Introduction

My first year university programming course, way back in the 1980’s, was in Pascal. We were forbidden to use GOTO statements in our assignments:

If any program submitted for an assignment contains a GOTO statement, the code will be deemed to be “non-functional” and the highest grade that it can receive will be a “D”.

In case you’re too young: Pascal was one of the earlier Structured Programming languages. In structured languages, programs are composed of “blocks” of code, and execution would start at the top of each block and exit only at the bottom. Blocks of code could be broken down into smaller blocks using control structures, but each sub-block would be subject to the same rules about starting at the top and ending at the bottom. In this course, you were forbidden to exit a block in the middle by using a GOTO statement.

This has stuck with me for nearly 40 years, but not because of the structured programming concepts. But rather, it’s the idea that a program can run and give the correct answer, and still be incorrect.

I’m not saying that I picked up on this idea when I was 20 years old, but after a decade or so of programming professionally, I definitely had developed an intuition about it.

This is probably the biggest difference between a beginning software developer and a good senior developer. It’s not that the senior developer has more experience with different languages and libraries and domain knowledge - which they certainly do. But that the senior developer - if they are good - has developed an instinct for the kind of patterns that should be avoided, and those that are more likely to be “correct” in any given situation.

Of course, it’s not a binary choice between “right” and “wrong”, but more about the idea that some approaches are objectively better (or worse) than others.

An Example

Let’s look at the kind of mistakes that a beginner can make, and see how more experienced developers pick up on the problems while the beginner misses the most important points that they make…

This example comes from StackOverflow. I’ve converted it to Kotlin, and stripped out the useless FXML stuff since it’s just a GridPane.

class GridPaneAbuse : Application() {

private val gridPane = GridPane()

override fun start(stage: Stage) {

val scene = Scene(createContent(), 400.0, 300.0).apply {

addWidgetStyles()

}

stage.scene = scene

stage.show()

}

private fun createContent(): Region = gridPane.apply {

isGridLinesVisible = true

for (i in 0..2) {

for (j in 0..2) {

val cell = VBox().apply {

minWidth = 60.0

minHeight = 60.0

styleClass += "test-blue"

}

GridPane.setRowIndex(cell, i)

GridPane.setColumnIndex(cell, j)

children.add(cell)

}

}

doStuff()

}

private fun doStuff() {

for (i in 0..2) {

for (j in 0..2) {

val node: Node = gridPane.children[i * 3 + j]

val rowIndex = GridPane.getRowIndex(node)

val colIndex = GridPane.getColumnIndex(node)

if (rowIndex != null && colIndex != null) {

print("($rowIndex,$colIndex) ")

} else {

print("(idk) ")

}

}

println()

}

}

}

fun main() = Application.launch(GridPaneAbuse::class.java)

This just draws a GridPane and populates it with some VBoxes. The method doStuff() attempts to use a pair of nested loops to iterate through all of the children Nodes in the GridPane to lookup their row and column indices from the GridPane. If it gets these indices, then it adds it to the console output. In the event that it cannot get the indices, it prints “idk” instead of the coordinates.

The problem is that this is the output:

(idk) (0,0) (0,1)

(0,2) (1,0) (1,1)

(1,2) (2,0) (2,1)

You can see that the top left corner Node doesn’t have coordinates, and then the remaining locations are displaced, with cell (2,2) missing.

Rather than keep you in suspense, it turns out that the grid-lines cause this behaviour as they are considered “children” of the GridPane. They are placed into a Group and the Group is added to the GridPane's children as element 0.

The best responses came from James_D, who is an absolute monster on StackOverflow. He has a 200K+ reputation, and answers most JavaFX questions before I’ve even seen them. He writes some really comprehensive answers, too, and they are always bang on the money.

Here’s what he said about this problem:

There’s absolutely no guarantee at all that the child nodes of a grid pane are in the order your question assumes (which I think is one child node per cell, filling by row left to right and then moving top to bottom from row to row). Cells can have multiple child nodes, cells can be empty, child nodes can be unassigned to cells, and the order of nodes in the getChildren() list is just the order in which you insert them via something like getChildren().add(…). Without knowing how you added the nodes to the grid, and everything else you did with the grid, the question is unaswerable.

At which point the OP updated his question to add some of the missing information. After that, the grid-lines issue came up and the final comment from the OP on the actual problem was this:

@James_D thank you so much, the problem was in fact that grid lines were turned on(I thought it is just an aesthetic feature) and that somehow for some reason messes indexes of cells. So from: “If I remember correctly, if you make grid lines visible the GridPane internally adds a Path as a child node to display the grid lines.” does that mean the output I recived as “(idk)”was basically related to the path to those added lines?

But let’s be clear here: The grid-lines were NOT the problem!

Very early on the the comment thread, James_D nails the issue:

Generally, though, this doesn’t seem the right way to structure your application. The relationships between the positions should be part of the application state (model); you should not be trying to calculate those things based on the UI classes (view).

and then…

…As I said, though, this simply isn’t the right approach. The relationships between these entities are application state: you should not rely on storing them in the UI objects.

The OP responds with this - which seems like they almost get it, but not quite:

Okay so I should’ve made 2D matrix and connect it with grid pane, and work with matrix right? Well I thought about that but I thought it would waste unnececary (sic) memory so I tried it this way. Now it is kind of late, besides I would like to see why this is being printed and why does this happen with this code.

“Now it is kind of late”. In other words, they are not going to take the time to refactor the application such that it is correctly built.

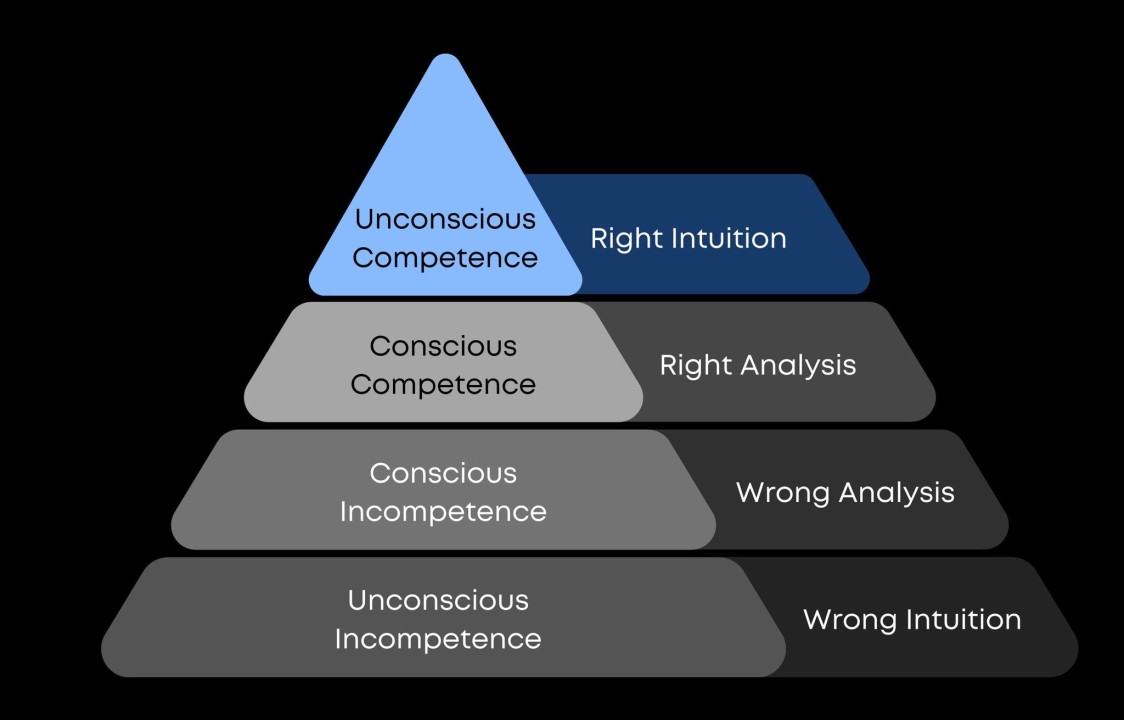

I’m not trying to get down on the OP here. They are obviously a beginner, and they are in the first stage of the “Hierarchy of Competence”: “Unconscious Incompetence”:

Basically, this just means that they don’t know what they don’t know. This is what it means to be a beginner, you make beginner mistakes and your intuition about how things work and what constitutes a good solution are often just plain wrong.

The idea that you can save a meaningful amount of memory by utilizing a screen Node as a data store is wrong. But even more important, the idea of using a screen Node to store data is just something that more experienced JavaFX programmers wouldn’t even think about doing.

James_D sums it up perfectly:

“I should’ve made 2D matrix and connect it with grid pane” Yes, basically something along those lines. For a game or simulation (or any UI application, but those seem to be more applicable here) it’s always a good plan to first write it from the data perspective only, so you can drive it just from code, and then to add the UI on top of that once it’s working. The memory consumed by the data representation is basically negligible compared to the memory consumed by the UI, so that should not be a concern.

The “grid-lines as a child of the GridPane” concept is interesting. Hey! I didn’t know this either. But, ultimately, it’s just that, “interesting”, but not particularly useful.

If this was school assignment, and this approach was submitted to me to mark, I would deem it “non-functional” and give it a “D”. Relying on the private internal implementation of a library is simply a recipe for disaster.

About that “2D Matrix”

Let’s look at the idea that the OP had for reworking the architecture:

Okay so I should’ve made 2D matrix and connect it with grid pane, and work with matrix right?

Pretty much every beginner looking at creating some grid based application or game comes up with the idea of some data structure like Cell[][]. That’s what the beginners intuition tells them to do.

But is a 2D array really the best way to structure this?

I don’t think so. What’s the advantage to it? Just about the only thing that I can see is that you get sub-nanosecond random access to any Cell given it’s coordinates. That’s it.

But what’s wrong with Cell[][]?

First of all, you end up with nested row/column loops all over the application. Even in the example code, above, there’s two of the darned things - and that’s only 30 lines of code.

Secondly, you end up doing row and column math all the time. “Down” math is row = row + 1 and column = column. But then you have to check to make sure that you haven’t end out of bounds. Is the new row bigger than maxRows? How do you handle that?

Thirdly - and this is where I think it starts to get to the “Right Intuition” of “Unconscious Competence” - Cell[][] isn’t a very “Java” approach.

Let’s look at this some more…

The Java Way of Doing This

A fundamental concept in Java is the idea of “encapsulation” - data and the code that deals that data are bundled together, and very often the data is not exposed to the outside world. Cell[][] simply violates that idea.

Normally, when I see Cell[][] implemented, Cell does not contain the location coordinates. Presumably, beginners feel that having row and column fields inside Cell is a waste of memory since it’s already stored in the indices to Cell[][]. The result is that Cell no longer owns its own data, and you cannot have methods in Cell that deal with that data and potentially hide it from the outside world.

The truth is that most applications don’t actually need to know the Cell coordinates for most logic. Finding adjacent Cells is often much more important. If a Cell can tell you which Cell is “down” from it, that’s usually good enough. How the Cell determines “down” isn’t important to your application logic - just that it does it.

What’s really important is that getting the Cell coordinates is almost never the goal of any operation. The only reason you ever want the Cell coordinates is to get that Cell. So if your Cells themselves can pass you Cells, then you never need the coordinates.

Think about this:

Let’s say you’re writing some sort of chess game, and you need all of the possible moves for a bishop, which is the diagonals from its current square (Cell). What do you want, a list of coordinates for those Cells, or a list of the Cells? So if a Cell can give you the Cell “up to the right” (or whatever diagonal direction you want), then you can ask that Cell for it’s neighbour “up to the right”, until the answer comes back EMPTY, at which point you’ve hit the edge of the board.

Now think about how you might implement this.

Cells and a Cell Factory

What I would probably do is have fields for the adjacent Cells and they would be nullable in Kotlin or Optional in Java:

class Cell<T>(val column: Int, val row: Int, val contents: T) {

var north: Cell<T>? = null

var south: Cell<T>? = null

var east: Cell<T>? = null

var west: Cell<T>? = null

val northEast: Cell<T>?

get() = north?.east

val northWest: Cell<T>?

get() = north?.west

val southEast: Cell<T>?

get() = south?.east

val southWest: Cell<T>?

get() = south?.west

fun adjacentCells() = listOfNotNull(north, south, east, west)

fun diagonalCells() = listOfNotNull(northEast, northWest, southEast, southWest)

fun touchingCells() = listOf(adjacentCells(), diagonalCells())

}

I’ve chosen to make my Cell class generic, since the topography of the Cell is independent of whatever you are holding in it. So we have field called contents and it will be of whatever type we specify with Cell<T>.

In Kotlin, you can have properties (which are a bit like fields in Java, but more sophisticated) that are derived from other properties. In this case we have the diagonally adjacent Cells accessed through read-only properties that are based on Cells that are at the north, south, east and west positions. The formula for northEast is:

get() = north?.east

The ?. operator is very much like Optional.map(). If north is Null, then the result is Null, otherwise it will return the east field (which might also be Null) of that Cell in the north location. The result is nullable, which, once again, is somewhat equivalent to Optional in Java.

The other three methods return lists of neighbour Cells that really are there, due to the listOfNotNull() function. This means that they return List<Cell<T>>, not a List<Cell<T>?>, so you can use the List items as Cell.

Now, on to creating Cells:

class CellFactory<T>(private val maxColumns: Int, private val maxRows: Int, contentSupplier: () -> T) {

private var cells: Array<Array<Cell<T>>> = Array(maxColumns) { column ->

Array(maxRows) { row ->

Cell(column, row, contentSupplier.invoke())

}

}

init {

getCells().forEach { cell ->

cell.north = getCell(cell.column, cell.row - 1)

cell.south = getCell(cell.column, cell.row + 1)

cell.east = getCell(cell.column + 1, cell.row)

cell.west = getCell(cell.column - 1, cell.row)

}

}

fun getCells() = cells.flatten()

private fun getCell(column: Int, row: Int): Cell<T>? =

if ((column >= 0) && (column < maxColumns) && (row >= 0) && (row < maxRows)) cells[column][row] else null

}

This class is, as the name implies, just a factory for creating a collection of Cell. It has one field, and that’s a two dimensional array. You need to provide a Supplier (which in Kotlin is () -> T) to generate the contents for each Cell when it’s instantiated. This could be a BiConsumer taking column and row if you want, but I didn’t need it for this.

The init{} block does the work of the Cell math to initialize the non-diagonal neighbours of each Cell. This has to be done as a separate, second step because any particular Cell will probably be instantiated before all of its neighbours are instantiated (unless it’s in the bottom right corner), so we cannot get references to them.

The function getCell() handles the boundary cases, when the indexes are less than zero or greater than the dimensions of the matrix.

Finally getCells() is the only public function, and it returns a List<Cell<T>>. This means that the calling class won’t even have access to the two dimensional matrix - we don’t need it any more.

An Application Using These Cells

I used a Model-View-Controller-Interactor (MVCI) framework to build an application that works with this design of Cell.

Let’s look at the Model first:

class Model() {

val cells: ObservableList<Cell<ObjectProperty<Color>>> = FXCollections.observableArrayList()

}

This looks a little messy because of all of the nested generic references. Reading from the inside out; our actual data is Color and it’s in an ObjectProperty so that we can bind it to our View Properties. So ObjectProperty<Color> is the generic type of our Cells. Finally, all of the Cells are held in an ObservableList, and that’s all we have in our application Model.

Now the Controller:

class Controller() {

private val model = Model()

private val interactor = Interactor(model)

private val viewBuilder = ViewBuilder(model) { interactor.handleCellAction(it) }

fun getView() = viewBuilder.build()

}

This is very vanilla. The Controller instantiates the other three components and then provides a getView() to serve up the layout to the application. We’re passing a Consumer<Cell> to our ViewBuilder as a constructor parameter that invokes a method in the Interactor.

And the Interactor:

class Interactor(private val model: Model) {

init {

model.cells += CellFactory(10, 10, this::colourGenerator).getCells()

}

private fun colourGenerator(): ObjectProperty<Color> {

val colors = listOf(Color.RED, Color.BLUE, Color.YELLOW, Color.GREEN, Color.ORANGE)

return SimpleObjectProperty(colors[Random.nextInt(5)])

}

fun handleCellAction(cell: Cell<ObjectProperty<Color>>) {

cell.contents.value = Color.BLACK

cell.diagonalCells().forEach { it.contents.value = Color.BLACK }

}

}

The init{} method creates a CellFactory and then puts the resulting list of Cells in the ObservableList in our Model. The Supplier for the CellFactory creates ObjectProperty<Color> with one of 5 random colours.

Kotlin doesn’t require use to declare the CellFactory as CellFactory<ObjectProperty<Color>>, because it can figure that out by the return type of the Supplier.

We’ll come back to the handleCellAction() method after we look at the ViewBuilder:

class ViewBuilder(private val model: Model, private val clickHandler: (Cell<ObjectProperty<Color>>) -> Unit) :

Builder<Region> {

override fun build(): Region = Pane().apply {

model.cells.forEach { cell ->

children += Rectangle(48.0, 48.0).apply {

fillProperty().bind(cell.contents)

x = (cell.column * 50.0) + 1

y = (cell.row * 50.0) + 1

onMouseClicked = EventHandler { clickHandler(cell) }

}

}

}

}

This will create a Pane and then populate it with a bunch of Rectangle. Each Rectangle has its FillProperty bound to the ObjectProperty<Color> in a Cell. The position of each Rectangle is based on the column and row of a Cell.

The ViewBuilder is responsible for determining:

- The shape of the GUI elements - in this case, a

Rectangle - The size of the GUI elements - in this case, 48px square.

- The location of the GUI elements - in this case, in a grid using x & y translations.

Some things to note about this:

- This is the only place in the entire application that actually uses the

columnandrowproperties ofCelloutside theCellFactory. It needs to do this because has to be able to determine the topography of the GUI in order to draw it. - This loop doesn’t use nested loops for column and row. Who cares what order the

Rectanglesare drawn? EachCellcan be treated on its own as a self-contained entity. The ViewBuilder knows where to put it with any reference to any otherCells. - The ViewBuilder has no reference anywhere to

maxRowsormaxColumns. It doesn’t need them.

These last two points really turn the GUI creation upside down. It’s data driven: Rather than looking for the correct piece of data to match with a GUI element that we’re drawing, we create the GUI elements for each piece of data as we iterate through the data. If our application logic meant that we wanted to leave holes in the grid, then we would simply remove those Cells from the Model and the ViewBuilder wouldn’t create the Rectangles for them. The ViewBuilder wouldn’t have any logic to leave holes, they’d just happen.

In our GUI, each Rectangle has two relationships back to the Cell that caused it to be created. One is the binding to the FillProperty of the Rectangle and the other is the OnMouseClicked handler. This handler invokes the Consumer passed in via the constructor, and it simply passes the related Cell to that Consumer.

Now let’s think about the click handler. Through the Controller, we’re going to pass the Cell back to the handleCellAction() method in the Interactor. Here it is again:

fun handleCellAction(cell: Cell<ObjectProperty<Color>>) {

cell.contents.value = Color.BLACK

cell.diagonalCells().forEach { it.contents.value = Color.BLACK }

}

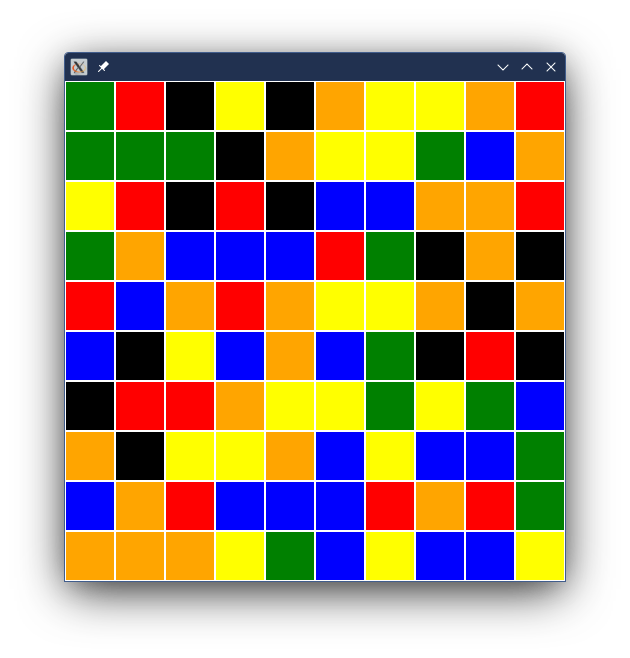

This turns the Cell black, and then turns all of the Cells at its diagonal corners black as well.

Running the Application

Here’s the Application:

class CellApplication : Application() {

override fun start(stage: Stage) {

val controller = Controller()

stage.scene = Scene(controller.getView(), 500.0, 500.0)

stage.show()

}

}

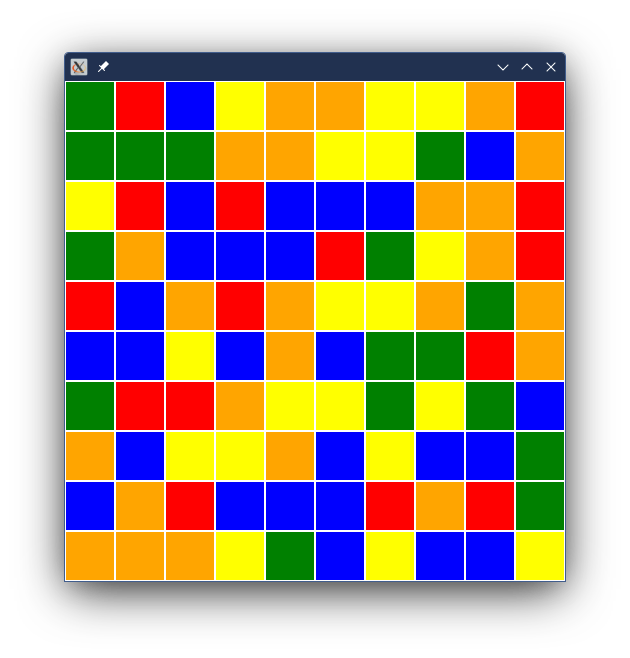

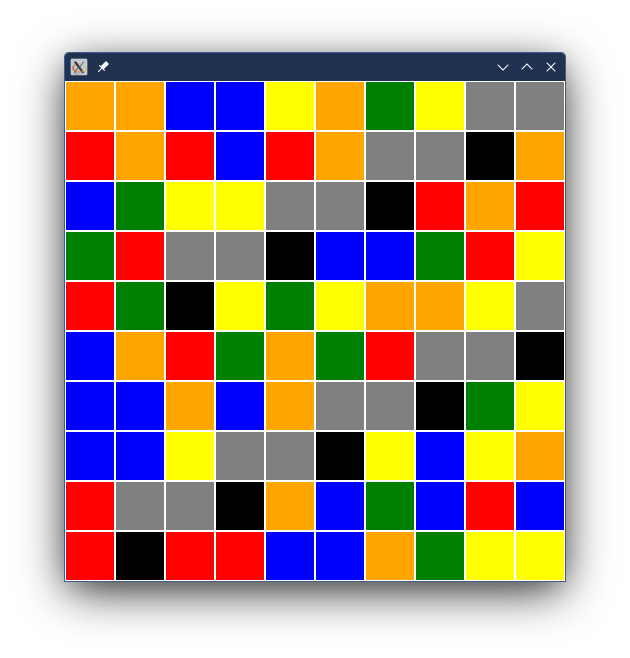

And this is what it looks like in action:

Once you’ve clicked on a few Rectangles it looks like this:

Some Variations

It wouldn’t be unfair to say, “Hey! This still uses a two dimensional matrix.” So let’s take a look at that, and create a CellFactory that doesn’t use a two dimensional array:

class CellFactory<T>(private val maxColumns: Int, private val maxRows: Int, contentSupplier: () -> T) {

private var cells: List<Cell<T>> = mutableListOf()

init {

for (column in 0..maxColumns) {

for (row in 0..maxRows) {

cells += Cell(column, row, contentSupplier())

}

}

cells.forEach { cell ->

cell.north = getCell(cell.column, cell.row - 1)

cell.south = getCell(cell.column, cell.row + 1)

cell.east = getCell(cell.column + 1, cell.row)

cell.west = getCell(cell.column - 1, cell.row)

}

}

fun getCells(): List<Cell<T>> = cells.toList()

private fun getCell(column: Int, row: Int): Cell<T>? = try {

cells.first { cell -> (cell.column == column) && (cell.row == row) }

} catch (e: NoSuchElementException) {

null

}

}

Here we’ve just used a list to store all of the Cells. We still need the two nested loops to handle the initial creation of the Cells with the row and column values. Instead of using the [][] operator to look up a Cell by column and row, we just use a filter on the List. The List.first() function throws an exception if it cannot find anything that meets the predicate, so we catch that and just return a Null instead.

This version works. It may run a nanosecond slower than the original version, but unless you have a zillion Cells, it’s not going to matter. But that does NOT mean that it’s as good as the first version. On one hand, it avoids the boundary checking in getCell(), but the original version is more direct, and therefore might be easier to understand and maintain.

In either version, you could change the name to something like CellSet and make CellSet.getCell() public. This would allow for random access to individual Cells while still keeping the underlying data structure private.

This design makes the application Cell centric, instead of grid-centric. This means that operations are likely going to be recursive in nature. Let’s add a function to Cell to generate a List of Cells that are in a line in any direction (up, down, left, right or any of the 4 diagonals):

fun row(function: (Cell<T>) -> Cell<T>?): List<Cell<T>> =

function(this)?.run { listOf(this@Cell) + this.row(function) } ?: listOf(this)

This is a recursive function with a closure. The function tells how to find the next Cell in the series. If the next Cell in the series is Null, then we’ve hit the edge of the grid, in which case we just return the current Cell as the only member of a List. Each Cell up the recursion chain will add itself to the List that it gets back from the Cell down the recursion chain.

If we go back to the handleCellAction() method in the Interactor and change it to use this new function:

fun handleCellAction(cell: Cell<ObjectProperty<Color>>) {

cell.contents.value = Color.BLACK

cell.row { it.northEast }.forEach { it.contents.value = Color.BLACK }

}

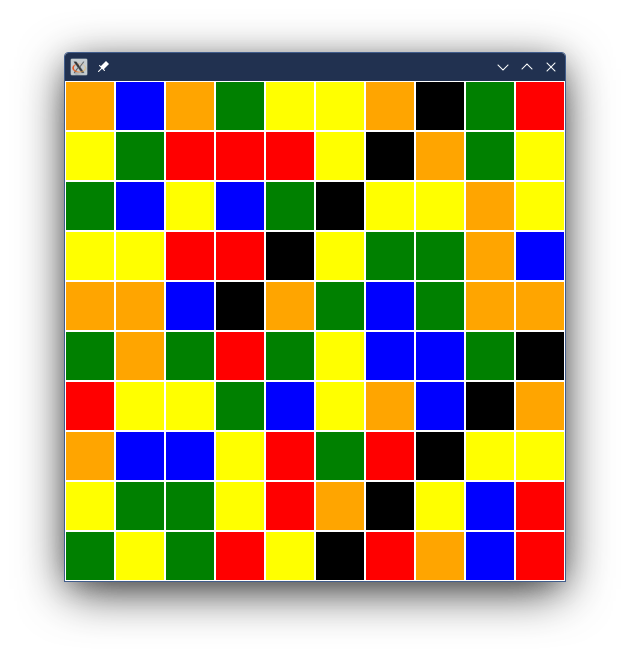

We now get black diagonals when we click on a Rectangle:

Let’s say that we’re doing some kind of Chess based game and we want to show knight moves from a location, indicating the shape of the knight’s movement (kind of an “L” shape). We could do something like this:

fun handleCellAction(cell: Cell<ObjectProperty<Color>>) {

cell.contents.value = Color.BLACK

cell.row { it.north?.east?.east }.forEach { it.contents.value = Color.BLACK }

cell.row { it.north?.east?.east }.mapNotNull { it.north }.forEach { it.contents.value = Color.GRAY }

cell.row { it.north?.east?.east }.mapNotNull { it.north?.east }.forEach { it.contents.value = Color.GRAY }

}

The first call to Cell.row() (which isn’t really generating a “row” of Cells any more), returns the squares that the knight would move to. The second call yields the first intermediate Cell in the “L” shape, and the third call yields the second intermediate Cell. These intermediate Cells are shaded gray.

]

]

And yes, things are getting a bit confused with the riot of colours going on now, but you should be able to see the pattern.

Conclusion

If you go back and count, you’ll find that this example application has a grand total of about 100 lines of code. Cell and CellFactory are the biggest classes, at about 20 lines each, and all the others are less than 15 lines. The longest function in the application is the ViewBuilder.build() at 10 lines long - if you include the 3 } lines at the end. It’s pretty hard to get lost in a 100 line application broken down into <10 line functions.

Even with this little code, this demo application does a lot. Well…maybe not “a lot”, but certainly more than you’d expect.

But is this “Right”, or even “Better”?

I think we can all agree that using the GridPane to store the location information about the data is actually wrong. But what about building the application around a data model consisting of a two dimensional array? Is that wrong? Is it even worse?

Occasionally, I see applications where a programmer has chosen to create Map<String, Int> because they would rather not “clutter up” their application with:

class MyClass() {

val name: String

val amount: Int

}

They’ll use a Map even when they really aren’t interested in fast, random access to particular entries based on name. What they want is the Entry<String, Int> because it ties those two values together without all the “trouble” of creating a dedicated class for it.

If you have a Map and the only thing you’re ever doing is iterating over Map.entrySet(), then you probably shouldn’t be using a Map.

Personally, if I did need that fast, random access, I’d still create the class and then use a Map<String, MyClass>. Beginners usually choke over the idea of having a class with just two fields, and then using one of those fields as the key to a Map. Something about wastage, I think.

The idea of using a two dimensional array is just about the same thing. The array “ties together” the x/y location with the data without going through the “trouble” of creating a class for it.

But I think there’s more to it than just that…

There’s the naive idea that a two dimensional array mirrors the reality of the application - that it’s essentially a two dimensional grid and the mechanics of the application and the resulting implementation should revolve around that topography.

But the problem with that approach is that it saddles you with the need to deal with that matrix in everything that you do.

Yes! But is that “wrong”??? Is it even “worse”????

I think that, without a doubt, taking an approach that increases the complexity of your application can be classified as “worse”.

It’s often far worse than it at first appears. Take this sample application as an example - getting rid of the two dimensional array results in a completely different view of the application as it’s no longer grid-centric, but cell-centric, and all of the logic changes. Although it’s hard to see it from such a small application, this change of perspective actually has an enormous potential to simplify virtually every aspect of how the application works.

Personally, I have the attitude that if I’ve written something and I see (or someone shows me) a better way to do it, then my solution is “wrong”.

In any discussion of these issues, however, someone will eventually say something to the effect of (and maybe you’re thinking it too):

“That’s just your way of doing it and it’s all a matter of style. This other way runs and gets the correct answer too; it might not be your way but it’s just as good”.

And now we’re back where we started: A program can run and get the correct answer, and yet still be “wrong”.

Outside of a school project, running and getting the correct answer isn’t the goal itself, it’s just a necessary requirement that has to be met on the way to the goal. In the real world, applications often need to written so that they can be understood, maintained and enhanced over an extended period of time by a variety of developers. The actual goal is to get the correct answer and support future maintenance and enhancement.