Wordle

This simple game is everywhere right now (the beginning of 2022) and it seems like everyone is playing it. As I was writing this article, it was announced that Wordle was sold to the New York Times, who will host it in the future.

If you don’t know about Wordle you should go and take a look at it here. The website has all of the information that you need to understand how the game works, and you can play it (once a day) to see how it looks when it’s running.

The game mechanics are very similar to “Mastermind”, where you get clues about which letters are correct, and which are letters in the word but not in the correct place. It’s different in these respects:

- The indicators are on the guessed letters themselves

- You know exactly which letters are correct

- You know exactly which letters are in the wrong place

- The guess has to be an actual word in the English language

- You only get six guesses

All of these differences make the game a little easier than “Mastermind”, but the requirement to use real words makes it feel tougher even though this factor limits the field of possible answers.

Finally, Wordle generates just one target word each day, for the entire world, and you only get to play it once per day.

WordleFX

WordleFX is written to be an absolute clone of Wordle in terms of look and game play. You get one word per day, and it’s the same word as on the website. It doesn’t lock you out if you’ve lost and restart it, or just restart it part-way through so you can start over. So it has no feature to share your results - that wouldn’t be fair.

WordleFX wasn’t really created to be replacement for playing Wordle on the Web. It’s intended to be a demonstration of how Reactive JavaFX can be used to create a highly interactive and interesting interface in an application. It’s also intended to be a demonstration of how CSS styling can be used as an integral part of a user interface.

The Code

This article doesn’t contain a lot of code samples. The entire application is about 350 lines of code in 10 classes. Seven of those classes have less than 40 lines of code. No class is more than 80 lines long, so it should be fairly easy to wrap your mind around how the application works.

WordleFX is written in Kotlin because … Kotlin. There’s nothing too crazy in here, and if you understand Java should should be able to scratch your head a little bit and figure out what most of the code is doing. Maybe you’ll decide that Kotlin looks really cool and you’ll want to learn it - that would be awesome.

Probably the strangest thing to Java programmers will be “Scope Functions”, especially apply which is used copiously in WordleFX to configure Nodes. You can find out more about apply here.

And no, you don’t need TornadoFX to write JavaFX applications in Kotlin.

So go take a look at the source code in GitHub if you’re interested:

Appearance of the Application

As part of this exercise, both light mode and dark mode have been implemented entirely in the CSS. CSS styling is crucial to this application, and most of the user feedback is achieved by manipulating pseudo classes in the style sheets.

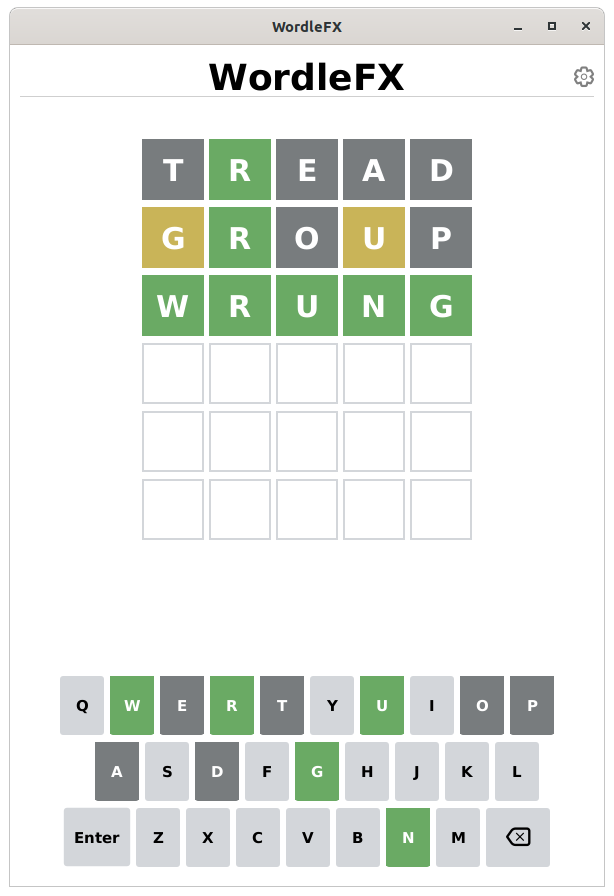

The application looks like this:

Animations

One of the biggest challenges in writing this application is to handle the animations, which really give the game its feel.

There are four animations:

- When a letter is selected, the tile “flashes” briefly.

- When the guess results are revealed, the tiles flip over to show their colour.

- When an invalid word is entered and checked, the entire row of tiles wiggle briefly.

- When an invalid word is entered and checked, a toast with an error message fades in, displays briefly and then fades out.

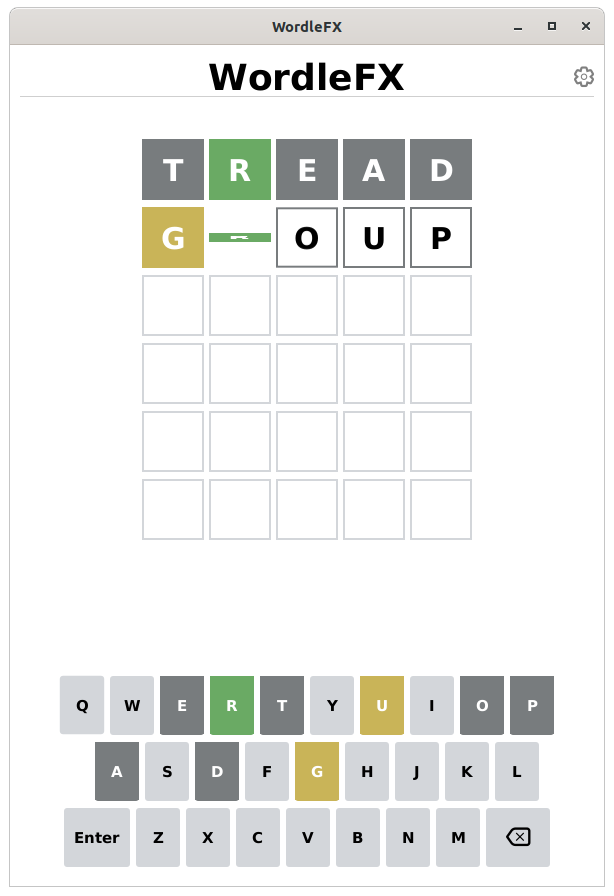

Here’s what the tiles look like in motion:

Design Notes

Reactive Design

The design of WordleFX is 100% Reactive. There is a Model, which is the application “State”, and all of the components interact with each other indirectly by manipulating or responding to changes in the elements of “State”.

Including Animations and Pseudo-Class Changes

Animations are necessarily imperative in nature. They are actions that are triggered and happen at a particular moment in time. This can be particularly challenging when animations are involved with changes in the GUI presentation of some element, as those changes cannot simply be bound to the Model since they need to co-ordinate with an animation.

At the same time, most of the GUI presentation changes are achieved through Pseudo-Class changes, which are also not Reactive in nature and require Listeners in order to work. It’s possible to include the Pseudo-Class change on the Node in the animation, or to co-ordinate it with the invocation of the animation.

Model-View-Controller-Interactor

WordleFX is built with an MVCI structure, which is MVC with an added component, the “Interactor”. All of the game play logic is contained within the Interactor, which responds to events from the GUI and updates the Model. The View is composed of two major components; the game field containing the letter tiles, and the virtual keyboard.

This is all tied together by the Controller which instantiates everything and supplies Runnables and Consumers to the virtual keyboard to invoke methods in the Interactor. It also installs a Keyboard event handler on the entire View so that the user can use either the virtual keyboard or a real keyboard.

Low Coupling

One of the key goals of any good application design is to reduce coupling as much as possible. In WordleFX, you’ll only find the following coupling:

- Layout Coupling

- Any layout is comprised of container classes (parents) which hold other Nodes (children) inside them. This kind of coupling is unavoidable, but its impact is reduced by ensuring that parents have as little knowledge of the nature of their children as possible. Virtually all child objects are returned from their builder functions as instances of Node or Region.

- Coupling To the Model

- The goal of MVC is have - as much as possible - the coupling happen exclusively with the Model and only the Model.

- Public Interactor Methods

- Every public method in a class adds to coupling but for the Interactor this is unavoidable, as the Controller needs to be able to call specific functions. Additionally, in pure MVC the Interactor functions would be inside the Controller. The MVCI structure physically isolates the business logic into the Interactor, which is an improvement in clarity, but then it needs to be exposed to the Controller in order to work.

Other than the parent->child relationships, every element of the GUI in WordleFX is completely independent and has no relationship, or knowledge of, any other element of the GUI.

An Example of How this Works

In WordleFX, the controller instantiates the Virtual Keyboard, supplying it Runnables and Consumers which will invoke methods in the Interactor in its constructor. The Virtual Keyboard needs these functional elements to handle the individual letter clicks, to handle the backspace key, and to process the guess when the <Enter> button is clicked. The only other dependency that the Virtual Keyboard needs is a map of LetterStatus keyed on each letter of the alphabet.

What each of these functional elements does is not known to the Virtual Keyboard. It’s job is simply to invoke the appropriate Consumer or Runnable when each button is clicked. At the same time, the Controller has no knowledge of how the Virtual Keyboard will implement these functional elements.

Then the Controller passes the Virtual Keyboard to the ViewBuilder in its constructor. The ViewBuilder accepts it as an instance of Region, and has no knowledge of its function or its true nature. As a Region it simply inserts it into it’s layout as a child.

Finally, the ViewBuilder passes the View back as a Region. The Controller then installs a KeyEvent Listener on it, to handle the keystrokes from the physical keyboard. The View has no role in this other than to be a target for the Events which, in turn, have no need to know anything about the View.

From this you can see that the main part of the View has absolutely nothing to do directly with any user input. All of the “Action” type of interactions are set up by the Controller.

As a matter of fact, you could remove the KeyEvent listener, and the application would run just fine - albeit without any physical keyboard input. Conversely, you could replace the Virtual Keyboard with an empty Pane, and the application would still work with physical keyboard input - however in this case you’d lose the clues in the colours of the Virtual Keyboard buttons.

Implementation Notes

Tile Status

There are 5 possible states that a tile can be in:

- Empty

- The tile has nothing in it.

- Unchecked

- A letter has been placed in the tile, but it has not been checked against the solution word

- Wrong

- A letter has been placed in the tile, it has been checked and that letter does not appear in the solution word

- Present

- A letter has been placed in the tile, it has been checked and found to be present in the word, but not in that position

- Correct

- A letter has been placed in the tile, it has been checked and found to match the letter in that place in the solution word

These statuses have been created in an Enum called LetterStatus. Since the determination of Pseudo-Class colours is virtually 100% controlled by the value of a Node’s related LetterStatus, the code for updating PseudoClass based on LetterStatus has been included in the LetterStatus class.

Does this break some design rules, having GUI elements tied to an element in the Model? I’m not sure, but it avoids “feature envy” by having some other class performing logic based solely on the contents of LetterStatus.

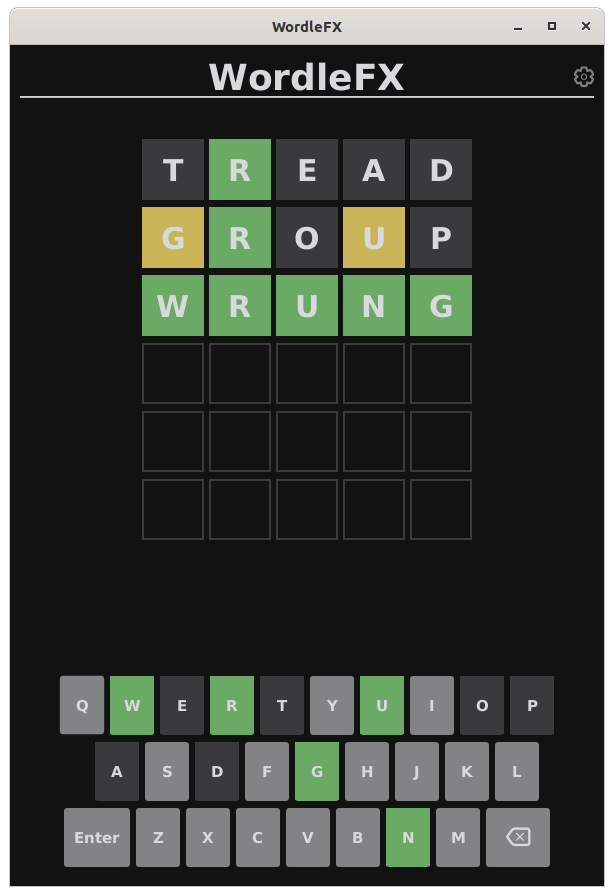

Dark Mode

WordleFX supports the Wordle Dark mode, as well as the Light mode. Mostly this is just to demonstrate how sweeping changes to the look of the application can be made by organizing the CSS properly and using Pseudo Classes.

Dark mode looks like this:

All of the colours in the CSS are defined and named in the .root section of the CSS. The pseudo-class for “dark-mode” modifies those definitions:

.root{

-white-colour: white;

-wrong-colour: #787c7e;

-text-fill-colour: black;

-empty-border-colour: #d3d6da;

-unlocked-border-colour: #787c7e;

-background-colour: white;

-key-background-colour: #d3d6da;

-toast-background-colour: black;

-toast-letter-colour: -white-colour;

-present-colour: #c9b458;

-correct-colour: #6aaa64;

}

.main-screen: dark-mode {

-white-colour: #d7dadc;

-wrong-colour: #3a3a3c;

-text-fill-colour: -white-colour;

-empty-border-colour: #3a3a3c;

-unlocked-border-colour: #565758;

-background-colour: #121213;

-key-background-colour: #818384;

-toast-background-colour: -white-colour;

-toast-letter-colour: black;

}

The “main-screen” selector is applied to the VBox which contains the entirety of the window, and when the pseudo-class is applied to it the definitions of these colours will change for all of its child Nodes, thereby enabling Dark mode.

The trigger for the mode change is the “Gear” icon in the top right corner of the screen.

Ikonli FontAwesome

WordleFX uses the Ikonli library for integrating FontAwesome into JavaFX to handle icons. This library provides a class FontIcon which you can use just like Text in an application. In WordleFX, the “gear” icon in the top right corner of the screen, and the “backspace” icon on the Virtual Keyboard are FontIcon.

Animations

All of the animation code is contained in a separate file of package level functions called “WordleAnimations.kt”. All of these functions simply accept a Node as a parameter, and would work equally on any kind of Node passed to them.

All of these animations require multiple steps to complete, and most of them use SequentialTransition to chain several Transitions one after the other.

Flipping Tiles

In Wordle, the tiles flip one after the other, possibly with each tile starting to flip before the previous tile has finished (this is how it’s implemented in WordleFX).

How do we keep each tile independent but still have the tiles flip sequentially?

The answer is, they aren’t really flipping sequentially! Each one has a delay, courtesy of PauseTransition which is run at the beginning of the sequence. The length of the delay is based on the Column property of the LetterModel which is installed on the tile. So all of the flip sequences are running virtually in parallel, but the first step in each one is a pause which varies from 0 to 2000 milliseconds.

Here’s the code:

fun flipTile(node: Node, column: Int, letterStatus: LetterStatus) {

SequentialTransition(PauseTransition(Duration(column * delay)), RotateTransition(Duration.millis(speed), node).apply {

byAngle = 90.0

axis = Rotate.X_AXIS

setOnFinished { LetterStatus.updatePseudoClass(node, letterStatus) }

}, RotateTransition(Duration.millis(speed), node).apply {

byAngle = -90.0

axis = Rotate.X_AXIS

}).play()

}

The other thing to notice about this is that the call to update the PseudoClass happens in the EventHandler at the end of the first RotateTransition. So, in Light mode, the tile is white until it rotates 90 degrees down when it’s essentially edge on and invisible, the colour changes, and it rotates back up again. The colour change makes it look like it’s doing a single 180 degree rotation.

Wiggling Invalid Words

The animation itself is fairly straight-forward. Move the Node 5 pixels to the left, run repeated TranslateTransition to move it 10 pixels to the right and back, and then put it back where it started at the end of the TranslateTransition:

fun wiggleRow(node: Node) {

node.translateX = -5.0

TranslateTransition(Duration.millis(50.0), node).apply {

byX = 10.0

cycleCount = 6

isAutoReverse = true

setOnFinished { node.translateX = 0.0 }

play()

}

}

The big question about this was how to trigger it in a Reactive manner. All of the tiles are independent, but the wiggle needs to happen based on the entire row, and triggered when the Interactor decides the word is invalid.

In truth, the animation doesn’t care if the tiles are wiggled together or in a group. The effect would be the same if 5 transitions (one per tile) were triggered in a millisecond of each other, or if the whole row is wiggled as one Node.

The real challenge was to implement it in State, so that it would work.

Originally, the tiles were implemented on the screen in a GridPane. That would have meant adding a new component to the LetterModel to make each tile aware of what row it was on (column was added to LetterModel to facilitate the flip delay). However, since the tiles were all identical in shape, there really wasn’t any need to have them in a GridPane, and it was just as effective to put them in HBoxes, all contained in a VBox. This meant that there was now a screen Node that corresponded to a single guessed word.

Now, how to trigger the wiggle?

First Implementation

Since you can only have one active guess at a time, and you can move on to the next while the current word is invalid, I decided to implement an IntegerProperty in the Model called InvalidRow. Originally, it would be set to 99, which wouldn’t correspond to any row on the screen. Then it would be changed to the current row if the word was found to be invalid.

The HBox for the word row looked like this:

private fun createRow(row: Int) = HBox(5.0).apply {

alignment = Pos.CENTER

children += IntRange(0, 4).map {

letterBox(model.letters[row][it])

}

model.invalidRowProperty().addListener { _ ->

if (model.invalidRow == row) {

wiggleRow(this)

}

}

}

This felt really kludgey. But on the other hand, it seemed very direct and simple to understand.

There was one problem, however…

What if the word was invalid the second time that it was checked?

In this case, the InvalidRow property would already be set to the current row, and the InvalidationListener wouldn’t be triggered. It was possible to get around it though.

Here’s the code from the Interactor that handled word validity:

if (data.isWordValid(guess.map(LetterModel::letter))) {

.

.

.

} else {

model.invalidRow = 99

model.invalidRow = model.currentRow

}

This worked, but really set off alarm bells. Essentially what this code does is treat a State element like a trigger, instead of a representation of “state”. The invalid row didn’t actually change. Also, there’s no guarantee that JavaFX isn’t going to detect that value wasn’t really changing, and not trigger the invalidation.

A Small Improvement

It made a little more sense like this:

model.invalidRow = 99

if (data.isWordValid(guess.map(LetterModel::letter))) {

.

.

.

} else {

model.invalidRow = model.currentRow

}

And you could argue that before the word is actually checked it’s not invalid and the change to State reflects this.

But it still seemed round-about and kludgey.

The Final Version

A more direct way makes sense, even though it complicates the Model a little bit. The Model was changed to remove invalidRow and replace it with this:

val wordValidity = List(6) { _ -> SimpleBooleanProperty(true) }

val wordsValid: BooleanBinding = run {

var results = SimpleBooleanProperty(true).and(wordValidity[0])

wordValidity.forEach { results = results.and(it) }

results

}

The BooleanBinding that does an and on each of the elements of wordValidity is needed because the toast display of the error message when an invalid word is checked needs to know if any of the words is invalid. It will now listen to wordsValid.

The word checking part of the Interactor isn’t really that different, it now just updates the wordValidity element that corresponds to the row being checked:

model.wordValidity[model.currentRow].set(true)

val guess = model.letters[model.currentRow]

if (data.isWordValid(guess.map(LetterModel::letter))) {

performCheck(guess)

model.currentRow++

model.currentColumn = 0

setAlphabet()

} else {

model.wordValidity[model.currentRow].set(false)

}

In the Model, this feels like more work, but in terms of the Interactor and the View, it’s now much more direct and easy to understand.

Checking Words

Wordle has two lists, one is a list of candidate words from which today’s word will be selected. The second is a list of every five letter word in the English language that isn’t a candidate word. Presumably the candidate words were cherry picked to be more common and therefore fair to the average player. It’s hard to imagine anyone actually guessing a word like “zanze”. However, any word from either list is considered a “valid” word, and can be entered as a guess.

The JavaScript for Wordle simply has both lists hard-coded into the source code. WordleFX has them split out into text files in the project resources. They’re read when the application is started, and stored as lists.

The code for determining the result for each letter in each guess is the most complicated part of the application. This is because if a guess contains repetitions of a letter which appears in the solution fewer times than in the guess, it only gets one “Correct” or “Present” result for each time the letter appears in the solution.

For instance, if the solution is “SCRAM” and the user enters “MUMMS” as a guess. Then only the first “M” should get a “Present” result, and the second and third should get “Wrong”. If the solution is “GUMMY” for the same guess, then the second and third “M” should get “Correct”, and the first should get “Wrong”.

Let’s look at the code for checking a word:

private fun performCheck(guess: List<LetterModel>) {

val presentLetters = model.word.filterIndexed { index, c -> guess[index].letter != c } as MutableList<Char>

model.wordGuessed = (presentLetters.size == 0)

guess.forEachIndexed { column, letterModel ->

val letter = letterModel.letter

letterModel.status = LetterStatus.WRONG

if (model.word[column] == letter) {

letterModel.status = LetterStatus.CORRECT

} else if (presentLetters.contains(letter)) {

letterModel.status = LetterStatus.PRESENT

presentLetters.remove(letter)

}

}

}

The MutableList, presentLetters is created by filtering out every letter in the solution that has been guessed correctly. This leaves only letters which are candidates for the “Present” result. If presentLetters is empty, then it means that every letter in the solution has been guessed correctly and the game is over.

Now, for each letter in the guess, we check to see if it’s a match against the corresponding letter in the solution and give it a “Correct” status if it is. If it’s not, then we only need to check to see if it’s in the presentLetters list. If it is, then we mark it as “Present” and the delete that letter from presentLetters. This way, we can only get one “Present” status for each occurance of a letter in the solution.