Introduction

Model-View-Controller (MVC), Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) and Model-View-Presenter (MVP) are three of the most common frameworks that you are likely to encounter when working with systems that have a User Interface (UI). It’s really important to understand how these frameworks work, what they achieve, and how to implement at least one of them in the environment that you work in.

I have to say that I struggled with this article for a long time. I worked for years with a pattern that I had assumed was MVC, and felt that it was somehow incomplete. So I added some bits on, and made adjustments that made sense to me. Then I learned that my understanding of “Model” was not the same as the technical definition. That “correct” definition of Model makes MVC more complete, but I’m not really happy that it maps well to JavaFX or any other modern platform.

Who am I to argue with the giants of application framework theory? No one, really. But I can say that my understanding of how to build clean and simple JavaFX has come over nearly ten years of practical experience, working at it pretty much 9-5 every weekday. From that experience, constantly trying improve my approach with each new application, I’ve arrived at what I think is a better solution.

What’s Their Purpose?

These are design patterns. They are standard ways of architecting things to achieve common ends. The advantage to using a design pattern is that they are generally well known and well thought-out, so they are familiar and easy to build and to understand when you encounter them in the real world.

In this particular case, these are different approaches to solve the problem of separating the presentation of data to the user from the actual data and the back-end logic. In this way, the UI becomes much less dependent on the back-end structure (and visa versa) so that changes to either the UI or the back-end don’t require refactoring the other end.

This is a huge concept. Let’s say that you have something like a customer inquiry screen for your application. If the people in charge come to you and say, “We’re going to export all of our customer data out of our main database and use this brand new CRM system instead, from now on you’ll have to populate your screen from the CRM system’s API”, you don’t want to have to mess with your GUI code in order to change the data storage.

Let’s say this CRM system stores the data in a little different way. Perhaps it has a separate field for name suffixes, like “Jr”, “Sr”, “III” or “Esq”. Once again, you don’t want to have to change your GUI to accommodate that, adapting the CRM data to your screen is something that your business logic should handle.

Let’s say the CRM system only allows you to update a customer twice in one day. That error processing should be part of the business logic and handled without changing your main GUI. Maybe there’s a pop-up message when the save fails.

In another scenario, maybe you have several different uses for your logic that require slightly different GUI’s. Perhaps you have an inquiry screen. It uses all the same logic and data, but the entry fields are display only. It would be nice if you could create an inquiry only GUI, and then just connect it up to the same back-end and business logic that your data entry screen uses.

These frameworks should let you handle all of these situations.

Understanding the Terminology

A small amount of time spent searching the web will show you that there’s many different interpretations of what design patterns really mean. Even if you go back to some of the original articles where these patterns were first introduced, there’s a lot of ambiguity and room for interpretation.

So let’s look at the most confusing concept first:

The “Model”

There’s an idea that data should be bundled up with code that is related to it, so that the result is a responsive object rather than just a bunch of data in fields. This is a common concept in OOP system design, and you’ve undoubtedly seen it many, many times. Even if it’s just getters and setters to isolate the internal implementation of the data from it’s outward presentation.

That’s the concept behind “Model” in all of these design patterns. It’s not just the data, but it’s the data handling and business logic as well.

There’s a big issue with the name “Model”, though. While everybody understands that data and associated logic should be packaged together, “Model” implies a very data-centric orientation of this element of the framework. This doesn’t really encompass things like external API calls, data persistence and overall business logic - all of which are supposed to go in the “Model”. We’ll see how this causes problems.

Domain Data vs Presentation Data

“Domain Data” is the under-the-hood representation of the data in your application. Let’s say that you have a database with customers and customer orders. You might have a Broker/DAO that returns the customer name, address and email, along with the date of their last order from your database. That information could come from several tables in the database, and it might be complicated to put it together, but it delivers it to you in a class called CustomerInfo. This class, CustomerInfo is “domain data”.

“Presentation Data”, however, is data that’s been packaged up, configured and prepared for use in the GUI. Let’s go back to CustomerInfo. Perhaps this class has the name divided into firstName and lastName. For your GUI however, you just need a single name element. Something, somewhere has to take the two CustomerInfo fields and transform them according to some business rules into a single data element available to the GUI. Maybe it’s “firstName lastName”, maybe it’s “lastName, firstName” or something else.

Finally, in Reactive JavaFX, the Presentation Data needs to be in some kind of Observable data type. So in our name example this would be a StringProperty.

Business Logic vs Presentation Logic

Most of the time, it’s pretty clear whether a piece of logic needs to be considered the implementation of a business rule, rather than purely an aspect of the View. This would dictate whether or not it belongs in the Model.

Sometimes, it’s not so clear. Let’s go back to that conversion of firstName and lastName into a single name field, and how it’s converted. Is it business logic, or is it simply an aspect of the View?

That can depend. In a lot of cases, it’s purely View. You’ll get the greatest decoupling of the elements by having both firstName and lastName in your Presentation Data, and letting the View decide how to display them. But what if there’s a requirement to display a bunch of names in alphabetical order? Now you might be talking about a business rule. Sorted by firstName or lastName? So maybe, in this case, you need to deal with the conversion in the Business Logic.

Traffic Management

Every framework needs some element to manage how the parts interact with each other, and possibly with other frameworks. There needs to be a component that accepts some signal from the View - possibly containing data - and turning that into an action involving the business logic that’s contained inside the Model. There also needs to be some component that understands about background threads, and has the logic to control them.

How Do These Patterns Work?

The first thing to understand is that all of these patterns have the same goal, to create independence between the business logic and the presentation that the user interacts with. They all have a great deal of similarity, but they have some profound differences in the details.

Let’s look at each of these patterns and try to figure out the best understanding of what they mean.

Your Interpretation May Be Different

Before we start, you should note that there are many, many interpretations of how these patterns work. Google any of them and you’ll find lots of pages that contradict each other, and the longer you look, the more you will find.

For the most part, these patterns were designed long, long ago. Long before web pages, long before Java. If you go back to the earliest discussions about these patterns, you’ll find that they’re highly theoretical.

Martin Fowler’s page on GUI Architectures is a great modern review, but it’s still heavy reading and contains things like this:

So it’s not surprising that virtually everyone using one of these patterns hasn’t actually read one of these technical papers from way back, and they’ve picked it up from some web tutorial, written by someone who picked it up from someone else who hasn’t read one of the original papers either. And, of course, all of these people are trying to adapt it to their platform after reading about someone else’s adaptation on some different platform.

For this discussion, I’ll try to present a description that matches the original, formal definition as much as possible. However, your understanding of these patterns is very likely to be different to what you’ll find in this article.

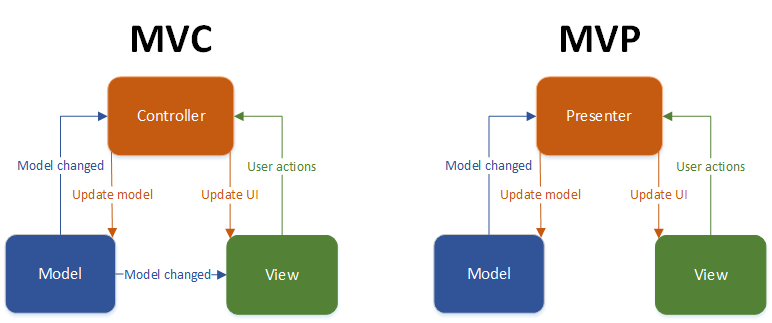

With that in mind, we’ll start with MVP and MVC:

From their diagrams, they look very similar, with the only difference being that in MVC the View gets updates directly from the Model. However, the way that they work is very, very different.

Model-View-Presenter

Model-View-Presenter (MVP) has three components which each have very specific roles:

- The Model

- As previously discussed, the Model has all of the data, and all of the business logic contained within it including service calls and persistence logic. It should also make data available in a state ready to be applied to the View. Calls to databases and external API’s also go in the Model.

- The View

- In MVP the View is supposed to be an entirely passive layout entity containing only static configuration and styling. It contains virtually no decision-making logic of it’s own, and it’s entire purpose is to put data on the screen, and to receive input from the user. Once it gets input from the user, its only role is to pass it on to the Presenter, which will decide how to handle it.

- The Presenter

- The Presenter works hand-in-glove with the View. The Presenter has access (perhaps indirectly) to the View and the inside components of the View and manipulates them to make the View behave as it should. For instance, the Presenter is responsible for placing data from the Model into the View components, and visa versa. The Presenter contains all of the logic for defining how active components like Buttons will behave.

MVP uses the View for pure layout and styling. All other aspects of the GUI are handled via the Presenter. It’s hard to imagine a system where the Presenter and the View are not tightly coupled. The Presenter has to have detailed information about the internal structure of the View in order to configure it. In this respect, it’s probably easiest to treat the Presenter and View as a single component.

The Problem with Model-View-Presenter

The problem with MVP is the intense coupling between the View and the Presenter. It’s hard to imagine a situation where you could do anything less trivial than move a widget around on the screen, or change its styling without needing to make a corresponding change to the Presenter.

The end result is that the View and the Presenter are essentially one object divided into two classes and irrevocably tangle together. This, of course defeats the purpose of using a framework in the first place. This kind of makes MVP useless, in my opinion.

One situation where I could see implementing MVP is if you are married to the idea that FXML somehow gives you an automatic step up towards a framework. In that case, if you are careful, you can implement the FXML file as the View, and then the FXML Controller as the Presenter. Of course, you’ve still just started to implement MVP - which is probably not worth the effort.

Model-View-Controller

In the traditional, non-Reactive, implementation of MVC the View is generally seen as only a consumer of the Model’s data, and the Controller is responsible for taking any updates from the User, and updating the Model.

- The Model

- The Model contains all of the data in the framework. This includes the elements of State, plus any domain objects that are required for the business logic. The Model exposes some “presentation ready” data elements to the Controller and the View. It also contains all of the logic to interface with external parts of the system such as databases or external API’s.

- The View

- The View contains all of the elements of the UI and, unlike the View in MVP, is complete unto itself. There is some mechanism to allow the View to be directly updated from the Model. Perhaps the View has a reference to the Model, and can call getters in the Model (when notified by the Controller), or perhaps the Model has a reference to the View and can call setters in the View (probably not a good design).

- The Controller

- The Controller handles the actions for the GUI. This includes transporting updates from the View to the Model, and handling “events” triggered by user actions.

MVC couples the View to the Model, since it needs to be able to access data elements from it and from the Controller to the View since it needs to get data from the View.

The Problem with Model-View-Controller

The big issue with MVC is when you try to implement it with a reactive GUI. Remember that a reactive application has a data representation of its “State”, which in MVC is stored in the Model. Then the GUI and the data representation of state are kept in lockstep with each other. The GUI changes to reflect changes in the data, and the data changes to reflect actions in the GUI.

However, in MVC the View is allowed to look at and update from the Model, but it’s not allow to update the Model directly. All changes to the Model from the View have to go through the Controller. In JavaFX, this rules out using Bindings from the View Nodes to the Model elements - which is a showstopper.

Now, if you are using JavaFX in a non-reactive way, then MVC may be just the thing for you. But if you are not using JavaFX in a reactive way, then you’re also missing out on a lot of the power of JavaFX - and making a lot of work for yourself.

Model-View-ViewModel

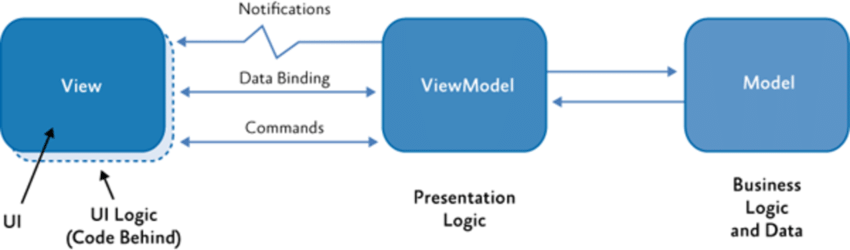

At first glance MVVM appears to be the best match for modern, reactive UI’s as it specifically talks about “binding” to connect the View to the ViewModel.

- The ViewModel

- The ViewModel contains the data in a structure appropriate to bind it to various components of the View. It also contains the functionality to prepare the data in that format (called “Presentation Logic” in the diagram). In order to do this, the ViewModel needs to access to the data elements stored in the Model, and will probably call methods in the Model to initiate data storage and retrieval. Additionally, the ViewModel handles actions triggered by user “events” from the View.

- The Model

- The Model in this pattern potentially leans more towards dealing with application domain data, as the ViewModel handles some amount of the transformation of this data into presentation data. From that perspective, the business logic is split between the Model and the ViewModel, with the Model handling persistence and external API’s.

- The View

- Just as in MVC, the View in MVVM is self-contained and includes not just the layout but styling and configuration of the elements. The big difference is that data elements from the ViewModel are bound to the screen elements. This means that the “State” of the View is accessible to the ViewModel at any given time and there’s no need to provide any functionality to “scrape” the data out of the View to pass it to the ViewModel. At the same time, the ViewModel can update the View simply by changing the value in those data elements bound to the View.

The Problem with Model-View-ViewModel

The big problem with MVVM is that the ViewModel isn’t allowed to see the domain objects, and the Model isn’t allowed to see the presentation objects.

This means that the Model can’t just pass over a CustomerInfo object to the ViewModel and let it figure out what it needs to take out to populate the elements of the presentation objects. No, the Model has to provide some sort of “presentation ready” data to the ViewModel. So if the ViewModel needs customerName, then it has to ask for it and the Model pulls it out of CustomerInfo and sends it as a String.

On top of that, the ViewModel cannot have any business logic. So if customerName is sourced from 5 different fields in CustomerInfo and put together in some particular way which satisfies business rules, then it has to happen in the Model.

And the same conditions hold true in reverse. If the ViewModel wants to request an update to the Customer database, it can’t just pass a new CustomerInfo record to the Model. It has to pass either discrete primitive data elements to the Model, or some DTO-like object instead.

The Elephant in the Room

With all of these frameworks, there’s one implied rule that needs to be openly talked about:

- Domain Objects Can Only Exist in the Model

- Think about it. What would be the point of any of this if you had to change the layout code in your “Customer Inquiry Screen” to accommodate a change in the CustomerInfo object? The same thing goes for the Presenter, Controller or ViewModel. The decoupling requires that CustomerInfo and the all of the business logic that deals with it resides only in the Model.

This leads to the following corollary:

- The Model Has to Present “GUI-Ready” Data Upstream

- Since the Model is the only element that can deal with Domain Objects, it follows that it has to contain the logic that extracts data from the Domain Objects, packages it up in a manner that the Presenter, Controller or ViewModel can deal with it, and provide some way to transfer it out of the Model.

And this has the following consequence:

Everybody Encapsulates “GUI-Ready” Data in a Class

There’s a problem that pops up in the class that creates and holds the presentation data - in MVC it’s the Model, and in MVVM it’s the ViewModel. And that problem is that those classes end up with a massive amount of fields and access methods that get jumbled in with the other functionality of the class. On top of this, all of those public accessor methods become coupling points between that class and the other classes in the framework.

Think about it, if you’re using MVC and you have 30 Property elements that are needed for the View, plus maybe a List or two to support some tables - and if you follow the ordinary practice of having a delegate setter and getter, plus a Property getter for each of those elements then you are going to have 90+ public methods dedicated to just that in your Model. That’s in addition to the business logic and fields to hold domain objects and the rest.

If nothing else it becomes a mess to deal with, and is a pretty clear violation of the “Single Responsibility Principle”.

To get around this issue, composition is used, and the presentation-ready data is placed into its own class which is then a single field in the Model or ViewModel. If you want to have a single method like Model.getCustomerData() that returns a value that can be used by the Controller or the View, then that return value has to be a class that encapsulates presentation-ready data. And that class, for all intents and purposes, is a “Presentation Model”.

What this means, as a practical matter, is that virtually every implementation of these frameworks has 4 components: A Model, a View, one of Controller, Presenter or ViewModel, and a Presentation Model.

This is Where the Problems Occur

A little bit of time spent searching the Web will find lots and lots of sites explaining how MVC works with examples. Virtually without exception, they all explain the Model has data and associated logic, some of them with diagrams that show the Model directly connected to the database. But then, in their example code…

- They Cheat

- The Model has just Presentation Data in it, without any persistence or business logic and they dummy up a Model in the

main()class that has a database call.

or

- They Put Persistence in the Controller

- The Model has just Presentation Data in it, and the Controller has a simple database call that stuffs the Model with data from the database.

In other words, virtually every example that you’ll find, consists of a Presentation Model, View and Controller. No “Model”, as defined by the framework, to be found anywhere. It’s probably because they cannot reconcile the idea of having all these elements of GUI data cohabiting and cluttering up a class with business logic.

To be fair, this is completely logical and reasonable way to handle the “GUI” part of an application. It’s highly intuitive and makes a lot of sense. In fact, A lot of people think that this is what MVC is.

But there’s one issue. What about the business logic, persistence and external API’s?

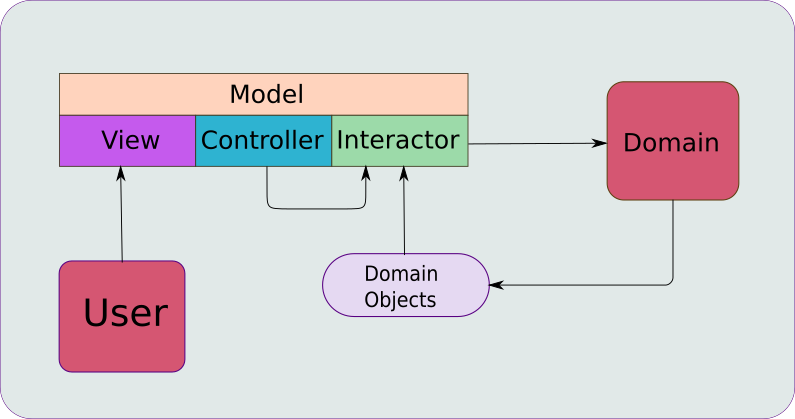

A Better Framework for Reactive Systems: MVCI

As I said earlier, I went on for years misunderstanding the “correct” structure of MVC. My understanding was the the “Model” was simply the “Presentation Model”. In a Reactive design, “Presentation Model” is the data representation of the “State” of the GUI.

In this interpretation, the Model is simply a POJO with the fields composed of Observable objects, suitable for binding to the various properties of the View elements. It’s just a place to gather all of the elements of State together in one object, so that it may be passed around as a single component.

However, with that interpretation, I always felt that there was something missing - the piece that connects it to the back-end of the application. So I needed to add that on, and then build some rules about what goes where and who is responsible for what. The result is something I call Model-View-Controller-Interactor (MVCI) and I’ve found it to be ideal for use in a JavaFX Reactive implementation.

Now, when I go back and look at how those other frameworks are really supposed to work, I can see how they have problems and how my new framework relates to them. And it’s similar in many ways, but it’s also something completely new and different. And, IMHO, it’s better.

Let’s look at the components:

The Model

The Model is really just a POJO, and represents the “State” of the GUI. The fields are, for the most part, Observable objects. This means that they can be Properties, ObservableLists, Bindings or ObservableValues of some sort. In general, every element included in the Model should potentially have some direct relationship to some aspect of the View.

Originally, I was pretty stringent about following the JavaFX “Bean” structure for getters and setters, and having a getter for both the Observable itself and it’s contents. I’m not sure about the need for that any more, and currently I lean towards just having a getter for the Observables themselves. The cost for this is that code in the Interactor, which is the only place that getters and setters for the Observable contents is used, gets a little bigger as it needs to do a get() or set() on the Observables. It also exposes the Observable nature of the data in the Model to the Interactor, which might not be desirable.

I really don’t think that relationships between the data elements in the Model should be established in the Model itself. These relationships generally reflect business rules of some sort, and that kind of logic belongs in the Interactor at all times. My guide has always been, “If you are looking for business logic, it should always be in one place - the Interactor.” This means that if you are looking to understand how two data elements are related, you don’t have to go hunting through the entire framework to find place where they are linked, it will be in the Interactor.

The View

The View handles every aspect of the User Interface and nothing else. Properties of the components of the View are bound to each other and to the Properties in the Model. In this manner, the Model now becomes an accurate representation of the State of the UI.

In Reactive JavaFX, the View layout should be static, but it should behave dynamically in response to changes in the Model. What does this mean? It means that all of the components of the layout are instantiated, configured, styled and composed when the GUI is built. As much as possible, favour controlling visibility over inserting/removing elements from the layout.

Let’s take an example:

Suppose you have an error message that’s going to be displayed on the screen via a particularly styled Label. Most likely, the error message isn’t going to be displayed when the View is first displayed. Put it in the layout anyways, configure and style it, then Bind its Visible and Managed properties to a BooleanProperty in the Model that indicates an error. Let’s say that the error message needs to change its content based on the nature of the error. Bind the Text property of the Label to elements in the Model that indicate the nature of the error.

The Controller

The Controller is the “core” of the framework. It is responsible for instantiating all of the other components and connecting them together. The Controller connects the MVCI construct to the rest of the application as it contains the only methods accessible by any object outside the MVCI construct. Typically, it will have a method with a name like getView() which will return the View which can then be placed inside another layout or Scene.

The Controller is responsible for handling all of the “actions” in the UI. This means that anything more active than simply updating the Model (through bindings in the View) is processed through the Controller. The Controller defines how these actions will be handled, and any threading that might be required. In practice, this means that the Controller will be responding to EventHandlers triggered from the View, and will establish any Listeners on the Model.

The Interactor

The Interactor contains all of the business logic of the framework. This is the class where both the Model and the domain objects co-exist:

- Business Constraints and Connections Between Model Elements

- Often there are connections between fields defined in the Model which are related to business rules. For instance, you might have a

BooleanPropertythat indicates that some combination of otherPropertiesin the Model are invalid. ThisBooleanPropertywould be bound by the Interactor to aBindingthat it constructs. This keeps the business logic inside the Interactor. - Connections to External APIs

- If there are going to be connections to external APIs, then they are going to be in the Interactor.

- Connections to Data Persistence

- Once again, if you are going to have a direct connection to a persistence layer, then they will be in the Interactor.

- Connections to Shared Application Libraries

- In any system with more than one screen, you are likely to have a fair amount of shared business logic or brokers that connect to APIs or persistence libraries. These libraries are likely to return and accept application domain objects.

- Business Logic for Actions

- This is probably the main function of an Interactor: To provide the methods that bring together State, domain data and business rules to make the framework actually do something.

Let go back the the error message example from the “View” section above:

Let’s say there’s a “Save” Button on the GUI and the user clicks it. Since the View properties are bound to the Model, the Interactor immediately has access to the View data through the Model. So “Save” just needs to trigger an action, not transfer any data to the Interactor. The Interactor has some code that checks the data in the Model, maybe does a database lookup and determines that the “Save” function cannot be run with the current data. So it sets an error flag in the Model to true and composes a StringProperty in the Model with a reason. All done.

Why is this Better?

In my opinion, it’s better because each component does one job, and that job matches with its name:

- View

- The View is solely and uniquely responsible for the UX. Nothing more.

- Controller

- The Controller is responsible for “controlling” everything. It’s sets it all up, and then acts as traffic controller for any actions that take place, defining how they will be handled and on what thread. This includes actions triggered by the GUI and through

ChangeListenerson the elements of the Model. - Model

- The Model is the sole repository of the “State” of the UI. It’s just data and has no logic. Since a reference to the Model is held by both the View and the Interactor, the Interactor can directly interact with the “State” of the UI without any intermediary.

- Interactor

- The Interactor is business logic element and, as such, is solely and uniquely responsible for interacting with the outside world (other than the UX).

This structure makes it simple to understand. There’s never any doubt about what code goes where.

In a way this is very similar to the MVC with State split out into its own element and used Reactively. Now the Model from MVC minus State becomes the Interactor, and the View directly interacts with State to keep the View & Model (State) synchronized at all times. The Controller continues to handle actions from the View, but doesn’t contain any business logic and delegates that to the Interactor.

A Simple MVCI Example

Let’s look at a simple example that shows how it all goes together, an application that queries an external API to retrieve weather information for a location.

When it’s running, it looks like this:

The Controller

Here’s the Controller code:

public class WeatherController {

private final WeatherInteractor interactor;

private final WeatherViewBuilder viewBuilder;

public WeatherController() {

WeatherModel viewModel = new WeatherModel();

interactor = new WeatherInteractor(viewModel);

viewBuilder = new WeatherViewBuilder(viewModel, this::fetchWeather);

}

private void fetchWeather(Runnable postFetchGuiStuff) {

Task<Void> fetchTask = new Task<>() {

@Override

protected Void call() {

interactor.checkWeather();

return null;

}

};

fetchTask.setOnSucceeded(evt -> {

interactor.updateWeatherModel();

postFetchGuiStuff.run();

});

Thread fetchThread = new Thread(fetchTask);

fetchThread.start();

}

public Region getView() {

return viewBuilder.build();

}

}

We can see in the constructor that the Interactor and the ViewBuilder are instantiated with the Model as a constructor dependency satisfied by the newly instantiated WeatherModel. In addition, viewBuilder is supplied a Consumer to handle the “Fetch Weather” action.

The “Fetch Weather” action requires connection to an external website and is therefore blocking in nature. That can’t happen on the FXAT, so the Controller creates a Task to handle the threading required.

This controller has exactly one public method other than its constructor, getView(). The method invokes the viewBuilder.build() method to return a Region.

Connecting it to the Application

We can look at the Application class to see how the Controller supplies the connection from the MVCI framework to the rest of the JavaFX application. There’s nothing complex here, as this application just has the one screen, so we can instantiate the Controller and call its getView() method to populate the Scene:

public class WeatherMain extends Application {

public static void main(String[] args) {

launch(args);

}

@Override

public void start(Stage primaryStage) {

primaryStage.setScene(new Scene(new WeatherController().getView()));

primaryStage.show();

}

}

Look at how simple this is. There is zero visibility into the specifics of what the MVC-I construct is going to do.

The Model

The Model is, as expected, just a POJO with a bunch of JavaFX property “beans” :

public class WeatherModel {

private final StringProperty temperature = new SimpleStringProperty("");

private final StringProperty conditions = new SimpleStringProperty("");

private final StringProperty city = new SimpleStringProperty("Nice");

private final ObjectProperty<Image> icon = new SimpleObjectProperty<>();

private final ObservableList<String> cities = FXCollections.observableArrayList();

private final StringProperty units = new SimpleStringProperty("metric");

public String getTemperature() {

return temperature.get();

}

public StringProperty temperatureProperty() {

return temperature;

}

public void setTemperature(String temperature) {

this.temperature.set(temperature);

}

.

.

.

}

I’ve trimmed out most the methods as it just repeats for each Property. That’s one of the strengths of this framework: The Model is almost always just boilerplate and 90% of the code is of no interest to anyone. You can look at those 6 lines of field declarations and you know everything. You don’t need to see the other 60 lines of code with the accessor methods.

What we will see is that each of the elements in the Model has some direct relationship to some aspect of the GUI, which is why it is part of the Model.

The ViewBuilder

Here’s the ViewBuilder. The build() method returns a Region, which is actually a BorderPane under-the-hood. It only has the centre and bottom zones populated. The centre zone is comprised of a weather image and a GridPane with details. There are a VBox and an HBox to give some structure to the layout.

The bottom has a city selection ComboBox and a Button in an HBox. You can see how the onAction() method of the Button invokes the Consumer passed from Controller to fetch the weather, while disabling and enabling the Button at the right times.

public class WeatherViewBuilder implements Builder<Region> {

private final WeatherModel viewModel;

private final Consumer<Runnable> weatherFetcher;

public WeatherViewBuilder(WeatherModel viewModel, Consumer<Runnable> weatherFetcher) {

this.viewModel = viewModel;

this.weatherFetcher = weatherFetcher;

}

@Override

public Region build() {

BorderPane results = new BorderPane();

results.setCenter(setUpCentre());

results.setBottom(setUpBottom(weatherFetcher));

results.getStylesheets().add(Objects.requireNonNull(getClass().getResource("/css/default.css")).toExternalForm());

results.getStyleClass().add("weather-box");

return results;

}

private Node setUpCentre() {

ImageView iconImageView = new ImageView();

iconImageView.imageProperty().bind(viewModel.iconProperty());

iconImageView.setFitWidth(200);

TwoColumnGridPane gridPane = new TwoColumnGridPane();

gridPane.addTextRow("Temperature:", viewModel.temperatureProperty());

gridPane.addTextRow("Conditions:", viewModel.conditionsProperty());

gridPane.setMinHeight(160);

gridPane.setMinWidth(200);

VBox vBox = new VBox(5, TextWidgets.boundStyledText(viewModel.cityProperty(), "heading-text"), gridPane);

HBox hBox = new HBox(10, iconImageView, vBox);

vBox.getStyleClass().add("info-box");

vBox.setPadding(new Insets(6));

return hBox;

}

private Node setUpBottom(Consumer<Runnable> fetchWeather) {

Button button = new Button("Get Weather");

button.setOnAction(evt -> {

button.setDisable(true);

fetchWeather.accept(() -> {

button.setDisable(false);

});

});

ComboBox<String> cityCB = new ComboBox<>();

cityCB.getItems().setAll(viewModel.getCities());

viewModel.cityProperty().bind(cityCB.valueProperty());

ToggleButton unitsToggle = new ToggleButton();

return new HBox(10, cityCB, button);

}

}

The Interactor

Now, let’s look at the Interactor:

public class WeatherInteractor {

private final WeatherModel viewModel;

private final WeatherFetcher weatherfetcher = new WeatherFetcher();

private WeatherData weatherData;

public WeatherInteractor(WeatherModel viewModel) {

this.viewModel = viewModel;

viewModel.setCities(Arrays.asList("London", "Paris", "Nice", "Hong Kong", "New York", "Las Vegas"));

}

public void checkWeather() {

weatherData = weatherfetcher.checkWeather(viewModel.getCity());

}

public void updateWeatherModel() {

viewModel.setTemperature(weatherData.getTemperature());

viewModel.setConditions(weatherData.getConditions());

viewModel.setIcon(weatherData.getWeatherImage());

}

}

The constructor holds any initialization of the Model that’s required. In this case, it’s the list of cities that weather can be checked for. It’s clear that this list is absolutely “business logic” for this application, and the responsibility for initializing it belongs here, in the Interactor.

The two public methods are involved in the “Fetch Weather” action, and are called from the Controller via its Task. The first method, checkWeather() is intended to be called from a background thread. The second is intended to be called on the FXAT, and therefore, can update the Model.

We’re using an internal library, WeatherFetcher, as a “broker” or “service” to query the web to get the weather. This broker returns WeatherData, which is a “domain” object. If this was a bigger application with lots of different functions and screens, then there would be a entire application layer with brokers and utilities to perform functions and apply business logic shared across the entire application. But here we just have a single broker, which we’re not going to look into at all since it’s not relevant to the MVCI framework.

That’s an important point. WeatherFetcher could be horribly complex, with thousands of web calls and millions of lines of code. And WeatherData could have hundreds and hundreds of fields with forecasts, historical data, wind speeds, barometric pressures and so on. Most of this is irrelevant to our application, which is just to fetch the current temperature and overall conditions for a handful of specific cities. So, while the code in the WeatherFetcher could be considered to be “business logic”, it’s not business logic related specifically to this application, so it doesn’t belong in the Interactor. Which is why it’s in a separate service, and we don’t even have the code for it included in this example. What we do have is the business logic for calling WeatherFetcher for our cities, and extracting the data that we do need for our application from WeatherData.

Lastly, you can see how the domain object is stored in the Interactor as a field. This way it can be populated on the background thread and then accessed on the FXAT. Obviously, with two threads accessing the same data, there are concurrency issues that might need to be addressed. In this particular example, there is no way that the we can have problems because the structure around the action prevents multiple concurrent Button clicks.

The Value in the Framework

Now we have a concrete example, let’s look at how this framework adds value to the application.

It really just does one important thing: It reduces coupling.

How much coupling do we have?

- The View has no public methods other than those inherited from

Region. - Public methods are a primary indication of coupling. Here we have absolutely zero public methods specific to the View, so there’s no coupling at all in this manner. This means that there are no dependencies on the View!

- The View’s only dependencies are declared in its constructor.

- The View is dependant on the Model and the

Consumerpassed to it from the Controller. The View has no knowledge of the existence of either the Controller or Interactor. - The Interactor’s only dependency is on the Model.

- The Interactor has no knowledge of the View or the Controller. It has dependencies on the structure of the Model, but that’s it.

- The Controller has dependencies on the Interactor.

- Since the Interactor has two public methods that the Controller needs to call, there are dependencies there that the Interactor needs to satisfy.

- The Controller might have dependencies on the Model.

- While this example doesn’t have any Controller dependencies on the Model, it’s possible that it could. For instance, we might put a

ChangeListeneron some value in the Model. - The View has no coupling on the data in the Model, Just its structure.

- In this example, the

Listof cities is populated by the Interactor, and then loaded into theComboBoxin the View. The View doesn’t have any logic dependant on the contents of thatList. If we wanted to create such a dependency, we’d have to replace theListwith something like anEnum, so that the possible values are now part of the structure of the data, not it’s contents.

Obviously, in any non-trivial system there has to be at least some level of coupling if the system is going to be functional. In MVCI the Model is the key component of coupling, as all three of the other components of the framework are dependent on it.

Swapping Out Components

I find that a mental exercise that’s helpful to understand the impact of coupling is to imagine replacing the View or the Interactor with something fantastically different, just to see what the impact would be on the system.

What if we replaced the View from a simple screen to a “Weather Experiencing Chamber?” Imagine you walk into a room and there are a bunch of buttons on the wall, one for each city, and when you hit one it then changes the temperature in the room and blows air, or showers water on you, or turns on a fog machine. Things like that.

What would you need to change in the rest of the system to make it work? Really, nothing. The UX is completely divorced, decoupled if you like, from the mechanics of fetching the data. You still need a list of cites, and you still need to update the Model with the selected city and trigger the action. And you still need to respond to the changes in the Model that hold the weather information.

Now, let’s look at it the other way around. What if we now have a “Weather Setting” system, instead of a “Weather Fetching” system. Pick a city, set the temperature and click a Button. Now our system of weather controlling satellites changes the temperature in Paris. In this case, we’ll need to change the GUI so that the temperature is an input, not an output. The Interactor can be changed with a new Interactor that has an interface to our satellite network that controls the weather. The Model does not need to change, nor does the Controller. The change to the GUI is minimal, and isn’t particularly tied to the functionality contained in the Interactor.

This is Scalable

There’s nothing that says that the Region returned by the Controller’s getView() method has to be the root of a Scene created by Application.start(). It’s independent, so you could put it into some other layout. You can build complete “View–>Database” components that you can implement anywhere. From a Menu, in a Dialog, or as an element of any layout.

It’s also possible to create an MVCI with external dependencies by making them constructor parameters of the Controller. Let’s say you have a sub-screen that will become a Region in a larger layout. There’s a subset of the larger screen’s Model that applies to this sub-screen. Pass this subset of the Model to the Controller of the sub-screen in its constructor, and then use that to initialize the sub-screen’s Model.

In the same way, you can also make functional dependencies in the sub-screen. Let’s say that this sub-screen is the piece that has the “Save” Button. Create a constructor parameter in the sub-screen’s Controller to accept a Runnable from parent screen. Depending on the nature of the sub-screen, it may be possible to create it without an Interactor, delegating those operations to the parent screen’s Interactor.

Conclusion

In my opinion, MVCI is much more intuitive and logical structure for creating Reactive JavaFX applications than any of the three frameworks generally in use. The “Model” is now data-centric, as everyone expects, and the business logic and back-end interaction is handled by something with an appropriate name, “Interactor”.

My experience using this framework is that it is a highly effective approach for any Reactive application. It’s easy to envision a large system with many screens, menus and functions as a network of MVCI constructs, all connected to each other via their Controllers. At the back-end, they can all share a common library of Brokers, DAO’s and Services via their Interactors.

At the very least, MVCI takes one of the most common misinterpretations of MVC and supplies the missing component to turn it into a complete framework that achieves the goal of MVC.