Introduction - Why Use a Framework?

Frameworks are all about organizing your application so that it will be easy to maintain, enhance and expand over time.

If your application is going to actually “do something” it will probably need to interact with the world outside your application. This might just be the local file system, but it might be a local database, or a remote database, another local application or REST API for some service anywhere on the Web. In any event, you need to organize your application so that you don’t have your screen layout muddled up with business logic and calls to external databases and services.

There are a number of frameworks to choose from, but they are all designed to keep your business logic out of your layouts, and your layouts out of your business logic. If they are done right, then your layouts and your business logic can connect without either one knowing anything at all about the other.

This article is about my own framework, “Model-View-Controller-Interactor”, which works in a manner very similar to the other framemworks that you’ll hear about, but is fine tuned to work with JavaFX when it’s used to create “Reactive” GUI applications.

What’s Wrong With the Others?

This is a quick guide, so I’m not going to go into a deep description of the other frameworks or how they work. But I will explain why I feel they fall short when building Reactive applications with JavaFX:

-

Model-View-Presenter (MVP)

The problem with MVP is that the View is stripped down to nothing more than layout and styling, leaving all other aspects of the GUI to be handled by the Presenter. This requires a level of coupling between the View and the Presenter that is so tight that they might as well be considered to be a single component. The Presenter then becomes a “god class”. I’m not sure that anybody uses MVP any more. -

Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM)

MVVM looks like a much better fit for Reactive JavaFX because it specifically allows for binding between the Presentation Model and the View. However, the ViewModel isn’t allowed to see the Domain Objects and the Model isn’t allowed to see Presentation Model and the result is complications passing data between the ViewModel and the Model. The coupling is loose, but it becomes a problem itself because it can be very complicated to work around. -

Model-View-Controller (MVC)

MVC solves many of the issues with MVVM because the Presentation Model is part of the Model. However, MVC specifically exposes the Model (and, therefore, the Presentation Model) to the View in a “read-only” mode. This means thatPropertiesin the Model cannot be bound bidirectionally to thePropertiesof theNodesin the View and updates must be passed through the Controller to the Model.

What is Model-View-Controller-Interactor?

MVCI solves the problems of these other frameworks by taking MVC and splitting the Model into two parts: the Presentation Model (just called the “Model” in this framework) and the “Interactor”. This new Model is simple a POJO composed of JavaFX Observable objects and lists, and the other three components all have read and write access to it.

The result is something that is instantly simple and easy to integrate with Reactive JavaFX. Properties of the Nodes in the View can be bound in either direction to the elements of the Model. This means that the Model is truly a data representation of the “state” of the GUI at all times. At the other end of the framework, all of the business logic is contained and isolated within the Interactor, which also is the only component that can access external services, applications and databases.

This fulfils the purpose of the framework. Business logic, application connective tissue and GUI design are all isolated from each other and very loosely coupled. You’ll find that this structure is a natural fit for Reactive JavaFX and takes very little effort to implement.

The Components of MVCI

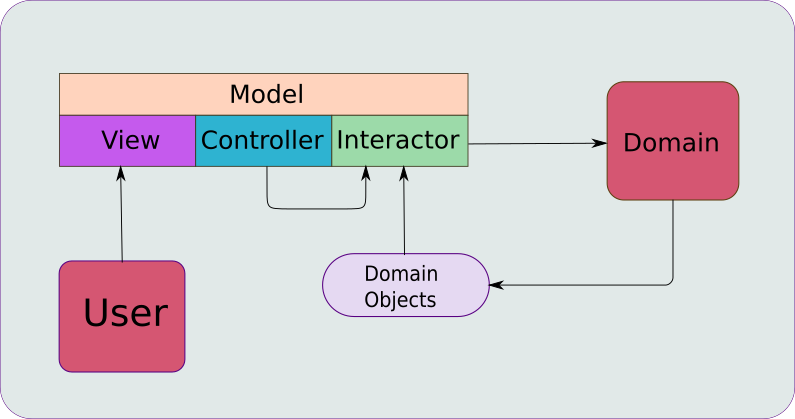

This diagram shows the components of MVCI in relation to each other and external elements:

Let’s take a look at the four components of MVCI and see what they are how they work together.

The Model

The Model is just a bunch of data. But it’s data stored in JavaFX Observable objects (typically Properties), and ObservableLists. The intention is that the Interactor will treat the Observables simply as wrappers around data, ignoring their Observable nature (for the most part). At the other end, the View treats the Model as a collection of ObservableVales that it will treat only as Observable. This means that the View primarily interacts with the Model through Bindings, and perhaps Subscriptions or Listeners.

The Controller

The Controller is the connective tissue of the framework. It instantiates all the other components, and it handles anything involving threading (which becomes important when you need to deal with long or blocking processes off the FXAT). It also contains any links back to other MVCI frameworks in your application, usually through shared Model elements. Typically, you will initiate an MVCI framework by instantiating the Controller, and it will bootstrap itself through it’s constructor code.

The Interactor

Here’s where the business logic resides, and the calls to your external services, databases and applications. It’s also the only place that you’ll find “Domain Objects”. Domain Objects are the classes that hold the data that are returned from (and are sent to) your “Services” and they are completely foreign to your View and your Controller.

The View and the ViewBuilder

The View is a fully functioning JavaFX Node subclass that can be added to the SceneGraph. It handles all of the display, and any direct interaction with the user.

The preferred way to create a View is the “configuration” of an existing Node sub-class via a Builder. Happily, JavaFX has an interface called Builder<T> with a single method called build(). If you follow this approach, and it’s usually the correct one, then you won’t have a View class in your framework, but you’ll have a ViewBuilder which implements Builder<Region>.

What Goes Where?

One of the nice things about MVCI is that all of the decisions about where to put your code are straight-forward and easy to resolve. Let’s look at some of the most important items:

Business Logic

This is the question to ask first: “Is this business logic?” If your application isn’t a business application, then substitute some other term like, “game logic”. You get the idea.

If the answer is “YES”, then it goes in the Interactor. No exceptions.

Presentation

Another question to ask is whether the code deals solely with how the data is presented to the user. That “solely” is interpreted very narrowly and if the answer is “YES”, then it goes in the View. Is something going to be displayed in a particular colour? That colour choice is probably solely presentation and belongs in the View. However, if that colour choice is based on something that smells like business logic, then it’s not solely presentation. You’ll need to split out the business logic, put that part in the Interactor and use the results of that to determine the actual colour to be used in the View.

For example, imagine you have a list of grocery items and you want veggies in one colour, and fruit in another, and dairy in another colour. If your list is just; bananas, carrots, apples, tomatoes and milk, then you’ll have a problem determining the colours in the View. What’s a “tomato”? Is it a fruit, a veggie or dairy? That’s a business logic decision, and cannot be made in the View. Update your Model such that the list also contains the type, and then populate it accordingly from the Interactor. Now you’ll get; bananas(fruit), carrots(veggie), apples(fruit), tomatoes(technically fruit, but used like a veggie), and milk(dairy). In your View, you look at the types and determine the colour based on that, because now that is solely a presentation decision.

Domain Logic

It’s important to understand that “Business Logic”, as it is used above actually means, “business logic specific to this MVCI construct”. This does not include calling external API’s or parsing JSON data. Things like that belong in a layer below your Interactor that holds the “Domain”.

Let’s take a look at the fruit and veggie example above. If your list of items is coming from a database somewhere, you are NOT going to put SQL statements or any equivalent in your Interactor. Create a GroceryListService that does the database access, then parses the resultant JSON data and creates a list of GroceryItem which probably has at least name and quantity. GroceryItem is your domain object, and that list is passed back to your Interactor.

But what about the type?

Let’s say that you’ve found some web service like Chomp that can give you information about grocery items, (full disclosure, Chomp doesn’t seem to tell you what department stuff is in) and you are going to use it to determine fruit, veggie or dairy. The code that contains the API calls and the JSON parsing for that function also goes into a service. However, the code that loops through your list of grocery items, calls the service to find out what type of item it is, and then integrates the two together into the Model is business logic for this MVCI construct and goes in the Interactor.

Presentation Data

The Model contains just “Presentation Data”. In other words, every element is something that is potentially used directly by both the View and the Interactor. Another way that you can think about it is that the “Presentation Data” represents the “State” of your entire MVCI construct. Because the View and the Model are connected to each other through Bindings, any relevant changes to your View are going to be mirrored in your Model and they are going to be immediately visible and available to the Interactor. At the same time, any changes to the Model made by the business logic in the Interactor are going to be instantly reflected in the View.

An Example

The best way to understand this is to see it in code. So we’ll build that grocery list application to see how it works…

The Application

class MvciApplication : Application() {

override fun start(stage: Stage) {

stage.scene = Scene(Controller().getView(), 600.0, 400.0)

stage.show()

}

}

fun main() = Application.launch(MvciApplication::class.java)

The most important take-away here is the way that the Controller is instantiated and then simply used to retrieve the View so that it can be placed in the Scene.

The perspective that you need to have is that the View, which is just some sort of Node subclass, is the important product of the Controller from a viewpoint outside the MVCI framework. This is the thing that you are going to stick into your GUI. In this case we’re putting in as the root element of a Scene, but it could become the child of some other layout class. It will still work.

The Controller

The rough skeleton for a Controller is always something like this:

class Controller {

private val model= Model()

private val interactor = Interactor(model)

private val viewBuilder:Builder<Region> = ViewBuilder(model)

fun getView() : Region = viewBuilder.build()

}

But we are also going to be doing some database lookups in our application, so we’ll need to use Task to handle the threading and call the Interactor methods to do the work:

class Controller {

private val model = Model()

private val interactor = Interactor(model)

private val viewBuilder: Builder<Region> = ViewBuilder(model) { fetchList() }

private fun fetchList() {

Thread(object : Task<List<GroceryItem>>() {

override fun call() = interactor.getList()

}.apply { setOnSucceeded { _ -> interactor.updateModelAfterFetch(get()) } }).apply {

isDaemon = true

start()

}

}

fun getView(): Region = viewBuilder.build()

}

The Model

Our Model is going to have three classes, one to hold the actual grocery items and another to hold (at least) a list of those items. The final class is an Enum to hold the departments:

class Model {

val listName: StringProperty = SimpleStringProperty("")

val groceryList: ObservableList<GroceryModel> = FXCollections.observableArrayList()

}

class GroceryItem {

val name :StringProperty = SimpleStringProperty("")

val quantity: ObjectProperty<Int> = SimpleObjectProperty(0)

val department: ObjectProperty<Department> = SimpleObjectProperty()

}

enum class Department {

DAIRY, FRUITS, VEGGIES, MEATS, BAKERY;

}

The Enum class Department is more of a utility class than part of the Presentation Model, as it’s used in the Domain Objects as well.

The ViewBuilder

Our ViewBuilder is just a class that implemnents Builder<Region>. As is often the case with “top-level” Views, it’s best to return a BorderPane:

class ViewBuilder(private val model: Model, private val listFetcher: () -> Unit) : Builder<Region> {

override fun build(): Region = BorderPane().apply {

center = createTable()

bottom = createLookup()

padding = Insets(15.0)

}

private fun createLookup(): Region = HBox(10.0).apply {

children += Label("List Name:")

children += TextField().apply {

textProperty().bindBidirectional(model.listName)

}

children += Button("Fetch").apply {

setOnAction { listFetcher.invoke() }

}

padding = Insets(5.0)

}

private fun createTable(): Node = TableView<GroceryModel>().apply {

columns += TableColumn<GroceryModel, String>("Item Name").apply {

setCellValueFactory { p -> p.value.name }

}

columns += TableColumn<GroceryModel, Department>("Department").apply {

setCellValueFactory { p -> p.value.department }

}

columns += TableColumn<GroceryModel, Int>("Quantity").apply {

setCellValueFactory { p -> p.value.quantity }

}

items = model.groceryList

columnResizePolicy = TableView.CONSTRAINED_RESIZE_POLICY_LAST_COLUMN

}

}

The View is just a BorderPane with a TableView in the centre and an HBox holding the “Lookup” controls in the bottom. You can see how the input TextField is bound to Model.listName bidirectionally, and the ObservableList held in Model.groceryList becomes the items in the TableView.

We’ll talk about this some more later, but note that the EventHandler on the Button invokes the Runnable passed from the Controller as listFetcher.

The Interactor

class Interactor(private val model: Model) {

private val listService = GroceryListService()

fun getList(): List<GroceryItem> {

return if (model.listName.value.isEmpty()) {

listService.fetchList("DEFAULT")

} else {

listService.fetchList(model.listName.value)

}

}

fun updateModelAfterFetch(groceries: List<GroceryItem>) {

model.groceryList.setAll(groceries.map { createGroceryModel(it) })

}

private fun createGroceryModel(groceryItem: GroceryItem) = GroceryModel().apply {

name.value = groceryItem.itemName

department.value = groceryItem.theDepartment

quantity.value = groceryItem.howMany

}

}

Things to note about the Interactor:

-

The function

getList()contains code to handle a blank list name.

This is because the manner that an empty list name is dealt with is something that is very specific to this application. It’s not defined at the service level. Some other application might want to return an empty list, or maybe generate an error warning. -

The Interactor knows about

GroceryItem, which is a “Domain Object”. There are no usages ofGroceryItemin the Controller, Model or View. -

The Interactor does not compose REST calls, or SQL statements. It simply asks the Service to get the information, without any knowledge of how it will do it.

-

The Interactor takes the Domain Objects from the Service, and converts them into Presentation Model objects, which are then put into the Model.

The Service Layer (Domain) Elements

We are just going to simulate the operation of a Service here, since we’re not going to create a database or access any remote web API’s to retrieve data:

class GroceryListService {

fun fetchList(listName: String): List<GroceryItem> {

Thread.sleep(2000)

return listOf(

GroceryItem("Celery", Department.VEGGIES, 10),

GroceryItem("Milk", Department.DAIRY, 4),

GroceryItem("Grapes", Department.FRUITS, 230)

)

}

}

data class GroceryItem(val itemName: String, val theDepartment: Department, val howMany: Int)

We’ve also defined our Domain Object, GroceryItem here. The most important point is that GroceryItem is NOT just a POJO representation of JSON data from some external source. It might actually be created that way, this definition of GroceryItem is related to whatever layour of our Service interacts with its client applications. The Service might be accessed by dozen of different screens in our application, and they may or may not expect to send or receive GroceryItem to or from the Service. But they all know how to deal with GroceryItem if they get it.

Some More About this Example

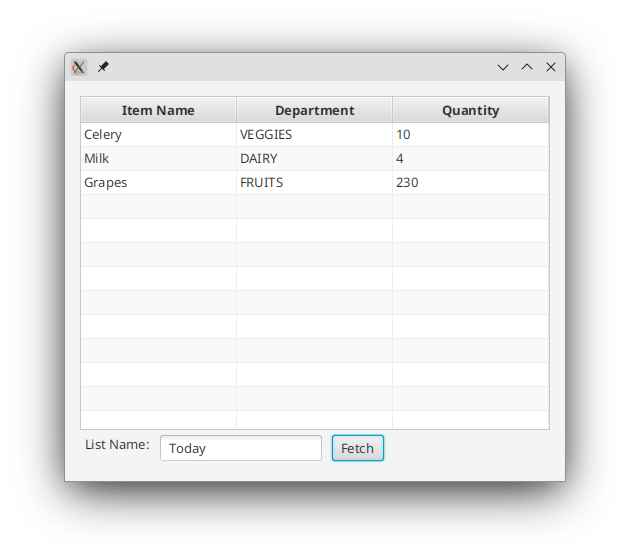

This application will run. It looks like this:

All told, there’s about 100 lines of code in this example (I counted), and this is way more complete than any example you’ll find for MVC or MVVM out there on the web. Let’s look at what this does:

- It actually runs.

- It handles background threading via

Task - It has an actual Service layer.

- The Service layer simulates external services completely hidden from the MVCI framework.

- It has some business logic.

- The MVCI framework part of this example is 100% operational.

The only simulated part is the Service layer which is external to the framework. This means that you can absolutely test this framework without connecting to an actual external database or REST API.

Coupling and Dependencies in MVCI

This is quick guide, so we won’t have a lot of theory. However, the main point of any framework is to limit and control the coupling in your application. So it’s important to understand how MVCI does this, and where the depencies exist.

MVCI is Almost a Closed System

The first thing that you need to understand is that the primary method of all coupling is via public methods (or public fields). Every time that you introduce a public method, you’ve tied yourself down just a little bit more. A class with no public methods cannot be coupled to (or depended on).

In MVCI the Model, the Interactor and the ViewBuilder are all private to the framework. There’s no way for any outside class to get a reference to any of these three classes. That means that there’s no way that any outside class can call any public methods in these three classes, making them effectively private to the framework.

There are exactly two truly public methods in MVCI, and they are both in the Controller. The first is the constructor for the Controller, which has to be public in order to create the framework in an application. It is possible to create dependencies here by specifying constructor parameters.

The second externally visible method is the Controller.getView() method, which returns the View, which is always just a vanilla JavaFX Region or Region subclass.

This is literally the bare minimum coupling that you can have and still have a functional framework.

Coupling Through the Model

This is the key element of coupling in MVCI. Every other component can see the Model and depends on its visible structure.

Clearly, therefore, any visible changes to the Model have the potential to break some other component of the framework. At the same time, changes can often be made to the other components without affecting any other part as long as they continue to work with the Model without changing its structure.

In practice, this gives a fair degree of latitude. Internal changes can be made to the Model, as long as the public methods remain unchanged.

Coupling Between the Controller and the ViewBuilder

The View with JavaFX is almost always a Region or a standard subclass of Region, and will only have the public methods of Region The result is that there’s no coupling introduced via the View itself.

However, the ViewBuilder is custom but you can see that it is instantiated as Builder<Region>, which has only one public method, Builder.build().

At first glance, it would seem that the View needs to have dependencies on the Controller in order to invoke activity in the Interactor. To avoid this two techniques are used; “Dependency Inversion” (or “Inversion of Control”, IoC), and “Dependecy Injection”.

This is done via the constructor of the ViewBuilder. In the example it’s: ViewBuilder(private val model: Model, private val listFetcher: () -> Unit). It’s the second parameter that does the work, listFetcher : () -> Unit, which is the Kotlin equivalent of a Runnable, but we could have specified a Consumer or a BiConsumer here.

The important thing is that listFetcher is a general purpose functional interface that “inverts” the dependency. Now, instead of the ViewBuilder needing a reference to the Controller in order to call one of its public methods, the Controller needs to know what functional element it needs to pass to the ViewBuider.

Essentially the ViewBuilder, by having this constructor parameter, is saying, “Anyone can instantiate me, but you need to give me this functional element in order to do so”. That functional element has to implement the specified interface, but there’s no knowledged passed on to the ViewBuilder about what it does or how it does it.

And yes, the Controller has to supply something that responds meaningfully to the context in the View is going to invoke it. But, at the end of it all, the View/ViewBuilder knows zero about the Controller, and the Controller only knows that the ViewBuilder is a Builder<Region> and requires a particular functional element as a constructor parameter.

Coupling Between the Controller and the Interactor

This is the biggest coupling after the Model itself.

In order to work, the Interactor needs to expose a number of public methods that can be called from the Controller. In the example we have Interactor.getList() and Interactor.updateModelAfterFetch().

You should note, however, that all of the coupling inside MVCI is outwards from the Controller. The Controller knows what parameters to pass to the ViewBuilder, and it knows which methods to call in the Interactor. Since the Controller instantiates the other elements, it also already has to know their types.

On the other side, neither the ViewBuilder nor the Interactor have any knowledge at all about even the existence of the Controller or each other.

When you are building your own applications, you want to keep things this way. Try to stick to these “rules”:

- Don’t add public methods to the Controller, as they will become visible outside the framework and become points for coupling.

- Don’t pass references to the Controller to the ViewBuilder or the Interactor.

- Don’t pass references to each other between the Interactor and the ViewBuilder.

Coupling Between the Interactor and the Services

The last piece of coupling is between the Interactor and the Services it will use. Once again, this coupling is unavoidable if you want you application to actually “do” something. But you can keep it strictly one-way. That is to say, the Interactor will have dependencies on its Services, but the Services won’t have any dependencies on the Interactor.

There are two main points of coupling:

-

The “Domain Objects”

Clearly the structure of the Domain Objects is a major dependency in this part of the application. However, it’s also the main way of controlling the coupling, as it isolates the Interactor from changes in the external services. Even if a database structure is radically altered, it remains the Services’ responsibility to continue to return valid Domain Objects in the same structure as always. -

The Services’ APIs

The public methods of the Service are the other coupling at this level. There’s nothing that says that a Service has to be designed for use by multiple MVCI frameworks. You can have a Service specifically tailored to work with a specific framework, but you still want to isolate the inner workings of the Service from the MVCI framework.

Conclusion

I cannot stress how ridiculously simple it is to implement MVCI. Take these 15 lines of code:

class SkeletonModel {}

class SkeletonInteractor(private var model: SkeletonModel){}

class SkeletonViewBuilder(private var model: SkeletonModel): Builder<Region> {

override fun build(): Region {

TODO("Not yet implemented")

}

}

class SkeletonController() {

private val model = SkeletonModel()

private val interactor = SkeletonInteractor(model)

private val viewBuilder:Builder<Region> = SkeletonViewBuilder(model)

fun getView() = viewBuilder.build()

}

This took me 3 minutes and 12 seconds to type in from scratch (yes, I timed it). If you put it together with this:

class SkeletonApp : Application() {

override fun start(stage: Stage) {

stage.scene = Scene(SkeletonController().getView())

stage.show()

}

}

fun main() = Application.launch(SkeletonApp::class.java)

It will run. Okay, it will crash on the TODO in SkeletonViewBuilder.build(), but it will compile and run.

This is how I start every screen that I build. From here I usually start building the layout. As I add components to the layout, then I add the data elements to the Model as I go. In this way I have a working layout at all times. Sometimes I’ll just hard code starting values in the constructors of the fields in the Model, sometimes I’ll initialize them in the init{} block in the Interactor.

At the beginning, I’m interested in the Interactor as a tool to test my GUI, so the methods I create there are designed to simulate business logic that generates data sets that challenge my layout. Later, I can address actual business logic without worrying too much about how it impacts the GUI.

In this way, MVCI doesn’t just organize my projects, it actually becomes a tool that accelerates and simplifies development.

All this stuff is just second nature to me now, and even if I’m doing something trivial I’ll start with those same 15 lines of code. It’s just that useful.

Hopefully, you’ll find it useful too.