get used to at first. A couple of years ago, I would have shied away from using them and simply put all of this functionality into apply{} blocks. Today, I find the apply{} approach to be overly verbose in many cases.

The net result of the extension functions and builder methods is to strip virtually all of the configuration details and boilerplate out of the layout code leaving something where you can understand the effect of that configuration without obscuring the layout itself.

I do feel that this:

private fun manifoldPropertyBox(): Region = VBox(10.0).apply {

children += promptOf("Selected Manifold Properties")

children += titledPaneOf("Material") {

TwoColumnGridPane()

.addColorPickerRow("Diffuse Colour", model.manifoldDiffuseColour, "std-color-picker")

.addColorPickerRow("Wire Mesh Colour", model.manifoldWireMeshColour, "std-color-picker")

.addColorPickerRow("Specular Colour", model.manifoldSpecularColour, "std-color-picker")

} withCollapsable false

children += meshViewPane()

}

is far easier to understand than:

<VBox spacing="10.0" BorderPane.alignment="CENTER">

<children>

<Label text="Selected Manifold Properties"/>

<TitledPane collapsible="false" text="Material" VBox.vgrow="ALWAYS">

<content>

<VBox spacing="5.0">

<children>

<HBox alignment="CENTER_LEFT" spacing="10.0">

<children>

<Label prefWidth="125.0" text="Diffuse Color"/>

<ColorPicker fx:id="manifoldDiffuseColorPicker" editable="true" prefHeight="50.0"

prefWidth="150.0"/>

</children>

</HBox>

<HBox alignment="CENTER_LEFT" spacing="10.0">

<children>

<Label prefWidth="125.0" text="Wire Mesh Color"/>

<ColorPicker fx:id="manifoldWireMeshColorPicker" editable="true" prefHeight="50.0"

prefWidth="150.0"/>

</children>

</HBox>

<HBox alignment="CENTER_LEFT" spacing="10.0">

<children>

<Label prefWidth="125.0" text="Specular Color"/>

<ColorPicker fx:id="manifoldSpecularColorPicker" editable="true" prefHeight="50.0"

prefWidth="150.0"/>

</children>

</HBox>

</children>

</VBox>

</content>

</TitledPane>

.

.

.

</VBox>

Especially when you take into consideration the ~40 lines of code that configure these ColorPickers in the FXML Controller. In the Kotlin code, these 3 lines completely configue the ColorPickers and they are never referenced again…anywhere.

ListView Cells

The original design didn’t properly handle the two ListViews properly at all. These two classes provide Cell layouts that emulate what the original code did:

class DistanceListCell : ListCell<Distance>() {

private val label = Label()

private val distanceValueLabel = Label()

private val visibleCB = CheckBox("Visible")

private val layout = HBox(5.0, visibleCB, label, distanceValueLabel)

override fun updateItem(newItem: Distance?, isEmpty: Boolean) {

item?.let {

label.textProperty().unbind()

distanceValueLabel.textProperty().unbind()

visibleCB.selectedProperty().unbindBidirectional(it.visible)

}

super.updateItem(newItem, isEmpty)

graphic = null

text = null

if (!isEmpty) {

newItem?.let {

label.textProperty().bind(it.label)

visibleCB.selectedProperty().bindBidirectional(it.visible)

distanceValueLabel.textProperty().bind(Bindings.concat(it.metric, ": ", it.distance.asString()))

graphic = layout

}

}

}

}

class ManifoldListCell : ListCell<Manifold>() {

private val label = TextField().apply {

focusedProperty().subscribe { newVal ->

if (newVal) listView.selectionModel.select(item)

}

}

private val visibleCB = CheckBox("Visible").apply {

focusedProperty().subscribe { newVal ->

if (newVal) listView.selectionModel.select(item)

}

}

private val layout = HBox(5.0, visibleCB, label)

override fun updateItem(newItem: Manifold?, isEmpty: Boolean) {

item?.let {

label.textProperty().unbindBidirectional(it.label)

visibleCB.selectedProperty().unbindBidirectional(it.visible)

}

super.updateItem(newItem, isEmpty)

graphic = null

text = null

if (!isEmpty) {

newItem?.let {

label.textProperty().bindBidirectional(it.label)

visibleCB.selectedProperty().bindBidirectional(it.visible)

graphic = layout

}

}

}

}

The Controller

Here’s the code for the Controller:

class FromFxmlController(sharedElements: SharedElements, externalFunctions: SharedFunctions) {

private val model = FromFxmlModel(sharedElements)

private val viewBuilder = FromFxmlViewBuilder(model, this::dataOperation, this::generalOperation)

private val interactor = FromFxmlInteractor(model, externalFunctions)

fun getView(): Region = viewBuilder.build() asFileDrop {

runStandardVoidTask({ interactor.loadUmap(it[0]) }, { interactor.completeLoadUmap() })

}

private fun dataOperation(window: Window, operation: FileOperation) {

when (operation) {

FileOperation.UMAP_SAVE -> saveUmap(window)

FileOperation.UMAP_LOAD -> chooseAndloadUmap(window)

}

}

private fun generalOperation(operation: GeneralOperation) {

when (operation) {

GeneralOperation.BUILD_CLUSTER -> interactor.buildCluster()

GeneralOperation.GENERATE -> interactor.generate()

GeneralOperation.CLEAR_ALL -> interactor.clearAll()

GeneralOperation.EXPORT_ALL -> interactor.exportAll()

GeneralOperation.CLEAR_DISTANCES -> interactor.clearDistances()

GeneralOperation.PROJECT -> interactor.project()

GeneralOperation.EXPORT_MATRIX -> interactor.exportMatrix()

GeneralOperation.SAVE_PROJECTIONS -> interactor.saveProjections()

GeneralOperation.RUN_PCA -> interactor.runPca()

}

}

private fun saveUmap(window: Window) {

FileChooser().apply {

title = "Choose UMAP Config file output.."

initialFileName = "UmapConfig.json"

initialDirectory = model.latestDir.value ?: File(".")

}.showSaveDialog(window)?.let {

runStandardVoidTask({ interactor.saveUmap(it) }, { interactor.completeSaveUmap() })

}

}

private fun chooseAndloadUmap(window: Window) {

FileChooser().apply {

title = "Choose UMAP Config to load..."

initialDirectory = model.latestDir.value ?: File(".")

}.showOpenDialog(window)?.let {

runStandardVoidTask({ interactor.loadUmap(it) }, { interactor.completeLoadUmap() })

}

}

}

This is pretty simple. There’s the standard instantiation of the other elements, and then two dispacth methods to handle actions triggered by the View. Additionally, we have two methods to invoke FileChooser as part of a workflow to handle the file operations.

The Model

Here is the Model code:

class FromFxmlModel(sharedElements: SharedElements) {

val externallySelectedDistance: ObjectProperty<Distance> = sharedElements.selectedDistance

val externallySelectedManifold: ObjectProperty<Manifold> = sharedElements.selectedManifold

val toleranceManual: DoubleProperty = sharedElements.toleranceManual

val numberOfComponents: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(3)

val numberOfEpochs: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(200)

val nearestNeighbour: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(15)

val negativeSampleRate: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(5)

val localConnectivity: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(1)

val repulsionStr: DoubleProperty = SimpleDoubleProperty(1.0)

val spread: DoubleProperty = SimpleDoubleProperty(1.0)

val minimumDistance: DoubleProperty = SimpleDoubleProperty(0.1)

val opMixRatio: DoubleProperty = SimpleDoubleProperty(0.5)

val targetWeight: DoubleProperty = SimpleDoubleProperty(0.5)

val threshold: DoubleProperty = SimpleDoubleProperty(0.1)

val numberOfPcaComponents: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty()

val dummyBoolean1: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val dummyBoolean2: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val pcaScalingFactor: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(100)

val fitStartIndex: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(0)

val fitEndIndex: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(50)

val rangeFitting: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val dummyBoolean4: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val analysisMethodSvd: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val analysisMethodPca: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val connectorThickness: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(17)

val connectorColour: ObjectProperty<Color> = SimpleObjectProperty()

val pointToPoint: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val pointToGroup: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val latestDir: ObjectProperty<File?> = SimpleObjectProperty()

val manifoldDiffuseColour: ObjectProperty<Color> = SimpleObjectProperty(Color.CYAN)

val manifoldWireMeshColour: ObjectProperty<Color> = SimpleObjectProperty(Color.BLACK)

val manifoldSpecularColour: ObjectProperty<Color> = SimpleObjectProperty(Color.BLACK)

val frontCullFace: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val backCullFace: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val noneCullFace: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val fillDrawMode: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val linesDrawMode: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val showWireFrame: BooleanProperty = sharedElements.showWireFrame

val showControlPoints: BooleanProperty = sharedElements.showControlPoints

val useAll: BooleanProperty = sharedElements.useAll

val useVisible: BooleanProperty = sharedElements.useVisible

val toleranceAuto: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val distanceList: ObservableList<Distance> = sharedElements.distanceList

val manifoldList: ObservableList<Manifold> = sharedElements.manifoldList

val factorLabelList: ObservableList<String> = FXCollections.observableArrayList()

val selectedFactorLabel = sharedElements.selectedFactorLabel

val selectedDistance: ObjectProperty<Distance> = SimpleObjectProperty()

val selectedManifold: ObjectProperty<Manifold> = SimpleObjectProperty()

init {

sharedElements.manifoldCullFace.bind(Bindings.createObjectBinding({

if (frontCullFace.value) return@createObjectBinding CullFace.FRONT

if (backCullFace.value) return@createObjectBinding CullFace.BACK

return@createObjectBinding CullFace.NONE

}, frontCullFace, backCullFace, noneCullFace))

}

}

This is just a POJO of JavaFX Observable classes. The fields that are tied to the external application are instantiated as references to the corresponding field in SharedElements. SharedElements.manifoldCullFace corresponds to whichever of three BooleanProperties is true, and is bound that way.

SharedElements is not exposed to any other component of the MVCI construct, and looks like this:

class SharedElements {

val distanceList: ObservableList<Distance> = FXCollections.observableArrayList()

val manifoldList: ObservableList<Manifold> = FXCollections.observableArrayList()

val selectedDistance: ObjectProperty<Distance> = SimpleObjectProperty()

val selectedManifold: ObjectProperty<Manifold> = SimpleObjectProperty()

val toleranceManual: DoubleProperty = SimpleDoubleProperty()

val useAll: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val useVisible: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val manifoldCullFace: ObjectProperty<CullFace> = SimpleObjectProperty()

val showWireFrame: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val showControlPoints: BooleanProperty = SimpleBooleanProperty(false)

val selectedFactorLabel: StringProperty = SimpleStringProperty()

}

In truth, I got fed up searching through all of the ManifoldEvents to find out what data was being passed back and forth to other parts of the application. So I’m sure that this SharedElements object is missing quite a few elements. There’s enough here to make the point, though, and without the rest of the application it doesn’t make any difference for this demonstration.

The Interactor

The last MVCI component is the Interactor:

class FromFxmlInteractor(private val model: FromFxmlModel, private val externalFunctions: SharedFunctions) {

private var umapDto: UmapDto? = null

init {

createDummyData()

model.selectedDistance.subscribe { oldValue, newValue ->

oldValue?.let {

model.connectorThickness.unbindBidirectional(it.width)

model.connectorColour.unbindBidirectional(it.colour)

}

newValue?.let {

model.connectorThickness.bindBidirectional(it.width)

model.connectorColour.bindBidirectional(it.colour)

}

model.externallySelectedDistance.value = newValue

}

model.selectedManifold.subscribe { oldValue, newValue ->

oldValue?.let {

model.manifoldDiffuseColour.unbindBidirectional(it.diffuseColour)

model.manifoldSpecularColour.unbindBidirectional(it.specularColour)

model.manifoldWireMeshColour.unbindBidirectional(it.wireframeColour)

}

newValue?.let {

model.manifoldDiffuseColour.bindBidirectional(it.diffuseColour)

model.manifoldSpecularColour.bindBidirectional(it.specularColour)

model.manifoldWireMeshColour.bindBidirectional(it.wireframeColour)

}

model.externallySelectedManifold.value = newValue

}

}

private fun createDummyData() {

model.distanceList.add(Distance("Label 1", "Millimetres", 17.0, 8, Color.GREEN))

model.distanceList.add(Distance("Label 2", "Nanometres", 22.0, 1, Color.CYAN))

model.distanceList.add(Distance("Label 3", "Millimetres", 8.0, 10, Color.AZURE))

model.distanceList.add(Distance("Label 4", "Millimetres", 45.0, 3, Color.RED))

model.manifoldList.add(Manifold("Label 1"))

model.manifoldList.add(Manifold("Label 2"))

model.manifoldList.add(Manifold("Label 3"))

model.manifoldList.add(Manifold("Label 4"))

}

fun buildCluster() {

externalFunctions.buildCluster.invoke()

}

fun generate() {

externalFunctions.generate.invoke()

}

fun clearAll() {

externalFunctions.clearAll.invoke()

}

fun exportAll() {

externalFunctions.exportAll.invoke()

}

fun clearDistances() {

externalFunctions.clearDistances.invoke()

}

fun project() {

externalFunctions.project.invoke()

}

fun exportMatrix() {

externalFunctions.exportMatrix.invoke()

}

fun saveProjections() {

externalFunctions.saveProjections.invoke()

}

fun runPca() {

externalFunctions.runPCA.invoke()

}

fun saveUmap(file: File) {

model.latestDir.value = file

}

fun completeSaveUmap() {}

fun loadUmap(file: File) {

println("Hey! Loading a file")

}

fun completeLoadUmap() {}

}

The init{} section is much like a constructor, and here it creates all of the relationships between elements of the Model that would be considered “business/application logic”. In this case it is mostly dealing with the relationships between the actively selected Manifold or Distance and some of the other properties.

The rest of this feels much more like a skeleton than it really is. The file handling methods are just placeholders, as they would need to connect to a service of some sort which would do the heavy lifting.

All of the other methods, however, are pretty much in their final form. They just need to invoke the functional elements provide by ExternalFunctions, which looks like this:

class SharedFunctions {

val buildCluster: () -> Unit = {}

val generate: () -> Unit = {}

val clearAll: () -> Unit = {}

val exportAll: () -> Unit = {}

val clearDistances: () -> Unit = {}

val project: () -> Unit = {}

val exportMatrix: () -> Unit = {}

val saveProjections: () -> Unit = {}

val runPCA: () -> Unit = {}

}

These would ordinarily be defined in some other part of the application which is actually going to do the work. These functions completely replace all of the ManifoldEvent firings in the original FXML Controller.

Conclusion

I’m not going to pretend that I understand what this project does, but my impression is that it involves really complicated and sophisticated analysis of some kind of AI processing. But when you look at this screen it’s really just a bunch of Controls and Buttons and Lists that manipulate some data and trigger some actions.

The original design leaks the complexity of the entire application into what should be a simple screen. You cannot change a data value without knowing how that will impact the rest of the application.

I need to stress that the code that I’ve published here runs as a stand-alone application. It doesn’t connect to anything, but it works and can be integrated into the rest of the application simply by providing the shared data and functions in the Controller constructor.

Clearly, a lot more was done here than just replace the FXML with code, although it’s fairly clear that the layout code is much simpler than the FXML plus FXML Controller from the original.

The Layout

I deliberately put this project aside for a while so that I could come back to get a more objective sense of how easy it is to read and understand the 230 lines of layout code.

One thing that was immediately clear to me when I came back to it was that none of these Tabs have anything to do with each other except that they cohabit in the same TabPane. As such, they could all be defined in their own builders, and each one would, therefore, be a little bit easier to understand since they wouldn’t be encumbered with the code from the other Tabs.

Furthermore, each of these Tabs could have their own, independent, MVCI structure associated with them. There could be a “master” MVCI structure associated with the TabPane itself, and its Controller could handle instantiation of all of the other MVCI structures. This would make each of the 4 separate MVCI constructs extremely simple and easy to understand.

Even if a Button on one Tab required the external function it invoked to use data from another Tab this wouldn't matter because the Button actions aren't transferring any data - that's already handled by the shared data elements.

Using a Framework

I simply cannot imagine building anything like this without implementing a framework of some kind.

One of the things that became glaringly apparent after the conversion was that this screen, aside from some file handling, doesn’t actually do anything itself. You can see this just from looking at the Interactor. It doesn’t have much code that actually does anything. It just dispatches actions off to some other part of the application.

Certainly, if you had written the application, or if you were very familiar with the entire application, you’d know that this screen didn’t actually do anything. But this is absolutely not clear from a casual glance at the original code.

Reactive vs Imperative Design

A much as I think the coded layout is a win compared to FXML, I think that this exercise really illustrates the wonderful simplicity that comes from implementing a Reactive design. There are literally hundreds of lines of code in the FXML Controller that just vanish away when a Reactive design is implemented.

Using a Reactive design also makes it trivial to connect to external elements of the application through a shared data model. This approach also greatly simplifies the understanding of the coupling between this screen and those external elements as it is all defined inside that single object.

Coupling

Coupling in this new design is extremely controlled, and easy to understand.

The Model is the main source of coupling, but it also isolates as well. There’s no way for anything outside of the View to know if a Boolean value in the Model is presented to the user via a RadioButton, a ToggleButton, a CheckBox or some custom Control. But, no matter how it’s handled in the View, the Interactor can always simply deal with the Boolean value that it is bound to.

In a similar manner, the SharedElements is the main source of both coupling and isolation between this screen and the rest of the application.

Coupling is usually the single biggest source of unecessary complexity in any application. Controlling coupling is the best way to improve code quality.

I simply cannot stress this too much. Virtually every good (or “clean”) coding technique, is designed to control and eliminate coupling as much possible. Looking at this “Trinity” project, excessive coupling is everywhere and it makes everything much more complicated than it needs to be. I’ve tried to limit coupling as much as possible in my version, and I think it is reflected in the lack of complexity.

The Kotlin

It’s really clear from this example just how much Kotlin lets you extract the boilerplate and verbosity out of the layout code. The infix extension decorator functions mean that you never have to instantiate any element of the layout as a variable. In most cases the instantiation, configuration, binding and addition to the layout of the Nodes is done in a single line.

Maybe (probably?) you don’t want to learn Kotlin to do this. In Java, I think you’d have to create classic builders with the configuration elements included as decorators. But you could do a lot of this stuff that way.

What I will say is that if you are looking for a tool to make layout creation and maintenance easier, you’ll get a lot more mileage out of learning Kotlin than you will by mastering SceneBuilder and FXML.