One of the biggest issues that JavaFX beginners (and a lot of non-beginners, too) face is how to create a busy GUI that does not get bogged down and laggy. Animations that should be smooth can stutter and pause, and the GUI can even become completely unresponsive from time to time. Things that should never happen to a UI.

How does this happen? This often gets blamed on the “Lengthy GUI Task”. The idea that the GUI gets caught up doing something long and complex and cannot service the other tasks and requests that are constantly coming in.

I believe this to be largely a myth. Most of the time when the FXAT is occupied performing a long task, most of that task has nothing to do with the GUI and should be executed on a background thread. That background thread should then submit the actual GUI updates to the FXAT, as they are required, using one of the standard JavaFX techniques.

Another StackOverflow Question

I see a lot of StackOverflow questions that get closed without an answer because they don’t fit the narrow range of criteria that StackOverflow mandates for question quality. Often this is because the questions are too broad and don’t lend themselves to a specific answer. A lot of times, however, these overly broad questions raise great issues which lend themselves to a longer discussion.

This recent question, brought up a topic which plagues a lot of developers, and doesn’t seem to be going away any time soon:

I’m frustrated in not being able to have multiple independently operating UI elements in FX. As a simple example, I can put a counter (textbox with an AnimationTimer that updates it counting as fast as it can), and it works fine just sitting there. But as soon as I start to do other things in the UI, it interrupts my counter causing it stall/pause momentarily.

How can I have a timer (let alone sophisticated animated charts or something) that continue to update seamlessly and independently of anything else going on in the UI?

In response to one of the comments, the OP elaborates a bit more:

What I’m asking for is a way to have multiple UI threads - so that something going on in UI thread A does not impact what is happening in UI Thread B. If that is simply not possible in FX, then it “is what it is”, but I wonder how one would write something like a stock trading App, where where there are multiple windows with continuously updating charts, graphs, etc. that are not paused when a lengthy UI task is going on in another window.

So there you have it in a nutshell. The OP is having difficulty with a GUI that’s suffering from performance issues and suggests (not unreasonably) that perhaps having more than one FXAT would solve the issue as the GUI could then multitask. The assumption is that this is necessary because of “lengthy UI tasks”.

What is a Long GUI Task?

I have come to believe that there is no such thing. The question seems to imply that updating charts and graphs would meet the definition. But what is “updating charts and graphs”? To me, that would mean that my code would update some kind of ObservableList, since those are the foundations for TableView, ListView and Charts. The code that runs on the FXAT shouldn’t do anything else.

But wouldn’t that trigger a lengthy GUI task inside the JavaFX library? That seems like a reasonable question to me. I strongly suspect, however, that the developers of the JavaFX library would have thought of that and avoided that problem. But it’s worth looking to see.

Simulating a Busy, Busy Screen

I’ve never written a stock trading application, but I think it’s clear what the question is asking about. Imagine a screen with a number of graphs and charts that are constantly being updated with data from external API’s. Possibly multiple sources, and many updates each second. It’s vital that the screen is constantly refreshed with the latest data so that the user can make split second decisions.

The implication here is that the sheer quantity of updates is somehow causing so much work for the FXAT that it can’t keep up with it with just a single thread, and that having the ability to have multiple threads would make the screen more fluid.

Now that’s something that we can simulate fairly easily:

public class LongUiTask extends Application {

public static void main(String[] args) {

launch(args);

}

private static int buttonNumber = 0;

@Override

public void start(Stage primaryStage) {

FlowPane pane = new FlowPane();

pane.getChildren().addAll(IntStream.range(0, 80).mapToObj(idx -> createButton()).collect(Collectors.toList()));

pane.getChildren().addAll(IntStream.range(0, 20).mapToObj(idx -> createTimerButton()).collect(Collectors.toList()));

primaryStage.setScene(new Scene(pane));

primaryStage.show();

}

@NotNull

private Button createTimerButton() {

Button timerButton = new Button("Timer");

timerButton.setOnAction(startEvt -> {

IntegerProperty counter = new SimpleIntegerProperty(0);

Timeline timeline = new Timeline(new KeyFrame(Duration.seconds(10000), new KeyValue(counter, 10000)));

timerButton.textProperty().bind(Bindings.createStringBinding(() -> Integer.toString(counter.get()), counter));

timeline.play();

});

return timerButton;

}

private Node createButton() {

Button button = new Button("Start - " + buttonNumber++);

button.setOnAction(evt -> countFast(button));

return button;

}

private void countFast(Button button) {

Thread thread = new Thread(() -> {

int counter = 0;

do {

try {

sleep(2);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

String theCount = Integer.toString(counter++);

Platform.runLater(() -> button.setText(theCount));

} while (true);

});

thread.setDaemon(true);

thread.start();

}

}

What This Application Does

This is a window with a single container in it; a FlowPane. Inside the FlowPane are 100 Buttons. The first 80 Buttons all launch background tasks that “count as fast as they can”, which is the situation that the StackOverflow question specifically posed. These background tasks are all written so that they update the label on their associated Button, converting the current count number to a String. Essentially, once each of these buttons are clicked, their labels will change to a rapidly incrementing counter.

The next 20 buttons each launch a JavaFX TimeLine, which will start a counter which will increment an IntegerProperty once each second. The IntegerProperty is then bound to the Text property of the Button so that it will display the current value of the IntegerProperty as a String. These “Timer” buttons are just that; timers which increment by one each second displaying how many seconds since they were clicked.

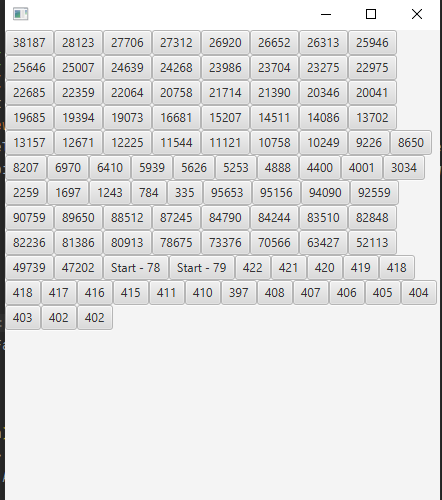

Up and running, it looks like this (with the numbers in the Buttons whizzing away like crazy):

What Does This Prove?

I chose FlowPane for the main container because it’s seems to be a fairly complicated layout for the GUI. All of the elements are arranged horizontally until the screen width is full, then it starts a new row below it and continues to place elements on that row until the screen width is full, and so on. When the buttons start to change their labels, their size changes and the layout has to be recalculated. Also, if you change the size of the Window, the layout will have to be re-evaluated as you drag the border in and out.

Is this as complicated as a dozen charts and graphs constantly updating? Maybe not, but JavaFX is really efficient at handling the display so it’s probably easy to overestimate the load that an updating chart actually puts on the FXAT.

The Timer Buttons are important because they are 100% FXAT, and they simulate how multiple simultaneous animations would run smoothly under a heavy load.

Is this a heavy load?

From a GUI perspective, I think it qualifies as a heavy load. Each of the background threads is generating just under 500 events on the FXAT each second, and there’s 80 of them, so that’s 40,000 events pushed into the queue each second. Not to mention 20 simultaneous animations happening on the Timer Buttons. (Note: I did some checking on the counters against real time, and it’s slower than 500 per second, so I’m assuming that there’s enough overhead in the sleep() itself that it puts in more than a 2 millisecond pause. So the number of events would be somewhat less than 40,000.)

Relating back to the original question, what if this was a stock trading application? Isn’t it possible that there could be 500 buttons with the current price of 500 different stocks? How would it handle that?

Assuming that you have some kind of normal access to stock market information, it’s highly unlikely that you are going to get API response times in the order of a few milliseconds for each request. Even if you could get 5 updates for each stock each second, that’s still only 2,500 updates to the GUI each second, less that 10% of the number of updates that this application posts to the FXAT.

And the Results?

For me, everything went smoothly until I clicked on the last couple of Start buttons. I already had all of the Timers running. Up to around Start button number 75 all of the counter numbers were spinning away faster than the eye could see and everything was fluid. When I had all of the Start Buttons clicked, the numbers started to update about once every second, so the GUI was definitely affected.

With a lot, but not all of the Buttons clicked, things moved smoothly until I moved the cursor around the window. Mouse moves generate a LOT of events on the FXAT - thousands of events in a short period of time, and I suspect that these were pushing the GUI into overload.

Another quirk about this is that you can click on a button a second time and it will launch another background thread which will start updating the button number. So the number will flicker back and forth between two counters as each thread’s events update it. I started up about 30 of the Buttons and waited until the first few had hit 100,000. Then I clicked the first one again. The result was that the Button was now alternating between a 6 digit number and a much shorter number, causing the Button to resize and the FlowPane to re-evaluate the layout. I had the window sized up so that 6 Buttons with 6 digit numbers would fit across a row, but 7 would fit if the first Button had less digits. The result was that the screen was largely unreadable, but because the layout was reworked causing the buttons to flicker around from place to place on the screen. This was exactly as you’d expect if everything was working properly.

When I first wrote this test application, there was no sleep() in the countFast() loop. I think this was pretty close to having an infinite NOP loop, and it caused grief with the whole JVM. Even my IDE started to hang. So it’s not totally clear whether having nearly 80 background threads is causing some resource issues within the JVM and is affecting the GUI, or whether it’s the sheer number of events generated by those threads.

I tried using a 1 millisecond sleep time, and it started to have trouble when about 45 counter Buttons had been clicked.

But What About Charts and Graphs?

I did some further testing. I created a screen with a LineChart and one of those counter Buttons from my test program above.

Then I loaded up 30 XYChart.Series into the LineChart, and launched a background task for each one that would create an (x,y) pair for each chart with x incrementing by one each time, and the y randomized a bit, but trending up. Each series started x =1 and y as a random number between 0 and 300. The background task looped around a 200 millisecond sleep, and then added a new (x,y) pair to its series. To keep the data series from becoming ridiculously huge, when x got to 1000, it reset it to 1 and any previous (x,y) with the same x was removed from the series. The logic looked like this:

Optional<XYChart.Data<Number, Number>> dataToRemove =

seriesData.stream().filter(data -> data.getXValue().equals(theCount)).findFirst();

Platform.runLater(() -> {

dataToRemove.ifPresent(seriesData::remove);

seriesData.add(new XYChart.Data<>(theCount, theValue));

});

How did this run?

Perfectly. The LineChart used animation to restructure itself as the data sets grew to 1000 points, and then as the y values trended upwards. There should have been about 5 data points added each second for each of the 30 data sets. The counter Button was running and the numbers whizzed by faster than I could follow. At no point did anything on the LineChart or the Button stutter or pause.

Yes, But Those GUI Tasks are Small

That’s the point.

The user code in the FXAT should be small if you are taking the correct approach. When I design a JavaFX application I try to have all of the layout done in the setup at the beginning. I create a model that holds the data as properties, and bind those properties to the screen elements when creating the layout. Then very little of the code that runs after the setup will touch any of the screen at all, it just updates the properties in the model. A couple of exceptions to this would be:

- Changes to the screen display to disable elements when a background task is running. For instance, if I want to disable a Button as soon as it’s clicked that could happen in the Event Handler for the

onAction()method of the Button. - If the application needs to open up a DialogBox or some other on-the-fly screen element.

Of course, these kinds of layout changes aren’t going to be happening 200 times a second either.

Keep the Back End in the Background

Look at the code snippet above for the XYChart.Data pruning. Do you see how the stream() functionality is run in the background thread? I assumed that streaming through 1000 items looking for a specific x value could be a little time intensive, so I put that part in the background and stored the result in the Optional. Then the actual update to the ObservableList, to remove that item, was done on the FXAT.

When I first wrote this test application, my countFast() method looked like this:

private void countFast(Button button) {

Thread thread = new Thread(() -> {

AtomicInteger counter = new AtomicInteger();

do {

try {

sleep(2);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

Platform.runLater(() -> button.setText(Integer.toString(counter.getAndIncrement())));

} while (true);

});

thread.setDaemon(true);

thread.start();

}

I used AtomicInteger as a container for the counter because with the Platform.runLater() parameter being a lambda expression, it needed to be “final or effectively final”. The problem is that the counter.getAndIncrement() call is happening on the FXAT. It’s a small thing here, but that background thread has one job only - increment the counter every 2 milliseconds - and it was passing it off to the FXAT!

This is extremely easy mistake to make, and most of the time when users have issues with performance in JavaFX it’s because this is what they’ve done. They’ve put back end work into the FXAT.

It’s tempting to use the background task for nothing but the sleep(), and then put everything in the Platform.runLater(), but don’t do it.

Summary

When I first started looking at this my thought was, “Who needs a counter that updates 500 times a second?” When I saw it running, though, I realized that the fluidity of the counter changing, and it’s perceived speed (mostly by watching the digits at the beginning of the number), can be valuable feedback to the user. I wasn’t expecting that.

It seems from what we’ve seen here that internal GUI updates and layout changes are optimized nicely by the JavaFX library. In that case, we don’t need to worry about those routines causing issues with the GUI response.

It is possible to overload the GUI by submitting massive numbers of jobs to the FXAT from background tasks. But it really takes a lot.

The key to success is to keep your GUI tasks as small as possible. Only do the things that need to be on the FXAT on the FXAT. Avoid running hundreds of lines of layout code in response to the results of a background process. Build the layout first, and then control its display through data bindings to your model.

And no, you don’t need a second FXAT to multi-task the GUI.