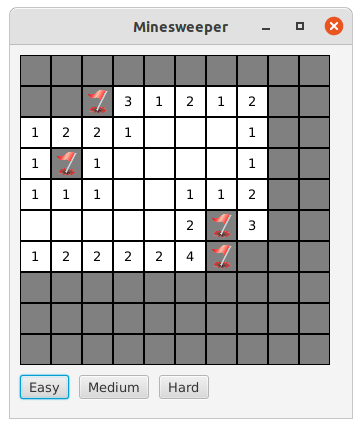

Model - View - Controller is a design pattern that has become the defacto standard for building web sites and business applications worldwide. It can be used effectively with JavaFX, but how to do so properly is not very well understood or very well documented. MineSweeper is a simple game that can be used to illustrate how to implement MVC in JavaFX, and also to show how a lot of functionality can be packed into very simple code with JavaFX.

The structure of this application uses the Reactive nature of JavaFX in virtually all of its design aspects.

Recently, I saw a question on StackOverflow from someone attempting to build a MineSweeper game in JavaFX. The question itself doesn’t matter - and it was later deleted by the person asking the question - but the sample code that was posted was extremely complicated and did not work very well.

I wondered just how simple a MineSweeper program could be if it was written with a strict MVC approach. The nice thing about using MineSweeper as an example is that it has no outside API to interact with and no persistence layer, so that everything can be done on the FXAT. This way, we can concentrate on the MVC structure and how to implement it without have to complicate things with background processing and threading issues.

MineSweeper - The Rules

Everybody probably already knows MineSweeper - it’s a game with a grid of grey squares, and when you click on a square it turns white to reveal:

- Nothing - No mines are in any adjacent squares

- A Number - How many adjacent squares have mines in them

- A Mine - Boom! You lose

The goal is to click on all of the squares that don’t contain a mine, leaving only the squares with mines in them unclicked.

Another important idea about the game-play is that it shouldn’t ever be left to chance alone at the beginning. So the first square you click cannot be a mine. Nor can it have any adjacent mines, as you wouldn’t yet have enough information to make a non-random choice about which square to click second. The main impact this has on designing the game is that the contents of the squares cannot be determined until the user clicks on the first square.

A Quick Review of Model-View-Controller

Model-View-Controller is a design pattern that divides a system - or a component of a system - into three parts:

- The Model This holds the data which is used by the View. In JavaFX, the model is composed of Observable objects and lists.

- The View The View is strictly the component which handles the display and user interaction elements of system. It has no business logic, and binds screen components to the Observable objects in the model.

- The Controller The Controller is responsible for instantiating the Model and the View, and communicating with the rest of the system. It is the only MVC component which has methods visible outside of the MVC structure. The Controller also contains all of the application logic.

The idea is that the screen components and UI are a black box and could, theoretically at least, be swapped out for any number of designs without modifying the Controller or the Model. At the same time, the View does not contain any application logic, it’s strictly a user interface that delegates any application decisions back to the Controller.

The Components

This implementation of the game is built with two MVC constructs, the game board and the cells. A great deal of care is taken to ensure that all of the functionality is placed in the element where it belongs. This means that the Cell MVC is responsible for everything that goes on inside a cell, and the game board MVC is responsible for the game board activities and anything that involves multiple cells.

This design is especially interesting because it illustrates how a more complicated application with many layered and interdependent components could be constructed. Think of each MVC as a component, with the entirety of its API exposed through the Controller.

The Cell

The Cell is an autonomous, self-contained unit. Other than having a public method which will tell whether or not an (x,y) cell co-ordinate is one of its neighbours it isn’t particularly aware of existing in the context of a grid. It doesn’t have any functionality which is dependant on any other Cells, or the Game Board itself.

The CellModel

The CellModel is fairly simple, mostly a collection of boolean properties:

class CellModel {

private final BooleanProperty clicked = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

private final BooleanProperty isMine = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

private final BooleanProperty isFlag = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

private final StringProperty mineCount = new SimpleStringProperty("");

public BooleanProperty clickedProperty() {

return clicked;

}

public BooleanProperty isMineProperty() {

return isMine;

}

public BooleanProperty isFlagProperty() {

return isFlag;

}

public StringProperty mineCountProperty() {

return mineCount;

}

}

We need to know if the Cell contains a mine, if it’s been clicked, what number to display when it’s clicked (assuming it’s not a mine), and whether we should show the flag to indicate that it’s been right clicked. That’s all.

I chose not to use delegate getters or setters for these properties because it wouldn’t add any extra control or make anything easier to understand given how simple the Controller is.

The CellView

The CellView needs to display some of 4 possible things:

- A gray or white rectangle as a background.

- And one of the following:

- A Flag

- A Mine

- A Number

The best layout for the Cell is a StackPane, with the everything loaded up in it at the beginning, and the visibility of the components bound to the properties in the CellModel. The Rectangle needs to go at the bottom, but the other three components can go in any order as only one of them will be visible at a time:

class CellView extends StackPane {

private static final Image mineImage = new Image("/images/MineSmall.png");

private static final Image flagImage = new Image("/images/Flag.png");

CellView(CellModel model, Consumer<MouseButton> clickConsumer) {

Text mineCountText = new Text("");

ImageView mineImageView = new ImageView(mineImage);

ImageView flagImageView = new ImageView(flagImage);

flagImageView.setFitHeight(24);

flagImageView.setFitWidth(24);

getChildren().addAll(createRectangle(model.clickedProperty()), mineCountText, mineImageView, flagImageView);

mineCountText.textProperty().bind(model.mineCountProperty());

mineCountText.visibleProperty().bind(model.clickedProperty().and(model.isMineProperty().not()));

mineImageView.visibleProperty().bind(model.clickedProperty().and(model.isMineProperty()));

flagImageView.visibleProperty().bind(model.isFlagProperty().and(model.clickedProperty().not()));

setOnMouseClicked(evt -> clickConsumer.accept(evt.getButton()));

}

private Rectangle createRectangle(ObservableBooleanValue clickedProperty) {

Rectangle rectangle = new Rectangle(30, 30);

rectangle.fillProperty()

.bind(Bindings.createObjectBinding(() -> clickedProperty.get() ? Color.WHITE : Color.GRAY, clickedProperty));

rectangle.setStroke(Color.BLACK);

return rectangle;

}

}

The mine and the flag are just images. I wasn’t able to quickly find a small enough flag image, so I scaled it in the code when it was loaded into its ImageView. StackPane's centre everything in them by default, so there’s no need to fuss about with alignment either.

The Rectangle starts out gray, and then flips to white when the cell has been clicked, so the binding for that converts the boolean property into a Color via the Bindings library createObjectBinding(). For the other bindings, I’ve just used the Fluent Binding API since they are direct bindings of the model properties joined with and() and possibly modified with not().

The Cell Controller

The Controller for each Cell is just the Cell object itself. It instantiates the CellModel as a field, and then passes it to the constructor of the CellView:

public class Cell {

private static final Random RANDOM = new Random();

private final int x;

private final int y;

private final CellModel model = new CellModel();

private final Region cellView;

public Cell(int x, int y, BiConsumer<Integer, Integer> clickConsumer) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

Consumer<MouseButton> viewClickConsumer = mouseButton -> {

if (mouseButton.equals(MouseButton.SECONDARY)) {

model.isFlagProperty().set(!model.isFlagProperty().get());

} else {

model.clickedProperty().set(true);

clickConsumer.accept(x, y);

}

};

cellView = new CellView(model, viewClickConsumer);

}

public Region getView() {

return cellView;

}

public void setNum(long num) {

model.mineCountProperty().set(num > 0 ? Long.toString(num) : "");

}

public int getX() {

return x;

}

public int getY() {

return y;

}

public boolean isMine() {

return model.isMineProperty().get();

}

public boolean notMine() {

return !isMine();

}

public boolean isNeighbour(int testX, int testY) {

if ((Math.abs(getX() - testX) <= 1) && (Math.abs(getY() - testY) <= 1)) {

return !((getX() == testX) && (getY() == testY));

}

return false;

}

public BooleanProperty clickedProperty() {

return model.clickedProperty();

}

public void setMineRandomly() {

model.isMineProperty().set(RANDOM.nextInt(10) <= 1);

}

}

One thing you’ll notice right away is the the “x” and “y” location of the cell aren’t part of the model! That’s because they have nothing to do with the CellView at all and they act more like domain objects in a business application. So they don’t belong in the View Model for the Cell.

The other thing to notice is the viewClickConsumer which is passed to the CellView. It would seem to be easier to just directly attach an EventHandler to the CellView with view.setOnMouseClicked(), so why not do that? This would violate the idea that the View is a black box by assuming that the design of the CellView makes it clickable itself. While the MineSweeper game generally assumes that mouse clicks are going to be the user interaction, it’s not cast in stone, and the implementation doesn’t have to make the whole CellView clickable. It’s possible it could be implemented with a pair of ToggleButtons, one for “flag” and one for “reveal”. We break that dependency by creating a Consumer, and passing it to the CellView via its constructor.

The viewClickConsumer still assumes that MouseButton is going to be sent back, but any implementation of CellView that doesn’t use mouse clicks can still convert its functionality to pass either MouseButton.PRIMARY or MouseButton.SECONDARY. This is maybe a bit of a kludge, and if I was making a large business application I’d probably create an Enum called CellAction and pass that back instead.

There’s surprisingly little logic inside the Cell. It really has only the following functions that aren’t getters or setters:

- It defines a click consumer that handles both left and right clicks.

- It can determine if any given x,y combination is one of its neighbours.

- It can use a random function to set it’s isMine Property

The notMine() method was added so that it could be access as a Method Reference in a Stream in the game Controller. It just makes that code look a little cleaner.

The MineSweeper Game Board

This is essentially the entire window for the game. There are three buttons to start (or restart) a game of various board sizes, the board itself, and some graphics to indicate win or lose.

The Model

The View Model for the game board is very simple, just 2 boolean properties:

private final BooleanProperty loseProperty = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

private final BooleanProperty winProperty = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

Rather than create a separate Model class for this, these have been left as fields in the Controller. This was really just to make a point; they still comprise the Model but they don’t *have * to be put into a separate class if it doesn’t make sense. In this case, they can be passed to the View in its constructor without resulting in a ridiculously long parameter list.

The View

The main screen View is a VBox with two compound elements. The first is a StackPane which contains the main GridPane at the bottom and two other StackPanes, each containing an image for win or lose on top of it. These two StackPane’s are only partially opaque, and have a different background colour.

The second part of the VBox is an HBox with a set of Buttons which start new games at different board sizes. The entirety of the action of these buttons is handled by the View Controller via the Consumer passed to the View in its constructor.

class MineSweeperView extends VBox {

private GridPane grid = new GridPane();

private Consumer<Integer> boardInitializer;

MineSweeperView(Consumer<Integer> boardInitializer, ObservableBooleanValue gameLostProperty, ObservableBooleanValue gameWonProperty) {

this.boardInitializer = boardInitializer;

initialize(gameLostProperty, gameWonProperty);

}

private void initialize(ObservableBooleanValue mineClickedProperty, ObservableBooleanValue unclickEmptyProperty) {

setSpacing(10);

getChildren().addAll(setUpMainGrid(mineClickedProperty, unclickEmptyProperty), setUpButtonBox());

setPadding(new Insets(10));

}

private Region setUpButtonBox() {

return new HBox(10, createTypeButton("Easy", 10), createTypeButton("Medium", 16), createTypeButton("Hard", 25));

}

private Region setUpMainGrid(ObservableBooleanValue gameLostProperty, ObservableBooleanValue gameWonProperty) {

return new StackPane(grid,

setUpWinLosePane(new ImageView(new Image("/images/MineBig.png")), Color.PINK, gameLostProperty),

setUpWinLosePane(new ImageView(new Image("/images/Win.png")), Color.BLUEVIOLET, gameWonProperty));

}

void addCell(int x, int y, Region cell) {

grid.add(cell, x, y);

}

void clearView() {

grid.getChildren().clear();

}

private Pane setUpWinLosePane(ImageView imageView, Color colour, ObservableBooleanValue revealProperty) {

Pane pane = new StackPane();

pane.setBackground(new Background(new BackgroundFill(colour, CornerRadii.EMPTY, Insets.EMPTY)));

pane.setOpacity(0.6);

pane.getChildren().add(imageView);

pane.visibleProperty().bind(revealProperty);

return pane;

}

private Node createTypeButton(String label, int newBoardSize) {

Button button = new Button(label);

button.setOnAction(evt -> boardInitializer.accept(newBoardSize));

return button;

}

}

Virtually all of the code in this View is involved with setting up the layout. There are only two methods not related to this; one which clears the GridPane of all of its children, and one which adds a Node to the GridPane at specified row and column. These are also the only two non-private methods in the View, aside from the constructor. It is possible to avoid having these two public methods by expanding the Model to have enough information to populate or clear the GridPane, but it wouldn’t result in a cleaner design.

The Game Controller

The Game Controller has the code which launches everything, and the code which needs to look at more than one cell at a time, which as it turns out, isn’t much:

class MineSweeperController {

private final BooleanProperty loseProperty = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

private final BooleanProperty winProperty = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

private final MineSweeperView view;

private boolean initialized = false;

private ArrayList<Cell> cells = new ArrayList<>();

private final BiConsumer<Integer, Integer> screenSizeHandler;

MineSweeperController(BiConsumer<Integer, Integer> screenSizeHandler) {

this.screenSizeHandler = screenSizeHandler;

view = new MineSweeperView(this::setBoardSize, loseProperty, winProperty);

}

private void setBoardSize(int newBoardSize) {

screenSizeHandler.accept((newBoardSize * 31) + 100, (newBoardSize * 31) + 32);

reset();

loadBoard(newBoardSize);

}

public Region getView() {

return view;

}

public void reset() {

winProperty.unbind();

winProperty.set(false);

loseProperty.unbind();

loseProperty.set(false);

cells.clear();

initialized = false;

}

public void loadBoard(int boardSize) {

view.clearView();

for (int i = 0; i < boardSize; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < boardSize; j++) {

Cell cell = new Cell(i, j, this::consumeBoardClick);

view.addCell(i, j, cell.getView());

cells.add(cell);

}

}

}

private void consumeBoardClick(int x, int y) {

if (!initialized) {

initializeBoard(x, y);

initialized = true;

}

System.out.println("***** (" + x + ", " + y + ")");

cells.stream()

.filter(Cell::notMine)

.filter(cell -> !cell.clickedProperty().get())

.forEach(cell -> System.out.println("\t" + "(" + cell.getX() + ", " + cell.getY() + ")"));

}

public void initializeBoard(int pressedI, int pressedJ) {

setMines(pressedI, pressedJ);

cells.forEach(cell -> cell.setNum(getNeighbors(cell.getX(), cell.getY()).stream().filter(Cell::isMine).count()));

winProperty.bind(createWinLoseBinding(Cell::notMine, Boolean::logicalAnd));

loseProperty.bind(createWinLoseBinding(Cell::isMine, Boolean::logicalOr));

}

private BooleanBinding createWinLoseBinding(Predicate<Cell> predicate, BinaryOperator<Boolean> reductionOperator) {

List<BooleanProperty> clickProperties = cells.stream().filter(predicate).map(Cell::clickedProperty).collect(Collectors.toList());

return Bindings.createBooleanBinding(() -> clickProperties.stream()

.map(BooleanProperty::get)

.reduce(clickProperties.get(0).get(), reductionOperator),

clickProperties.toArray(new BooleanProperty[0]));

}

private void setMines(int pressedI, int pressedJ) {

cells.stream()

.filter(cell -> !cell.isNeighbour(pressedI, pressedJ))

.filter(cell -> !((cell.getX() == pressedI) && (cell.getY() == pressedJ)))

.forEach(Cell::setMineRandomly);

}

public List<Cell> getNeighbors(int x, int y) {

return cells.stream().filter(cell -> cell.isNeighbour(x, y)).collect(Collectors.toList());

}

}

Setting Up the Board

This is really simple, just use two nested loops for the (x,y) coordinates of the board, instantiate a Cell for each iteration and pass it to the View to do something with it. What’s really interesting is that you don’t need a logical grid structure to store the Cell elements for doing any later processing. A simple List<Cell> will do. Since each Cell knows its own (x,y) coordinates, it can supply a method which will tell if any given (x,y) coordinate is one of its neighbours.

The original sample code in the StackOverflow question had a matrix: Cell[][] board that held all of cells in a grid. Then the board was traversed with two nested loops any time all of the cells needed to be checked. Replacing this with a List means that the nested loops can be simplified to simple Stream operations.

The First Click

The biggest complication in the game is that the first cell clicked has to be empty white. This means that none of the cell contents can be determined until that first cell has been clicked. For this reason, the game board controller passes a BiConsumer to the Cell constructors to handle the (x,y) location of the click. That BiConsumer calls consumeBoardClick() which will do nothing if it isn’t the first click.

Initializing the board is by necessity a two-pass operation. Pass 1 visits each cell, and if it isn’t the first cell clicked or one of its neighbours, then tell it to randomly set its isMine property. Pass 2 visits each cell, gets all of its neighbours and Streams them, filtering for the ones with isMine set to true. Then it counts them up and sets the cell’s number based on that.

The Win and Lose Properties

The last step in initializing the board is to bind the two win/lose properties to the cells. Let’s have a look a the conditions for “win” and “lose”

- Win

The player wins when **all ** of the cells with the

isMineproperty set to false have been clicked. - Lose

The player loses when any of the cells with the

isMineproperty set to true have been clicked.

Determining win or lose at any given time is simple; Stream a list of cells and check to see if any or all of them have been clicked. So we need two lists of cells, one with isMine set to true, and the other with false. However, we’re not really interested in the cells, just the isMine property contained in each one. We can use a map() function to transform the Stream of Cell into a Stream of BooleanProperty, and then collect them into a list.

We’re going to use the Bindings library to create this binding:

public static BooleanBinding createBooleanBinding(Callable<Boolean> func,

Observable... dependencies)

That’s straight from the JavaDocs for Bindings. The first parameter is just a Supplier, which is a functional interface that doesn’t take any parameters but returns a value of the type specified - in this case a Boolean. We just need to write a supplier that determine if the player has won or lost at the time that it is called. It’s important to note that this Supplier isn’t necessarily involved with properties and observables, it’s just ordinary Java that calculates a boolean value somehow.

The second parameter is an array of Observable objects that will trigger a recalculation of the Boolean whenever any one of them changes. For these cases, we’ll have a List of BooleanProperty that we can convert into an array.

Let’s see how this works:

private BooleanBinding createWinLoseBinding(Predicate<Cell> predicate, BinaryOperator<Boolean> reductionOperator) {

List<BooleanProperty> clickProperties = cells.stream().filter(predicate).map(Cell::clickedProperty).collect(Collectors.toList());

return Bindings.createBooleanBinding(() -> clickProperties.stream()

.map(BooleanProperty::get)

.reduce(clickProperties.get(0).get(), reductionOperator),

clickProperties.toArray(new BooleanProperty[0]));

}

The first step is to create a List<BooleanProperty> by streaming the entire list of cells, filtering them based on isMine() or notMine() and then extracting the clickedProperty() in a map function.

To determine the win/lose condition, the list of BooleanProperty will be Streamed, then the current value will be determined by calling the get() method of the property, and the Stream will be reduced to a single Boolean value by applying a Boolean operator between all of the elements. For this, “Any” means that we need to use OR as the operator, and “All” means that we need to use AND.

Even if you have trouble following exactly how it works, the calls to this method are pretty clear in their intent:

winProperty.bind(createWinLoseBinding(Cell::notMine, Boolean::logicalAnd));

loseProperty.bind(createWinLoseBinding(Cell::isMine, Boolean::logicalOr));

One Ugly Part

The only problem with the win/lose logic is that it isn’t relevant in the time between the reset of the grid for a new game and the first cell click of that game. It needs to be disabled for that time span so we have the following code:

public void reset() {

winProperty.unbind();

winProperty.set(false);

loseProperty.unbind();

loseProperty.set(false);

cells.clear();

initialized = false;

}

This seems a bit clumsy, but the only alternative is to turn the initialized field into a BooleanProperty and then tie it into the BooleanBinding built for the winProperty and loseProperty. But doing this wouldn’t make anything clearer, and the bindings still need to be rebuilt and bound to those properties after the first click.

The Main Class

The Main class is only of interest here because has some code which resizes the window according to the size of the board the game is being played on:

public class MineSweeper extends Application {

public static void main(String[] args) {

launch(args);

}

@Override

public void start(Stage primaryStage) throws Exception {

primaryStage.setTitle("Minesweeper");

BiConsumer<Integer, Integer> screenSizeHandler = (height, width) -> {

primaryStage.setHeight(height);

primaryStage.setWidth(width);

};

Scene value = new Scene(new MineSweeperController(screenSizeHandler).getView());

primaryStage.setScene(value);

primaryStage.show();

}

}

You can see that the Main class passes a BiConsumer to the constructor of the Controller to allow it to change the size of the window. In this way, the main screen Controller needs to have no knowledge of anything outside it’s scope. It has a dependency declared in its constructor that requires that any parent class instantiating the Controller has to provide some sort of screen size handling

The images

If you want to copy this code and run it yourself with changing things, you’ll need the images:

Summary

Once the game is underway, there’s only really two lines of code that are directly executed when a cell is clicked:

if (evt.getButton().equals(MouseButton.SECONDARY)) {

model.isFlagProperty().set(!model.isFlagProperty().get());

} else {

model.clickedProperty().set(true);

}

Everything else is either layout or setup, which largely consists of setting model values and creating bindings between the view and the model. This the essence of programming with JavaFX: virtually all of the JavaFX code is setup - creating the layout, the bindings and the listeners - and it only amounts to a small proportion of the overall code.

Look at where the bulk of the code in this application resides. It’s in the Controllers, after the getView() method. Sure, a lot of it deals with observables and properties, but it deals with them as data, and the way that they are tied back to the GUI is not considered in that code at all.

Another thing to note is just how small the entire application is. The Cell MVC has about 60 lines of code, and the Game MVC has about 100 lines of code. To me, that doesn’t seem like much code at all considering what it does.

Using the MVC design pattern here really allows the code to become easier to understand and to develop. Having a clear picture of exactly what information is needed to make the GUI work is a key step to creating a clean design for the GUI, and the need to define a Model helps to understand that. Having a complete separation between layout and application logic is critical to implementing MVC cleanly, and the result is that a of complexity that you’d have without it just drops out of the application.

In terms of having a multi-layered MVC construction, note how the Game Board MVC has no knowledge of or dependencies on the structure of the the CellView. To the Game Board MVC, and to the MineSweeperView, it’s just a Region. Once the Cells have been instantiated and the CellViews have been passed on to the MineSweeperView, the MineSweeperController only deals with the Cells as gameplay objects. The visual aspect of a Cell can be ignored by the MineSweeperController gameplay logic.