Introduction

I was looking at a question on StackOverflow.com about JavaFX where the OP was doing some complicated things including manual styling in his code. He had four states that he wanted to style: “active”, “inactive”, “highlighted” and “error”. I was thinking, as I looked at the code, that it must be easier to do this using stylesheets and PseudoClasses.

But PseudoClasses classes only work in an “on/off” fashion. And the OP for this question had a set of Boolean flags with big blocks of code that looked at the values of the flags, turning them on and off and applying different stylings according to the value. All of which, of course, was in his layout code.

It occurred to me that any time you’ve got a set of values where only one can be true, you could probably handle it better with a Enum of some sort. And I wondered how you would integrate that with the JavaFX PseudoClass system to handle dynamic styling based on a set of mutually exclusive values.

That’s what we’re going to look at here.

PseudoClasses

What is a “PseudoClass”?

A PseudoClass is a way to provide temporary styling on a Node (usually) connected to a BooleanProperty in the layout code. For instance, a Button can have a “disabled” status which is controlled through Button.disabledProperty(). When you look through the CSS stylesheet, you’ll find something equivalent to .button: disabled {}. Whatever is set inside the {} is applied to the Button only when the disabled PseudoClass is applied to it.

There are a number of pre-defined PseudoClasses in JavaFX that are attached to various Properties in Node and its subclasses. Besides disabled, there’s armed, selected, focused and default, just to name a few. You can even combine them together into something like .button :armed :focused. Not all of theses PseudoClasses are available for every Node subclass.

Without customizing the code for any of these standard PseudoClasses, you can implement your own styling for them just by creating a stylesheet with an entry for selector: pseudoclass (using real values for selector and pseudoclass).

Custom PseudoClasses

You can also create your own PseudoClasses, and the mechanism to connect JavaFX Nodes to your custom PseudoClass is simple, although badly explained in the JavaDocs.

The process is easy to describe: Create an instance of PseudoClass with an associated CSS identifier (like “selected”), then call Node.pseudoClassStateChanged() for whatever Node you want, specifying your PseudoClass instance and with a true or false.

That’s all there is to it, and this code will do it:

val myPseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("flashing")

myLabel.pseudoClassStateChanged(myPseudoClass, true)

Generally speaking, though, you wouldn’t do it this way. First, myPseudoClass should probably by static, or at least a singleton - in Kotlin we’d put it inside a companion object. In Java you’d make it static final.

Secondly, you’ll normally associate the control of your PseudoClass with a BooleanProperty and then put a Subscription or a Listener on it to call Node.pseudoClassStateChanged(). This would look like this:

companion object {

val myPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("flashing")

}

.

.

.

model.someBooleanProperty.subscribe{ newVal ->

myLabel.pseudoClassStateChanged(myPseudoClass, newVal)

}

From the JavaDocs

The JavaDocs are a bit bewildering because of the sample code included in the introduction. We should probably look at this code just to understand how it works:

public boolean isMagic() {

return magic.get();

}

public BooleanProperty magicProperty() {

return magic;

}

public BooleanProperty magic = new BooleanPropertyBase(false) {

@Override protected void invalidated() {

pseudoClassStateChanged(MAGIC_PSEUDO_CLASS, get());

}

@Override public Object getBean() {

return MyControl.this;

}

@Override public String getName() {

return "magic";

}

}

private static final PseudoClass

MAGIC_PSEUDO_CLASS = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("xyzzy");

The first thing, that’s not explained at all, is that this code needs to exist inside the MyControl class. This means that this implementation is intended to be used inside a custom class that is a subclass of Node (because it calls pseudoClassStateChanged()).

The other slightly confusing (and the most important) thing is that they’ve overriden BooleanProperty.invalidated(). Essentially, this is the same as adding an InvalidationListener to the Property. It’s not a bad approach, and it’s something that I’ve been calling an Action Property since it’s now a Property that also does something else - in this case trigger a PseudoClass state change.

The problem with this approach is that it requires extending some Node subclass to create a custom class, and then you’re burdened with that custom class that you have to keep track of.

It’s not necessary and, as we saw above, it can be done with two lines of code using an external BooleanProperty.

Multiple Exclusive States

What if you want to establish a styling state for a Node that doesn’t just have two values? By this I mean, instead of just on and off, you have state1, state2, state3 and so on.

PseudoClasses on work with on and off. But you can establish a number of PseudoClasses, each of which can either be on or off and then combine them together somehow such that if one of them turns on, then the others all turn off.

The obvious structure for a data element that can have one, and only one, of a discrete number of values is Enum. How can we turn an Enum into a mechanism to control a set of PseudoClasses that work together as described above?

We’re going to look at this in both Kotlin and Java, since they are significantly different.

Kotlin

In Kotlin, an Enum can implement an Interface. We’ll start there:

interface PseudoClassSupplier {

fun getPseudoClass(): PseudoClass

}

Just one function: getPseudoClass().

Here’s why we want to do this:

fun Node.bindPseudoClassEnum(property: ObservableObjectValue<out PseudoClassSupplier>) {

property.subscribe { oldValue, newValue ->

oldValue?.let { pseudoClassStateChanged(it.getPseudoClass(), false) }

newValue?.let { pseudoClassStateChanged(it.getPseudoClass(), true) }

}

property.value?.getPseudoClass()?.let { pseudoClassStateChanged(it, true) }

}

This is an extension function on Node, which means it will work for just about anything that you might possibly want to style via a PseudoClass. We pass it an ObservableObjectValue that contains something that can supply PseudoClassSupplier. This method adds a Subscription that supplies both the old and the new values of the ObservableObjectValue. When the Subscription is triggered, we set the state of the old PseudoClass to off for this Node, and set it to on for the new value. This is done with null safety checking since we have no control over whether or not the ObservableObjectValue is empty (or was empty).

Finally, we use the initial value in the ObservableObjectValue to turn the state to on for this Node, if it’s populated.

How do we use this then?

Here’s an example of an Enum that implements PseudoClassSupplier and can be used in our ObservableObjectValue<out PseudoClassSupplier>:

enum class StatusPseudoClass : PseudoClassSupplier {

NORMAL, WARNING, ERROR, FAILED;

companion object PseudoClasses {

val normalPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("normal")

val warningPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("warning")

val errorPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("error")

val failedPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("failed")

}

override fun getPseudoClass() = when (this) {

NORMAL -> normalPseudoClass

WARNING -> warningPseudoClass

ERROR -> errorPseudoClass

FAILED -> failedPseudoClass

}

}

The tricky thing here is that we want the instantiations of the PseudoClasses to be effectively static, so we need to use a companion object to contain them. However, we cannot reference the companion object in the constructors of the Enum elements (I tried), so we need to handle it in the body of getPseudoClass(). Hence the when (this) {} structure.

The result is that the specifics about any particular implementation of this approach are contained neatly into a single Enum class. Once it has been established, it’s easy to replicate over and over again for any Enum you can think of.

Let’s look at how to implement this:

class EnumPseudoClassApp : Application() {

override fun start(stage: Stage) {

stage.scene = Scene(createContent(), 380.0, 200.0).apply {

EnumPseudoClassApp::class.java.getResource("test.css")?.toString()?.let { stylesheets += it }

}

stage.title = "PseudoClasses Wow!"

stage.show()

}

private fun createContent(): Region = VBox(10.0).apply {

val status: ObjectProperty<StatusPseudoClass> = SimpleObjectProperty()

children += Label("This is a Label").apply {

styleClass += "status-label"

bindPseudoClassEnum(status)

}

val toggleGroup = ToggleGroup()

children += HBox(10.0).apply {

children += ToggleButton("Normal").apply {

setOnAction { status.value = StatusPseudoClass.NORMAL }

toggleGroup.toggles += this

}

children += ToggleButton("Warning").apply {

setOnAction { status.value = StatusPseudoClass.WARNING }

toggleGroup.toggles += this

}

children += ToggleButton("Error").apply {

setOnAction { status.value = StatusPseudoClass.ERROR }

toggleGroup.toggles += this

}

children += ToggleButton("Failed").apply {

setOnAction { status.value = StatusPseudoClass.FAILED }

toggleGroup.toggles += this

}

}

padding = Insets(50.0)

}

}

fun main() = Application.launch(EnumPseudoClassApp::class.java)

Here’s the style sheet:

.root {}

.status-label {

-fx-font-size: 14px;

-fx-font-weight: bold;

-fx-text-fill: blue;

}

.status-label: normal {

-fx-text-fill: black;

}

.status-label: warning {

-fx-text-fill: orange;

}

.status-label: error {

-fx-text-fill: red;

}

.status-label: failed {

-fx-text-fill: green;

}

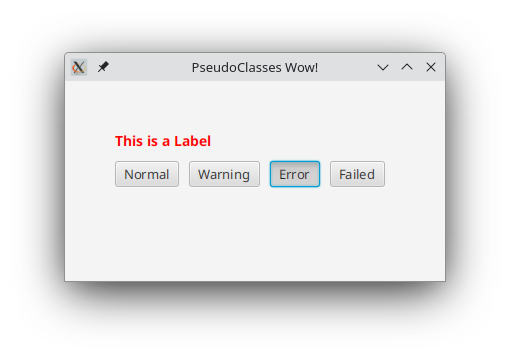

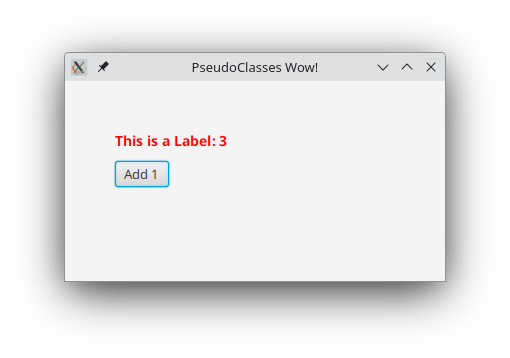

And it looks like this:

I put the actions into ToggleButtons in a ToggleGroup just make it clear when one has been selected. The external Property would probably be in a Model somewhere, but here we just have the local variable, status. The PseudoClasses are applied to a Label via Label.bindPseudoClassEnum(status). The actual changes to the Property are handled by the ToggleButton actions.

Perhaps the most important thing here is that the PseudoClass handling code isn’t in the layout code. It’s basically “plumbing” and isn’t particularly specific to this layout. I could see a case for putting this Enum class itself away in a utility package somewhere so that it can be used over and over. When you think about it, having the statuses “NORMAL”, “WARNING”, “ERROR” and “FAIL” (or some variation of this) is a pretty universal concept, and could be used over and over without modification.

But it still looks like a lot of code in the layout, mostly because of all of the Buttons. Let’s change it a little.

private fun createContent(): Region = VBox(10.0).apply {

val amount: ObjectProperty<Int> = SimpleObjectProperty(-1)

children += Label().apply {

styleClass += "status-label"

textProperty().bind(amount.map { "This is a Label: $it" })

bindPseudoClassEnum(amount.map {

when {

it < 0 -> StatusPseudoClass.FAILED

it == 0 -> StatusPseudoClass.NORMAL

it < 3 -> StatusPseudoClass.WARNING

else -> StatusPseudoClass.ERROR

}

})

}

children += Button("Add 1").apply {

setOnAction { amount.value += 1 }

}

padding = Insets(50.0)

}

Everything else remains the same.

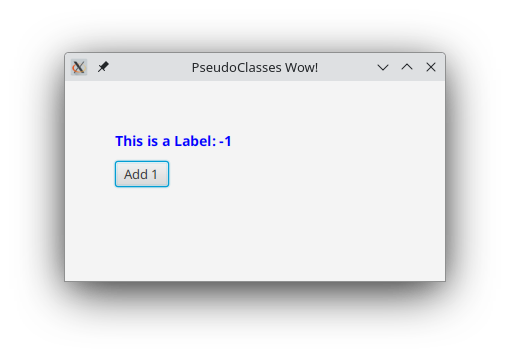

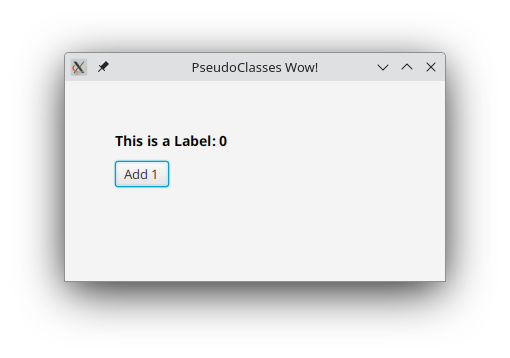

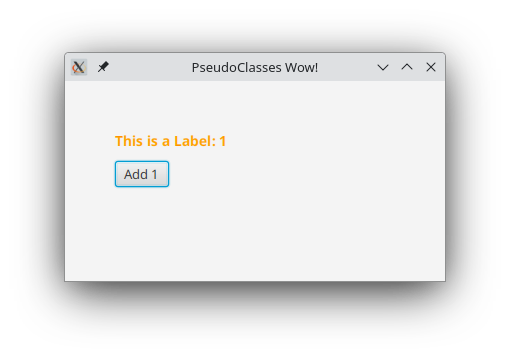

The multiple Buttons are gone, and now we just have a single Button that increments an Integer Property. The PseudoClass is now connected to this Integer Property through a Binding that uses ObservableValue.map{} to convert it to a value of the StatusPseudoClass Enum. The map{} uses a variant of when which is the Kotlin equivalent to Java’s switch().

The value starts at -1 and as the Button is clicked it cyles from FAILED through all of the other values, and the colour of the Label changes.

Even if you are going to be programming in Kotlin, the Java example is worth looking at because it uses a different approach that will also work in Kotlin.

Java

Java also allows you to have an Enum implement an Interface, so we’ll start off from there for Java, too. First, the Interface:

public interface PseudoClassProvider {

PseudoClass getPseudoClass();

}

I changed the name here, just so it wouldn’t collide with the Kotlin Interface name in my project.

And then we’ll create an Enum that implements this Interface:

public enum StatusEnum implements PseudoClassProvider {

NORMAL {

@Override

public PseudoClass getPseudoClass() {

return normal;

}

}, WARNING {

@Override

public PseudoClass getPseudoClass() {

return warning;

}

}, ERROR {

@Override

public PseudoClass getPseudoClass() {

return error;

}

}, FAILED {

@Override

public PseudoClass getPseudoClass() {

return failed;

}

};

private static final PseudoClass normal = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("normal");

private static final PseudoClass warning = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("warning");

private static final PseudoClass error = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("error");

private static final PseudoClass failed = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("failed");

}

This is a little bit different from the Kotlin version, which could have also been done this way. Here, instead of having a switch() statement to determine the PseudoClass, we’re overriding the Interface for each value of the Enum. Essentially, we’re going with inheritance here instead of branching, which is maybe a little bit more of a Java approach.

Now, in Java we don’t have extension functions. You could create a static method in a library class, and pass it both the Node and the Property and have it create the Subscription, and that would be fine. In fact, if you were already building a library of static methods to provide builders and helper methods (and you should be), then it’s probably more than fine because it would fit in with that approach.

But for this example, I wanted something a little more self-contained. So what we have here is an “Action Property”:

public class EnumPseudoClassProperty<T extends PseudoClassProvider> extends ObjectPropertyBase<T> {

private final Node node;

private PseudoClassProvider oldValue;

public EnumPseudoClassProperty(Node node) {

this.node = node;

}

public EnumPseudoClassProperty(Node node, T initialValue) {

this.node = node;

this.set(initialValue);

}

@Override

protected void invalidated() {

if (oldValue != null) {

node.pseudoClassStateChanged(oldValue.getPseudoClass(), false);

}

if (getValue() != null) {

node.pseudoClassStateChanged(getValue().getPseudoClass(), true);

}

oldValue = getValue();

}

@Override

public Object getBean() {

return node;

}

@Override

public String getName() {

return "";

}

}

This is a generic class that wraps some class, T, that extends PseudoClassProvider, meaning that it implements getPseudoClass(). So T can be any class that implements PseudoClassProvider.

Next, we get to the “Action Property” part. You can read more about this in this article if you like. We are overriding the method, invalidated(), which JavaFX provides for us so that we can automatically make our Property take some action whenever its value changes. It’s equivalent to addListener() or subscribe(), except that it’s contained within the Property itself.

The only other quirk here is that we have to keep track of the old value ourselves in those cases where we care about the old value. And here, we do. It’s not a big deal, though, we just introduce a field and update it at the end of our invalidated() code.

Of course, to make this work, we need to provide the Node associated with the PseudoClasses, so it’s passed in the constructor. Also, since this extends from ObjectPropertyBase, we need to provide implementations for getName() and getBean(). Once again, if you want to know more about Action Properties (my name for them), then you should read the other article.

All that’s left is to implement it. Here’s the Application:

public class EnumPseudoApplication extends Application {

@Override

public void start(Stage stage) throws Exception {

Scene scene = new Scene(createContent(), 300, 240);

scene.getStylesheets().add(EnumPseudoApplication.class.getResource("test.css").toExternalForm());

stage.setScene(scene);

stage.show();

}

private Region createContent() {

VBox results = new VBox(20);

Label label = new Label("This is the label");

label.getStyleClass().add("status-label");

EnumPseudoClassProperty<StatusEnum> status = new EnumPseudoClassProperty<>(label, StatusEnum.FAILED);

results.getChildren().addAll(label, createButton("Failed", status, StatusEnum.FAILED),

createButton("Normal", status, StatusEnum.NORMAL),

createButton("Warning", status, StatusEnum.WARNING),

createButton("Error", status, StatusEnum.ERROR));

return results;

}

private Region createButton(String text, EnumPseudoClassProperty<StatusEnum> property, StatusEnum newValue) {

Button button = new Button(text);

button.setOnAction(evt -> property.set(newValue));

return button;

}

}

Here we instantiate the Property as a variable so that we can pass it around to the Button builder method so that it can be updated in the onAction EventHandler.

The style sheet is the same one from the Kotlin example.

You Don’t Have to Use Enum

Enum is a natural fit for this kind of a use because it works much like ToggleButtons in a ToggleGroup. Only one can be selected at a time, and selecting any one value automatically turns any other ones off. Enum gives the framework, and all we need to do is provide the mechanics for turning the selected and de-selected values on and off.

But there’s no rule that we have to use an Enum. Any class that implements the PseudoClassProvider Interface, or that can be extended to implement that Interface will work. In Kotlin, you could probably use a Sealed Class very effectively for this.

But you don’t have to stick to this kind of approach. You could have a custom class that implements PseudoClassProvider but stores an immutable reference to a PseudoClass instance in a field. Then put different instances of this class into a Property.

Classes That Can’t Implement PseudoClassSupplier

It would be really cool to be able to extend Int in Kotlin (or Integer in Java) to implement PseudoClassSupplier. Then you could define Int.getPseudoClass() to return a PseudoClass based on a value or range of values for Int.

But you can’t. So what do you do?

You can use an Action Property to contain everything:

class IntRangePseudoProperty(private val node:Node) : ObjectPropertyBase<Int>() {

private var oldValue : Int? = null

init {

invalidated()

}

override fun invalidated() {

oldValue?.let{node.pseudoClassStateChanged(getPseudoClassFromValue(it), false)}

value?.let{node.pseudoClassStateChanged(getPseudoClassFromValue(it), true)}

oldValue = value

}

private fun getPseudoClassFromValue(theValue: Int): PseudoClass = when {

theValue < 0 -> failedPseudoClass

theValue == 0 -> normalPseudoClass

theValue < 3 -> warningPseudoClass

else -> errorPseudoClass

}

companion object PseudoClasses {

val normalPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("normal")

val warningPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("warning")

val errorPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("error")

val failedPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("failed")

}

override fun getBean(): Any = node

override fun getName(): String = "Integer Range"

}

Once again, we extend from ObjectPropertyBase and provide getBean() and getName() implementations that do reasonable things, even though it’s highly unlikely these will ever be called.

We override invalidated() and put the PseudoClass state change logic in there. To avoid repetition, the actual range calculation has been pulled out into its own function.

But what if you wanted to abstract it a little bit? Splitting out that getPseudoClassFromValue() logic into its own method suggests that a functional element could be used. What if we did this:

class PseudoProperty<T>(private val node: Node, private val translator: (T) -> PseudoClass) : ObjectPropertyBase<T>() {

private var oldValue: T? = null

init {

invalidated()

}

override fun invalidated() {

oldValue?.let { node.pseudoClassStateChanged(translator(it), false) }

value?.let { node.pseudoClassStateChanged(translator(it), true) }

oldValue = value

}

override fun getBean(): Any = node

override fun getName(): String = "PseudoClass Property"

}

Now we have a generic Action Property<T> that will use a Function (that’s what (T) -> PseudoClass is) that will take an T and return a PseudoClass. That Function is given in its constructor.

However, since we have static PseudoClasses, we can’t provide an Anonymous InnerClass via a lambda expression, because we cannot declare static (or companion objects) inside those. So we’ll have to create a class for it:

class IntRangeTranslator : (Int) -> PseudoClass {

override fun invoke(theValue: Int): PseudoClass = when {

theValue < 0 -> failedPseudoClass

theValue == 0 -> normalPseudoClass

theValue < 3 -> warningPseudoClass

else -> errorPseudoClass

}

companion object PseudoClasses {

val normalPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("normal")

val warningPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("warning")

val errorPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("error")

val failedPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("failed")

}

}

That’s nifty. Now we have a Property<T> that we can stick into a libary somewhere so we don’t have to worry about it any more, then we can put the code that’s specific to our use case (the translator), adjacent to our layout code.

class EnumPseudoClassApp : Application() {

override fun start(stage: Stage) {

stage.scene = Scene(createContent(), 380.0, 200.0).apply {

EnumPseudoClassApp::class.java.getResource("test.css")?.toString()?.let { stylesheets += it }

}

stage.title = "PseudoClasses Wow!"

stage.show()

}

private fun createContent(): Region = VBox(10.0).apply {

val amount: ObjectProperty<Int> = SimpleObjectProperty(-1)

children += Label().apply {

styleClass += "status-label"

textProperty().bind(amount.map { "This is a Label: $it" })

PseudoProperty(this, IntRangeTranslator()).bind(amount)

}

children += Button("Add 1").apply {

setOnAction { amount.value += 1 }

}

padding = Insets(50.0)

}

}

I have two issues with this approach:

-

We have this “hanging” instantiation of

PseudoPropertywithout any references to it or uses of it anywhere. So it feels more like it should be a method invocation rather than an instantiation. -

We need to hang on to

amountand then bind it to our anonymousPseudoPropertyinside theLabel().apply{}block. This is because we need a reference to theLabelin order to instantiate thePseudoPropertyso we cannot instantiate it outside theapply{}block unless we make a variable refernce to theLabelso that we can pass it to the constructor ofPseudoProperty. And all of that feels wrong to me.

What if we remove the requirement to pass the Node in the constructor of PseudoProperty?

class SimplePseudoProperty<T>(initialValue: T) : ObjectPropertyBase<T>() {

private var translator: ((T) -> PseudoClass)? = null

private var oldValue: T? = null

private var node: Node? = null

infix fun setNode(newNode: Node)= apply {

node = newNode

}

infix fun setTranslator(newTranslator: ((T) -> PseudoClass)?) = apply {

translator = newTranslator

}

init {

value = initialValue

invalidated()

}

override fun invalidated() {

println("Invalidated $value")

translator?.let { translator ->

oldValue?.let { node?.pseudoClassStateChanged(translator(it), false) }

value?.let { node?.pseudoClassStateChanged(translator(it), true) }

}

oldValue = value

}

override fun getBean(): Any = node ?: Unit

override fun getName(): String = "PseudoClass Property"

}

Additionally, we’ve also gotten rid of the reequirement to supply the translator in the constructor. Now both the Node and the translator can be supplied via decorators. If you were writing this as a library utility class, you’d probably want to make node and translator effectively immutable, or supply logic to handle changes to these fields in a way that makes sense to you.

Now, we can transform amount into our PseudoProperty instead:

class EnumPseudoClassApp : Application() {

override fun start(stage: Stage) {

stage.scene = Scene(createContent(), 380.0, 200.0).apply {

EnumPseudoClassApp::class.java.getResource("test.css")?.toString()?.let { stylesheets += it }

}

stage.title = "PseudoClasses Wow!"

stage.show()

}

private fun createContent(): Region = VBox(10.0).apply {

val amount = PseudoProperty(-1)

amount.setTranslator(IntRangeTranslator())

children += Label().apply {

styleClass += "status-label"

textProperty().bind(amount.map { "This is a Label: $it" })

amount.setNode(this)

}

children += Button("Add 1").apply {

setOnAction { amount.value += 1 }

}

padding = Insets(50.0)

}

}

Finally, if we want to get rid of IntRangeTranslator and use a lambda instead, we’ll need to find a home for the static PseudoClasses. But if we’re using a lambda, then we are pretty much into creating something specific for this layout, so there’s no problem putting the PseudoClasses close to the layout, like this:

class EnumPseudoClassApp : Application() {

private val amount = SimplePseudoProperty(-1) setTranslator { theValue ->

when {

theValue < 0 -> failedPseudoClass

theValue == 0 -> normalPseudoClass

theValue < 3 -> warningPseudoClass

else -> errorPseudoClass

}

}

companion object PseudoClasses {

val normalPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("normal")

val warningPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("warning")

val errorPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("error")

val failedPseudoClass: PseudoClass = PseudoClass.getPseudoClass("failed")

}

override fun start(stage: Stage) {

stage.scene = Scene(createContent(), 380.0, 200.0).apply {

EnumPseudoClassApp::class.java.getResource("test.css")?.toString()?.let { stylesheets += it }

}

stage.title = "PseudoClasses Wow!"

stage.show()

}

private fun createContent(): Region = VBox(10.0).apply {

children += Label().apply {

styleClass += "status-label"

textProperty().bind(amount.map { "This is a Label: $it" })

amount.setNode(this)

}

children += Button("Add 1").apply {

setOnAction { amount.value += 1 }

}

padding = Insets(50.0)

}

}

What I like about this approach is that the things which are specific to this layout; the tranlation and the actual PseudoClasses are close to, but not in the layout code. But the things that are generic, the plumbing, is somewhere else.

But…

Using This in a Framework

Here’s the question…Is the translation from number to a classification really part of the View?

Not the translation to PseudoClasses, that’s definitely the role of the View, but the definition of the ranges - <0, 0,1-2 and 3+ - are those ranges purely for the View? Or are they an expression of some business/application rule?

Because, if the answer is that the range determination is business/application logic, then that code belongs in the Interactor (or the Model, if you’re using MVC or MVVM).

Let’s look at the example of a custom Enum with the PseudoClasses baked in. Does the inclusion of the PseudoClasses make it a View-only element? Is it acceptable to have a Model field with a type of ObjectProperty<StatusPseudoClass> that the Interactor can see and access?

Personally, I think that, although there’s no way that the Interactor should ever be calling getPseudoClass(), any attempt to remove that method from the Enum and then replace its functionality with something visible only to the View just gets needlessly complicated. An understanding that the Interactor should simple treat StatusPseudoClass and a vanilla Enum should be sufficient. This is in much the same way that the Interactor should treat the ObservableValues in the Model simply as vanilla wrappers for data that it accesses via get() and set(), while ignoring their observability and doing things like adding Listeners to them.

What about SimplePseudoProperty<T>? On the one hand, you can instantiate it as a field in the Model without breaking the framework, although you’ll have to expose it as SimplePseudoProperty<T>. The View can then provide the link to the Node, and possibly the translator if it’s truly just View only.

On the other hand, if the translator rules count as application/business logic, then you’ll have to put it in the Interactor. Technically, this is possible, because the Interactor can invoke SimplePseudoProperty.setTranslator(). However…

You’re then in a framework pickle because there’s no way to define the translator without providing PseudoClasses as an output. And this means that your Interactor is going to have to directly deal with PseudoClasses, which is probably one step too far over the line in terms of coupling.

Specifically, it’s OK for your Interactor to say, “This value of this property is catagorized as such and such”, but it’s totally different for it to say, “This value of this property needs to be styled this way”.

That means that it’s best to create an Enum class that encapsulates the PseudoClasses and then create a Property in the Model to hold it. Then the Interactor can establish the relationship between the data Property and the Enum Property through a Binding using ObservableValue.map() and the View can use the Enum Property to style the Nodes. It would look something like this:

An Example in the MVCI Framework

Let’s look at the previous example transformed to use the MVCI framework. First, the basic components: Model, View, Controller and Interactor…

class Model {

val enumProperty = SimpleObjectProperty<StatusPseudoClass>()

val amountProperty = SimpleObjectProperty<Int>(-1)

}

class Interactor(private val model: Model) {

init {

model.enumProperty.bind(model.amountProperty.map { theValue ->

when {

theValue < 0 -> StatusPseudoClass.FAILED

theValue == 0 -> StatusPseudoClass.NORMAL

theValue < 3 -> StatusPseudoClass.WARNING

else -> StatusPseudoClass.ERROR

}

})

}

}

class Controller {

private val model = Model()

private val interactor = Interactor(model)

private val viewBuilder = ViewBuilder(model)

fun getView() = viewBuilder.build()

}

class ViewBuilder(private val model: Model) : Builder<Region> {

private val statusProperty = PseudoClassSupplierProperty().apply {

bind(model.enumProperty)

}

override fun build(): Region = VBox(10.0).apply {

children += Label().apply {

styleClass += "status-label"

textProperty().bind(model.amountProperty.map { "This is a Label: $it" })

statusProperty.setNode(this)

}

children += Button("Add 1").apply {

setOnAction { model.amountProperty.value += 1 }

}

padding = Insets(50.0)

}

}

We have a Model with just two fields, one is a Property<Int> and the other is a Property<StatusPseudoClass>. StatusPseudoClass is the same as documented earlier. The Interactor has just one function, and that’s to bind the Enum Property of the model to the Int Property via a map{}. The logic inside the map{} is the business logic.

The Controller is boilerplate, and the View is virtually the same output as createContent() gave us in prior examples.

It would have been simpler to just use Node.bindPseudoClassEnum(), but this approach shows how you’d need to do it in Java. We have a “View-only” Action Property which handles the PseudoClass changes for us:

class PseudoClassSupplierProperty : ObjectPropertyBase<PseudoClassSupplier?>() {

private var node: Node? = null

private var oldValue: PseudoClassSupplier? = null

fun setNode(theNode: Node) {

node = theNode

}

init {

invalidated()

}

override fun invalidated() {

node?.let { theNode ->

oldValue?.let { theNode.pseudoClassStateChanged(it.getPseudoClass(), false) }

value?.let { theNode.pseudoClassStateChanged(it.getPseudoClass(), true) }

}

oldValue = value

}

override fun getBean() = node

override fun getName() = ""

}

This is equivalent to the one we used in the Java example, just in Kotlin.

The important thing here is that, to the Interactor, Model.enumProperty is just a wrapper for an Enum. The View, however, doesn’t even use the Enum nature of the Property at all, it just sees it as PseudoClassSupplier. In this way, the Model is a pipeline for business logic to interact with the View without the View or the Interactor knowing about each other.

Conclusion

This ended up being a long discussion about what is basically a simple concept. Almost more important than the actual idea of non-binary PseudoClasses are the considerations around how to implement any new idea in a JavaFX environment.

There are three key points to keep in mind:

-

Isolate the “plumbing” from the implementation.

This allows you to adhere to one of the key concepts of good programming “Don’t Repeat Yourself” (DRY). This also means that you can build the infrastructure once, test it and then use it over and over again. -

As much as possible, keep your layout exclusively layout.

Only include configuration code if it’s truly trivial. By encapsulating the implementation of a particular set ofPseudoClassesinto anEnum, anAction Propertyor a translator away from your layout, it’s easy to maintain and declutters your layout code. -

Don’t mingle your layout and your business logic.

Using a framework is a start, but you have to understand its purpose, and avoid “breaking” it by exposing elements of the View and Model/Interactor to each other. Provide constructs that allow them to communicate with each other without knowing about each other.

Above all, your implementation of something like this has to maintain a pragmatic focus. Loose coupling (which is what this is all about) is supposed to simplify building and maintaining a system. Implementing a super complex solution to achieve loose coupling is often counter-productive.