Introduction

When my team and I began Java programming back in 2011, we went through the same experience that I’ve gone through with just about every new technology that I’ve learned on the job over my career. That is to say, we went from “Hello World”, to trying to write the most complicated stuff you could think of in just a few weeks.

In this case, while the team was composed of programmers who were experts in the technologies that we had been using to date, we had no Java experience and were attempting to extend a multi-user enterprise legacy application and deliver new functionality to our users as soon as possible. Back then, we were using Swing and learning how to deal with brand new (to us) Java concepts at the same time that we were trying to understand how to design GUI screens and integrate it with a complex legacy system.

This meant, of course, that our early work hellaciously bad. Really, really bad. We were fumbling around trying to learn how to work with a single-threaded GUI, while trying to figure out how to connect to our legacy database and handle performance issues related to that. We had heard a little bit about MVP, and we tried to implement its ideas without really understanding why we should even be doing that.

But we learned, and we got better.

What If the Legacy System Goes Away?

While there was lots, and lots, and lots of stuff we did wrong, we did get one thing right. We decided right up front to confront the question of, “What happens if the legacy system goes away?”. Really, the question was about how our custom work could continue to function if the technology underlying the legacy system was to be replaced.

We dealt with this by thinking of our applications in slices. At one end was the user, and the code that interacted with the user. At the extreme other end was the legacy system and our Java code that directly interacted with the legacy system. We divided that legacy-facing end into two pieces, one slice we called the “Brokers” and the other we called the “DAO’s”. The idea was that the DAO classes would know about the files in the legacy system, and would know about the subroutines or the API routines that we had built in the legacy system. The Brokers would talk to the DAO’s and get data back, and the assemble them into “Business Objects” that we could pass on to the layers of the applicaitons that were closer to the users.

We still had an issue with the nature of the data that came back from the DAO’s. It was a proprietary structure in Java that was provided by the database vendor, and it handled the quirks of the database that was being used. We messed around for a while trying to come up with something more generic, but our Java skills at the time just weren’t up to the task. Finally, we just accepted that if we replaced the legacy system, then we’d have to scrap the whole DAO layer and do substantial work to the Broker layer to handle the data coming in a different format.

In the end, after more than a decade, the legacy system was replaced. However, the people in the corner offices with the two and three letter job titles decided, without consulting with the programmers, to toss everything - including our Java applications - and start from scratch with a new system. They never realized how much effort we had put in to build something that could still work even if the legacy system was replaced.

But it wasn’t a total loss. The divisions that we built in our architecture allowed us to deploy the Broker and DAO layers as separate libraries, and resuse them in over and over again for a large number of desktop applications. This saved us a huge amount of effort and helped to simplify our system design. And, believe me, we needed all the help we could get in that department.

Throughout all of this we continued to move to a better and better understanding of how to build GUI applications with JavaFX. While we were saddled with a lot of early mistakes that we had to live with for a long time, we were able to make it all work because we dealt with that one question, “What happens if the legacy application goes away?”, right at the beginning.

That structure is what this article is about. It’s a look at what is probably the most common approach to handling external systems and integrating them with GUI applications. There’s no code in this article, it’s all about explaining what the parts do, and why they are connected together this way.

Overall Application Structure

If you’ve read my articles about Model-View-Controller-Interactor (MVCI), then you have an idea about how to keep your business logic out of your layout code, and how to keep your layout code out of your business logic. But how do you put it all together to make a big, complicated application that does a lot of back-end stuff?

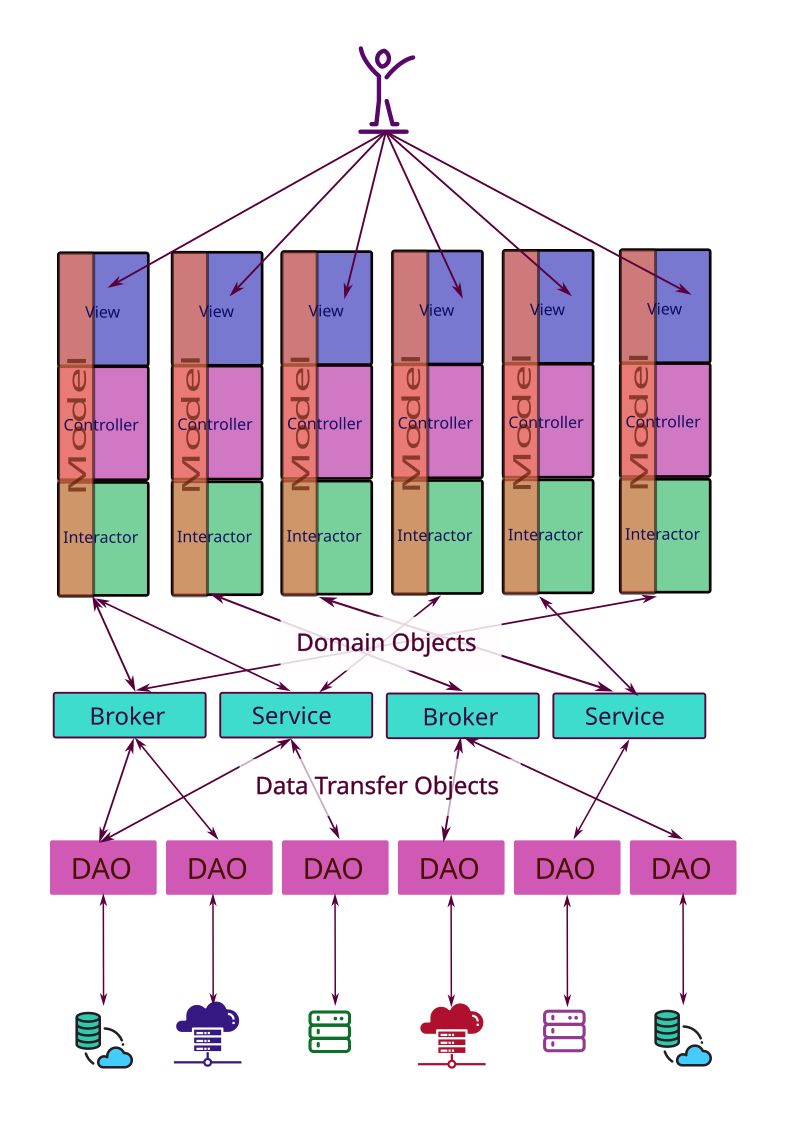

Let’s start by takeing a 10,000’ look at how an application goes together:

At the very top we have the user, who interacts with the View layer of our MVCI frameworks. At the bottom, we have a collection of databases, legacy systems, external systems, business partner systems and external resources.

Let’s look at all of the parts, and what they do:

The Model-View-Controller-Interactor (MVCI) Frameworks

I’ve drawn this out using MVCI, but the rest of the structure works almost as well when you are using MVC, MVP or MVVM. In those frameworks, substitute the Model for the MVCI Interactor when thinking about how they connect down to the Broker/Service layer.

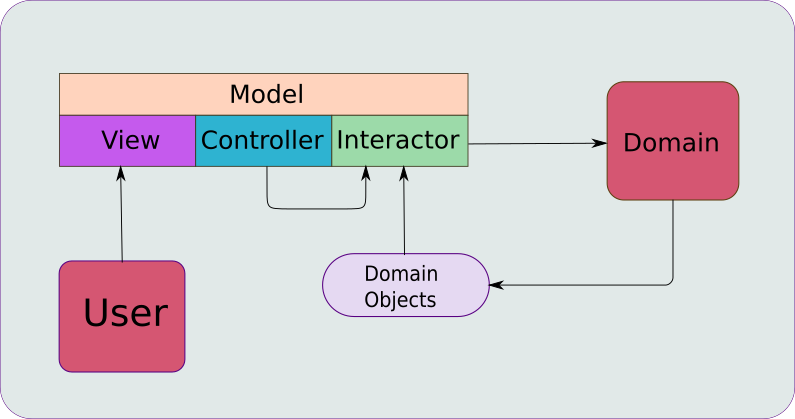

In the diagram, the MVCI parts look like this:

If you’ve read some of the other articles, you may have come upon this diagram, instead:

They are essentialy the same, but the second one shows the external interactions.

In a practical sense each one of the vertical MVCI constructs provides a specific set of features to the application. For instance, the one on the far left might be the main menu for the application and handle login and authentication, the next one might provide Customer search and lookup, the next one might provide Customer CRUD functions. Other ones might provide Order lookup, and then Order CRUD, inventory inquiry, and so on.

When you look at this way, each feature in the application slices vertically from the View at the top right down to the external applications it might need to access at the bottom. If you were going to implement a new feature to, say, add a field onto a screen, then implementing it would involve the layout changes, adding the corresponding data to the Model, then adding it to a Domain Object and updating the Broker to populate and retrieve it. Finally, you’d need to add it to the DTO so that it can be passed to a DAO, which would then need to be updated to pack and unpack it, and then updates to the related database to store it.

Scope of a feature, then, is related to the width of that vertical slice, given that it always has to extend from the top right down to the bottom.

The MVCI framework itself is divided into 4 parts. Let’s take a very quick look at the parts:

Model

Unlike in MVC, MVVM, or MVP, the Model in MVCI is simply a Presentation Model. This means that it holds data used by the View in a format best suited for the View. In JavaFX, this means that the data elements are JavaFX Observable types, which can be bound to Properties in the layout Nodes. Note that all of the other three components of MVCI (the Controller, the View and the Interactor) share a reference to the Model, so all of the components can access the data.

In practice, the View accesses the elements of the Model as Observable types via Binding. At the other end, the Interactor virtually ignores the Observable nature of these elements and access their values directly. In this way, the Model provides a data pipeline between the business logic and the GUI without either end knowing about the existence of the other.

View

This is the piece that interacts with the User. This is NOT just the layout, it’s also the connection to the Presentation Model and the configuration of the Nodes included how they will act when activated. This means the definition of Events due to mouse clicks, keystrokes and anything else that can happen in the GUI.

In practice, the View will usually be an implementation of the JavaFX Region class, which is created and configured by a ViewBuilder class, which is just an implementation of the JavaFX Builder<Region> interface. So you won’t have a class called View in your MVCI implementation. Rather, you’ll usually have Controller.getView() method which delegates to Builder.build() method.

Controller

The Controller is the central component of MVCI. It handles instantiation of all of the other components and provides the facility for the View to invoke business logic in the Interactor. The Controller is the ONLY component with public methods that can be invoked from outside the MVCI framework. Therefore, it is the component which allows MVCI frameworks to be connected together in a larger application.

While the View and the Interactor share data freely via the Model, the Controller is the conduit for actions initiated in the View that need to invoke methods in the Interactor. Think about something like a “Save” Button. Clicking on it needs to invoke some kind of activity in the Interactor. It doesn’t need to transmit any data, because the Model is already up-to-date with the View (because of the Bindings), and accessible to the Interactor. The Controller provides some sort of functional element, like a Consumer or a Runnable to the View, and the View will invoke it when needed. This functional element will handle any background threading that’s require, and call a method in the Interactor.

Interactor

This is the component that contains the business/application logic of the framework. It’s the only MVCI component which is allowed to deal with Domain Objects, and a large part of its job is to translate data between the Model and the Domain Objects in order to facilitate connections to a persistence layer.

Although any of the frameworks is essentially a GUI oriented construct, the Interactor is the piece where you could, if you thought it had value, design without any knowledge of JavaFX. By this, I mean that you write it so that it would compile without any import javafx.* statements. You could write your Model with the fields designed as JavaFX Beans, and then only access the delegating getter and setter methods for the values. Then the Interactor wouldn’t even be aware that they were Observable types at all.

In practice I prefer to see all of the business logic an one place, and that includes establishing Binding relationships between elements of the Model. That usually means that some code in your Interactor will have to do some JavaFX work to create the Bindings.

Domain Objects

Domain Objects represent fundamental groupings of application data and logic within the context of a “domain”. In a business application these would be called “Business Objects”, but “Domain Objects” is a more generalized term that encompasses any kind of application. Note that a Domain Object is not necessarily a POJO and is not restricted to containing only data elements. More about this later.

As an example, a Customer might be a Domain Object in an application. It could contain data elements including an account number, a name, address information and a list of recent purchases. Whatever makes sense within the context of the business (or, if you like, the domain). It’s also allowed to have whatever logic makes sense in its context. For instance, maybe we have a field for birth date. From birthDate we might have several functions that return age in years with rounding to the nearest year. This might not be of value if we need the age in years to determine eligibility to purchase alchohol, so we might need a function to calculate age rounded down. Maybe we need a function to calculate age in days, and we need to make sure that we take into account leap years. It’s fine to have these functions in Customer, as well as lots of other logic as required.

Brokers and Services

I’m not sure if anyone else uses the term “Broker”, but I see it as a sub-type of “Service” that’s primarily concerned with creating or saving Domain Objects to/from a persistence layer. “Services” also deal in Domain Objects, but have a broader functionality that can include just about all of the business/application logic that spans the entire application. If you’re vigorously appling DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself), then any time that you find yourself writing the same logic in two different Interactors, you should push that logic down into Broker/Service layer and expose it as a public method.

Brokers all understand how to use one or more Data Access Objects (DAO’s) and understand the format of the data that they need to transfer to and from those DAO’s. It’s entirely possible that a Broker will need to connect to two or more DOA’s in order to complete a request. For instance, in our Customer example in the previous section, that recent purchase information may come from a sales application or database, while the rest may come from a CRM system. So the CustomerBroker would need to access methods in both the CrmDao and the SalesDao, which is fine.

Brokers also understand the structure of the Data Transfer Objects (DTO’s) that will be transfered to and from the DOA layer. The use the DTO’s to assemble Domain Objects that are the building blocks of application logic.

So, generally speaking, a Broker will get a request to retrieve some kind of data from external services and it will know which DOA’s to contact and how to call their public methods in order to get the data that it needs. It will then assemble this data into Domain Objects which it will return to the requesting Interactor (or other Broker, or whatever). Conversely, it would receive a Domain Object from an Interactor in a request to save the data, which it would then transate into calls to DOA methods to perform the save.

Data Transfer Objects (DTO`s)

DTO’s are used…wait for it…to transfer data between the the DAO’s and the Brokers/Services. They represent a contract, if you like, between those two end points. The Broker asks for information, and the structure of the DTO defines what data elements will be delivered and how they will be structured.

Unlike Domain Objects, Data Transfer Objects are pure data, essentially POJO’s. In Java, you could use Record classes and in Kotlin you can use Data classes.

Beyond that, it’s probably practical to set up DTO’s so that they are easily serializeable. Then your DAO can simply use standard libraries to convert JSON data from a REST API into a DTO object.

Data Access Objects (DAO’s)

DAO’s are the objects that actually connect to the various databases, applications, websites and file systems that the applications need to run. They can be used to provide persistence, but these external systems can provide virtually any service you can visualize.

In the diagram, I’ve shown each DOA connecting to a single external service because that’s probably the most common real-life situation. However, there’s no real rule about this. If it makes more sense to have a single DOA connect to two services - perhaps because the presence of multiple services is irrelevant to the business logic at the Broker level - then build it that way.

DOA’s know everything they need to about the services that they connect to. If they are connecting to a database, then they are aware of the tables and fields in the database and how to construct queries to retrieve data from the database. They contain logic to deal with connection limitations, authentication, caching and performance optimization. The are also aware of the structure of the data that they will receive or send to/from the service.

Design Decisions

Within this overall structure, there’s lots and lots of room for a team to argue about how to best implement any specific aspect of the application design. Lots of places to make bad decisions - and good ones.

Hiding and Revealing

Pretty much all of this application structure is intended to serve one purpose - limit and control coupling throughout the application.

Too much coupling is deadly to an application. Imagine having to refactor multiple Views because some external business partner upgraded their database! It can happen. Coupling is the single most important factor in how complicated it becomes to make a change or enhancement to your application.

The best way to understand coupling is to think of it in terms of hiding and sharing, responsibility and delegation. Write every class so that it jealously guards it secrets, and desparately clings to every bit of power and responsibility that it has a right to. Shared responsibility may be great for human teams and teamwork, but it’s 100% wrong in an application design.

If you look at the application structure, you’ll see that every single layer is designed to insulate the layers above and below it from the layers on the other side - to the extent that they are not even aware of the existence of any of other elements. And…if they aren’t even aware of them, then they cannot be coupled to them.

You’ll also notice that virtually all of the functional coupling is downwards. That is to say, that all of the elements contain references only to the elements immediately below them, and can therefore only call methods in the elements below them. For instance, no DOA can call Broker/Service method, and no Brokers can call Interactor methods. At the other end, the View calls Controller methods, but exposes no methods to the Controller. As a subclass of Region the View exposes Region methods to whatever layout element contains in in the GUI, but cannot call any methods of that layout element.

The DOA’s are designed to isolate the Broker/Service layer from the external services. There’s simply no coupling between the external services and the Brokers because they aren’t even aware of each other.

The Data Transfer Objects remove coupling between the data structures from the external services and the Brokers. The DTO’s are just Java Data or Record classes, and they have been sanitized from any connection to the original external structure. They represent the contract between the Broker and the DAO, “You ask for information, this is what I’ll send you, and I’ll send it to you in this format, even if the external source is completely changed”.

Putting Code in the Right Place

Another key component to limiting coupling is to put your code in the right place. Code that’s in the wrong place automatically increases coupling because it inevitably means you have to reach into some other place to get information that you need.

There are two techniques that you can use to help ensure that you put your code in the right place…

Don’t Repeat Yourself

DRY is probably the most important rule, but it also so easy to break. Personally, I don’t think you can “over-apply” DRY, even though I have seen arguments to the contrary. Repeated code can also hide on you, especially if it’s written at different times by different programmers.

Using DRY results in putting code in the right place because it tends to ensure that your logic is unique to the place in your system where the data is located. As an example, let’s say that you found the same logic in two different Interactors. Clearly, that logic is not unique to the data present in either Interactor. There’s a very good chance that you can move that logic into a Broker/Service class and expose it as a public method. There’s also a very good chance that the logic centres around the data that is “native” to that Broker or Service.

Avoid “Feature Envy”

“Feature Envy” is when one class contains logic that really should be a feature, or a public method, in another class.

A good indicator of this is when you have a block of code in a class that primarily uses several fields or methods of just a different single class. In that case, the logic probably should be incorporated into that other class. Any local data used in the original block of code can be passed as a parameter.

There’s a number of benefits to removing feature envy…

First, as a public method testing is much, much easier than as a block of code incorporated inside another method, which might even be private.

Secondly, left in the first class it clutters up the logic which is actually unique to that class. This makes it much harder to understand and maintain that code.

Thirdly, it’s almost a prerequite to violating DRY.

Finally, and most importantly, it increases coupling. Now you have a block of code which is dependent on the implementation of several fields and methods of some other class. If any of those change, then it could break your logic. And the programmer who wants to change any of those implementations has to be aware of how they are used throughout the application. If the logic is incorporated into that other class and exposed as a public method, then any programmer than changes the internals of that class is also responsible for ensuring that they don’t break that public method.

Static Methods

One thing that eventually will happen, is that you look at Customer and you’re shocked to see how much code it’s grown to hold. You’ll feel that your class has become bloated and unwieldy. And you might be right.

Then you’ll look at CustomerBroker and you’ll say to yourself, “This is a good place to put methods that manipulate Customer”. And you’ll start moving stuff out of Customer and start delgating to static methods in CustomerBroker, passing them Customer.this. Things like Customer.canBuyAlchohol() will delegate to CustomerBroker.canBuyAlchohol(Customer customer).

And this will reduce the bloat in your domain objects.

Or will it?

Honestly, when you create a static method in a class which is only called by other class, especially just one method in that other class, all you’ve really done is spread your class across two classes. There’s no practical advantage to it. Even if you cheat.

Cheat?

So you make your delagate methods not static. But it’s still effectively static because it doesn’t use or update the state of the Broker class. So it could easily be static if you wanted - but now you have to pass an instance of the Broker to the Domain Object when it’s created. Or you bypass the delegating function in the Domain Object to pass the Domain Object directly to the delegate method in the Broker from the Interactor. Now you’ve made it worse because you’ve increased the coupling between the Interactor and the Broker.

Conclusion

The truth is that any large application that does real work is going to have ample complications to keep you busy for a long time. It will seem like none of the design decisions are simple, and everything has some twist that makes life more difficult.

Having a solid idea about how your application architecture will help to reduce the coupling through the application can make a lot of these decisions much easier.

The nice thing about MVCI with this architecture is that it just works. MVCI provides exactly the things you need to write a Reactive JavaFX GUI connected to business logic. The tiered structure below it isolates everything else so that it doesn’t become a tangled mess of logical spaghetti.