Introduction

OK, first off I know I’m swimming against the stream here, and at odds with things like this found in some of the tutorial pages from Oracle for JavaFX:

JavaFX enables you to design with Model-View-Controller (MVC), through the use of FXML and Java. The “Model” consists of application-specific domain objects, the “View” consists of FXML, and the “Controller” is Java code that defines the GUI’s behavior for interacting with the user.

This is really what we’re going to focus on, how this is wrong, and how to do it right.

I think that if you want a more definitive discussion of MVC, you can’t do better than Martin Fowler’s Article. It’s pretty abstract and can be heavy reading, but he gets it right. Here’s his intro to MVC:

Probably the widest quoted pattern in UI development is Model View Controller (MVC) - it’s also the most misquoted. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve seen something described as MVC which turned out to be nothing like it.

I think the quote from the Oracle tutorial is a perfect example of the problem he mentions.

The Structure of MVC

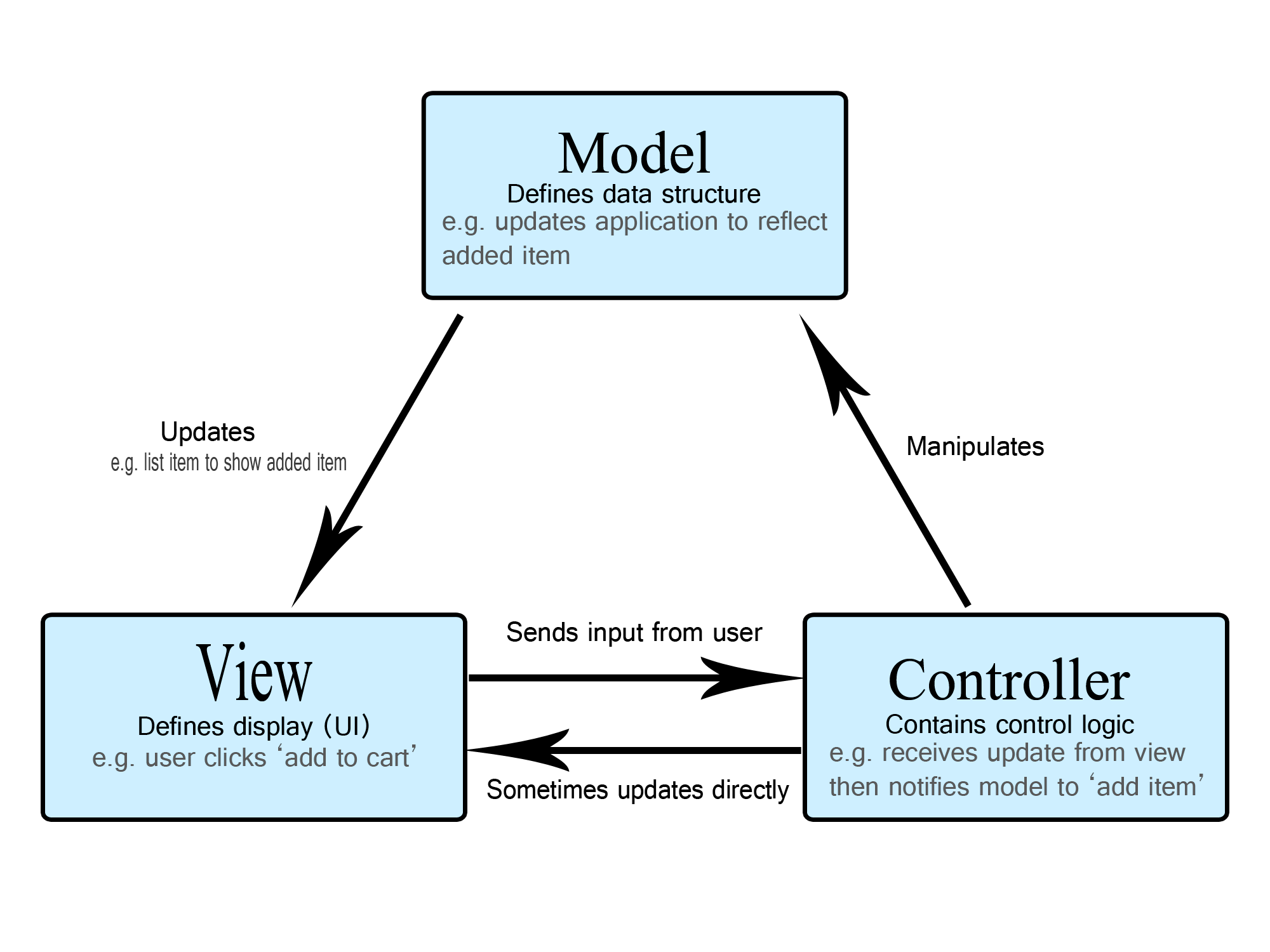

Before we can go any further, let’s look at the parts of MVC and what they do. First, here’s a diagram from somewhere out in the web:

This diagram shows a particular use case (user adds something to a “cart”), but has the essentials down.

- View

- The View is the GUI. It’s the only part of the framework that the user interacts with.

- Controller

- The Controller’s job is to turn user input into actions. It also is the part that interacts with the other GUI parts of your application.

- Model

- The Model is the data and the business logic. Note that the “data” comes in two parts: Presentation Data and Domain Data. The Model is the only component that deals with Domain Data, and a big part of its job is to keep Domain Data away from the View.

What the View Does

The View is layout, but it’s also much more than that in MVC. It’s an independent element that handles all the user interaction.

Let’s take a look at some of the things that the View is solely responsible for:

- Layout

- Styling and configuration

- Connections between layout elements

- Animations

- Data binding to the Presentation Model

- Detecting user interactions such as mouse clicks and keystrokes

- Enabling and disabling layout elements

- Triggering actions

- Responding to changes in the Presentation Model

I don’t think that there’s anything controversial about this list. All of these items are clearly the responsibility of the View in an MVC framework.

If I was building an application without FXML, these are all things that I’d put into my View or my ViewBuilder (which creates the View). For every element of the layout, I’d configure and style it and I’d bind it to the Presentation Model if necessary. Any user interactions would be defined and I’d create EventHandlers for Buttons, Toggles and other things might generate Events.

Most importantly though, no other element of the framework would have any knowledge of the inner structure of the View. There’s zero dependencies on any aspect of the implementation of the View. It’s a “black box” to the rest of the framework.

Now let’s look at how we’d do it with FXML…

We can do the three two items with the FXML file, but that’s about it. The rest of the responsibilities have to be handled by the FXML Controller.

But if the FMXL Controller is doing things like animations and binding Node value properties to the Presentation Model - things that are absolutely the sole responsibility of the View, then what role is the FXML Controller really playing?

It’s pretty obvious, when you look at it this way, that the FXML Controller is actually part of the View.

Back to That Oracle Quote

I’ll repeat it again here:

JavaFX enables you to design with Model-View-Controller (MVC), through the use of FXML and Java. The “Model” consists of application-specific domain objects, the “View” consists of FXML, and the “Controller” is Java code that defines the GUI’s behavior for interacting with the user.

The big problem that we have here are their definitions of the parts of MVC. First:

The “Model” consists of application-specific domain objects

Well, yes, the Model does contain domain objects, but it also contains the Presentation Model and the application logic.

the “View” consists of FXML

Except that the FXML file simply describes the layout, styling and some configuration. This is not a View, this just layout.

and the “Controller” is Java code that defines the GUI’s behavior for interacting with the user

This is just dead wrong. That’s not role of the Controller in MVC, but it is the role of the FXML Controller as part of the View.

Separation of Concerns

Every time I ask someone what they think the value is of FXML (aside from using SceneBuilder) they’ll inevitably respond with:

It ensures separation of concerns.

It must be out there in some popular tutorial somewhere.

Well, to be sure, separation of concerns is an awesome concept. Where I came from we called it “loose coupling”, but it’s all the same, really. We should all strive to have loose coupling between the components of our applications. It’s main purpose of using a framework like MVC - to keep the business logic far, far away from the GUI and visa versa.

But does FXML give you “separation of concerns?”

Well, it does split the layout from the other parts of the View. So that’s something.

But if you treat the FXML Controller as an MVC Controller, then you immediately start to squash all of those concerns together again. This is because the FXML Controller is full of View stuff, and the MVC Controller is supposed to be full of action stuff. Now you have your View stuff sitting in the same place as your action stuff and it very quickly gets hopelessly entangled.

And then it gets worse.

It’s that “The Model consists of domain objects” bit from the Oracle tutorial. Many FXML programmers think that they’ve made a “Model” when they’ve created a few POJO domain objects. So they’ve created a “Customer” object, and maybe an “Order” object and these will hold the data that’s retrieved from the database, and that’s it - they’re done - Model created.

But where does the application logic go??????

And, you know, there’s only one place to put it. The FXML Controller!

And what about the Presentation Model? It becomes fields in the FXML Controller.

And where do those domain objects get stored? Once again…as fields in the FXML Controller.

So off they go, and now there’s database access code sitting in the FXML Controller - probably in some code that defines an EventHandler for a Button.

You can’t get more coupled than that.

The result is that they’ve created a monolithic, single-class application with everything muddled together. This isn’t an exaggeration, virtually every example of an FXML application that you’ll find out there on the internet does exactly this.

But there’s separation of concerns! The layout is tucked away in the FXML file!

How It Should Look

The key thing to understand is that the FXML and the FXML Controller, together with the FXML Loader, create the View. It’s that simple.

You’re on your own to create the Controller and the Model, and you need to understand the framework if you’re going to be able to do it.

Let’s take a look at a simple MVC application and see how the parts work together. I think that FXML complicates the issue at the start, so I’ll just create a Region subclass to be my View, and then we’ll look at how you’d implement FXML later on.

Let’s look at the View first:

public class View extends VBox {

private final Model.PresentationModel viewModel;

private final BooleanProperty showProgress = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

private final Consumer<Runnable> actionHandler;

public View(Model.PresentationModel viewModel, Consumer<Runnable> actionHandler) {

this.viewModel = viewModel;

this.actionHandler = actionHandler;

initializeLayout();

}

private void initializeLayout() {

getChildren().addAll(createTopBox(), createButton());

setPadding(new Insets(30));

}

private Node createButton() {

Button button = new Button("Start");

button.setOnAction(evt -> {

showProgress.set(true);

button.setDisable(true);

actionHandler.accept(() -> {

showProgress.set(false);

button.setDisable(false);

});

});

return button;

}

private Region createTopBox() {

StackPane results = new StackPane();

results.getChildren().addAll(createDataBox(), createProgressIndicator());

return results;

}

private Node createDataBox() {

Label prompt = new Label("Number of Cycles:");

prompt.getStyleClass().add("label-text");

HBox inputBox = new HBox(6, prompt, createTextField());

inputBox.setAlignment(Pos.CENTER);

VBox results = new VBox(20, inputBox, createDataLabel());

results.setAlignment(Pos.CENTER);

results.visibleProperty().bind(showProgress.not());

return results;

}

@NotNull

private Label createDataLabel() {

Label dataLabel = new Label();

dataLabel.textProperty().bind(viewModel.theResultProperty());

dataLabel.getStyleClass().add("data-text");

return dataLabel;

}

private Node createTextField() {

TextField textField = new TextField();

TextFormatter<Long> textFormatter = new TextFormatter<>(new LongStringConverter());

textField.setTextFormatter(textFormatter);

textField.setMaxWidth(120.0);

textFormatter.valueProperty().bindBidirectional(viewModel.cycleCountProperty());

return textField;

}

private Node createProgressIndicator() {

ProgressIndicator progressIndicator = new ProgressIndicator();

progressIndicator.progressProperty().bind(viewModel.progressProperty());

progressIndicator.setMinSize(200, 200);

progressIndicator.visibleProperty().bind(showProgress);

progressIndicator.visibleProperty().addListener(observable -> {

if (progressIndicator.isVisible()) {

Transition transition = new Transition() {

{

setCycleDuration(Duration.millis(2000));

}

@Override

protected void interpolate(double v) {

progressIndicator.setOpacity(v);

}

};

transition.play();

}

});

return progressIndicator;

}

}

It’s just a VBox with a StackPane above a Button. In the StackPane are a ProgressIndicator and HBox holding a Label and a TextField. Either the ProgressIndicator or the HBox is visible at any given time, but never both at the same time.

Now, let’s look at the Model:

public class Model {

private final PresentationModel presentationModel = new PresentationModel();

private String domainObject = "Nothing Yet";

public Model() {

presentationModel.setTheResult(domainObject);

}

void doSomethingComplicated(BiConsumer<Long, Long> progressUpdater) {

for (long idx = 0; idx < presentationModel.getCycleCount(); idx++) {

try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

progressUpdater.accept(idx, presentationModel.getCycleCount());

}

domainObject = "Something was found";

}

void integrateComplicatedResults() {

presentationModel.setTheResult(domainObject);

}

public PresentationModel getPresentationModel() {

return presentationModel;

}

public static class PresentationModel {

private final DoubleProperty progress = new SimpleDoubleProperty(0.0);

private final ObjectProperty<Long> cycleCount = new SimpleObjectProperty<>(5L);

private final StringProperty theResult = new SimpleStringProperty("");

public double getProgress() {

return progress.get();

}

public DoubleProperty progressProperty() {

return progress;

}

public void setProgress(double progress) {

this.progress.set(progress);

}

public long getCycleCount() {

return cycleCount.get();

}

public ObjectProperty<Long> cycleCountProperty() {

return cycleCount;

}

public void setCycleCount(long cycleCount) {

this.cycleCount.set(cycleCount);

}

public String getTheResult() {

return theResult.get();

}

public StringProperty theResultProperty() {

return theResult;

}

public void setTheResult(String theResult) {

this.theResult.set(theResult);

}

}

}

And the Controller:

public class Controller {

private final View view;

private Model model = new Model();

public Controller(long initialCycleCount) {

model.getPresentationModel().setCycleCount(initialCycleCount);

view = new View(model.getPresentationModel(), this::startSomethingBig);

}

private void startSomethingBig(Runnable postRunGUIAction) {

Task<Void> bigTask = new Task<Void>() {

@Override

protected Void call() {

model.doSomethingComplicated(this::updateProgress);

return null;

}

};

bigTask.setOnSucceeded(evt -> {

model.getPresentationModel().progressProperty().unbind();

model.integrateComplicatedResults();

postRunGUIAction.run();

});

Thread bigTaskThread = new Thread(bigTask);

model.getPresentationModel().progressProperty().bind(bigTask.progressProperty());

bigTaskThread.start();

}

public View getView() {

return view;

}

}

Here’s the Main class, and you can see how it interacts with the Controller to get things running:

public class Main extends Application {

@Override

public void start(Stage stage) throws Exception {

Scene scene = new Scene(new Controller(6L).getView());

scene.getStylesheets().add(getClass().getResource("/css/default.css").toExternalForm());

stage.setScene(scene);

stage.show();

}

}

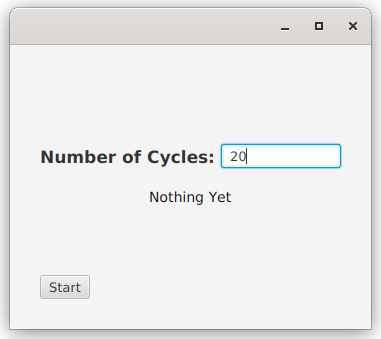

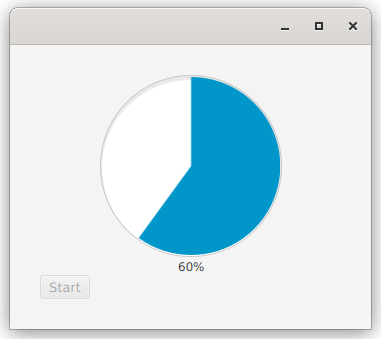

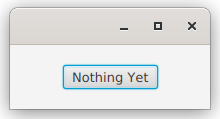

When it runs, it looks like this at first:

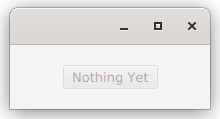

When the “complicated process” is running, it looks like this:

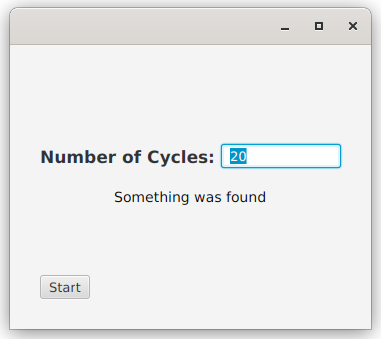

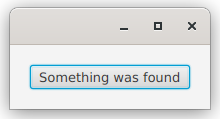

And when it’s all done, it looks like this:

The View class is clearly doing all of the View stuff and nothing but the View stuff. It handles the layout, the View related Button interaction, styling, the configuration of the TextField and binding to the Presentation Model. I even put a fade-in transition on the ProgressIndicator so that you could see how it’s all handled by the View.

The View reveals nothing of its inner workings to any of the other components.

The View has only two dependencies, and they are clearly declared in its constructor: it needs the Presentation Model, and the action handler for the Button (or whatever triggers the action). It takes a Consumer<Runnable> for this action handler, because it needs to perform the cleanup of the GUI after the action has completed. Note that there’s nothing in this action handler that requires the GUI element to be a Button, or even something that generates an ActionEvent. It could be a mouse-over or a keystroke, for example.

The Model is very specifically designed and named in this example to make the intent of the structure clear. The Presentation Data is split out into an enclosed class called Model.PresentationModel, and instantiated into a field called presentationModel. There’s a field called domainData, to make a point about how domain data can be handled.

However, the PresentationModel is split out so that it can be passed to the View without the need to expose all of the other public methods of the Model to the View. In this way, the View is ignorant of the Model itself, and only has knowledge of the PresentationModel on which it depends.

The Controller does just what it is supposed to do, it turns the user interaction into an action. That’s the Controller.startSomethingBig() method. It handles the threading, and provides the connection back to the View (through the Presentation Model) to handle the progress monitoring of the process.

There’s also a constructor parameter for the Controller, to illustrate how the other parts of the GUI would interact with each other through their Controllers. In this case, it’s just the Application class itself, but you get the idea.

One Small Issue

If you are being technically nit-picky (and there’s nothing wrong with that), you’ll notice that this isn’t quite MVC.

In MVC, the View is allowed to read from the Presentation Model directly but it’s not allowed to update it directly. In this example, we’re using bi-directional binding to connect the TextField value to the Presentation Model. That means that anything typed in by the user, immediately updates the Presentation Model without the intervention of the Controller.

Honestly, I don’t know a way around this that isn’t really clumsy. That quote from Martin Fowler’s website continues with:

Frankly a lot of the reason for this is that parts of classic MVC don’t really make sense for rich clients these days.

MVC does seem to be aware of binding-like capabilities, but it predates the JavaFX Reactive library of Observables, Properties and Bindings by decades. So, I think that in this respect we’ll have to accept that JavaFX works best with something that’s close to MVC, but not quite MVC.

In any case, nothing about the structure of this example, using the bi-directional binding, compromises the fundamental goal of MVC - which is to provide for loose coupling between the View and the application logic. So I think we’re still good here.

Cleaning This Up a Bit

This example was very deliberately designed to point out the MVC structure. There’s a class called “Controller”, another called “Model” and one called “View”. Model has an encapsulated class called “PresentationModel” and a field called “domainData” so that you can see how Presentation Data is different from the Domain Data.

But there’s a problem with having a View that extends VBox. There’s nothing stopping the Controller from defining its view field as VBox, and then, if we were to change the structure of the View class, we’d have to modify the Controller class as well.

It’s far better to have “Builder” for the View that returns something very generic like Region. It wasn’t done this way originally, because then we’d have a class called ViewBuilder instead of View. But now you’ve seen it the first way, we can refactor this. Here’s the ViewBuilder:

public class ViewBuilder implements Builder<Region> {

private final Model.PresentationModel viewModel;

private final BooleanProperty showProgress = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

private final Consumer<Runnable> actionHandler;

public ViewBuilder(Model.PresentationModel viewModel, Consumer<Runnable> actionHandler) {

this.viewModel = viewModel;

this.actionHandler = actionHandler;

}

public Region build() {

VBox results = new VBox(10);

results.getChildren().addAll(createTopBox(), createButton());

results.setPadding(new Insets(30));

return results;

}

private Node createButton() {

Button button = new Button("Start");

button.setOnAction(evt -> {

showProgress.set(true);

button.setDisable(true);

actionHandler.accept(() -> {

showProgress.set(false);

button.setDisable(false);

});

});

return button;

}

private Region createTopBox() {

StackPane results = new StackPane();

results.getChildren().addAll(createDataBox(), createProgressIndicator());

return results;

}

private Node createDataBox() {

Label prompt = new Label("Number of Cycles:");

prompt.getStyleClass().add("label-text");

HBox inputBox = new HBox(6, prompt, createTextField());

inputBox.setAlignment(Pos.CENTER);

VBox results = new VBox(20, inputBox, createDataLabel());

results.setAlignment(Pos.CENTER);

results.visibleProperty().bind(showProgress.not());

return results;

}

@NotNull

private Label createDataLabel() {

Label dataLabel = new Label();

dataLabel.textProperty().bind(viewModel.theResultProperty());

dataLabel.getStyleClass().add("data-text");

return dataLabel;

}

private Node createTextField() {

TextField textField = new TextField();

TextFormatter<Long> textFormatter = new TextFormatter<>(new LongStringConverter());

textField.setTextFormatter(textFormatter);

textField.setMaxWidth(120.0);

textFormatter.valueProperty().bindBidirectional(viewModel.cycleCountProperty());

return textField;

}

private Node createProgressIndicator() {

ProgressIndicator progressIndicator = new ProgressIndicator();

progressIndicator.progressProperty().bind(viewModel.progressProperty());

progressIndicator.setMinSize(200, 200);

progressIndicator.visibleProperty().bind(showProgress);

progressIndicator.visibleProperty().addListener(observable -> {

if (progressIndicator.isVisible()) {

Transition transition = new Transition() {

{

setCycleDuration(Duration.millis(2000));

}

@Override

protected void interpolate(double v) {

progressIndicator.setOpacity(v);

}

};

transition.play();

}

});

return progressIndicator;

}

}

The changes here are that instead of extending VBox this class now implements Builder<Region> and the initializeLayout() method has been renamed to build(), made public and returns Region. It’s also no longer called from the constructor. Everything else in the class remains exactly the same.

Now the new Controller class:

public class Controller {

private final ViewBuilder viewBuilder;

private Model model = new Model();

public Controller(long initialCycleCount) {

model.getPresentationModel().setCycleCount(initialCycleCount);

viewBuilder = new ViewBuilder(model.getPresentationModel(), this::startSomethingBig);

}

private void startSomethingBig(Runnable postRunGUIAction) {

Task<Void> bigTask = new Task<Void>() {

@Override

protected Void call() {

model.doSomethingComplicated(this::updateProgress);

return null;

}

};

bigTask.setOnSucceeded(evt -> {

model.getPresentationModel().progressProperty().unbind();

model.integrateComplicatedResults();

postRunGUIAction.run();

});

Thread bigTaskThread = new Thread(bigTask);

model.getPresentationModel().progressProperty().bind(bigTask.progressProperty());

bigTaskThread.start();

}

public Region getView() {

return viewBuilder.build();

}

}

The main change here is that Controller.getView() now delegates to ViewBuilder.build().

Implementing FXML

At this point it should be clear that the nature of the View has been completely isolated from the Controller and the Model, and we can implement it any way we want - just so long as we can use the PresentationModel and the actionHandler that come from the Controller.

This means we could even implement it as FXML! So that’s what we’re going to do.

I’m not going to invest a lot of time and effort into creating a cool design that has all of the functionality of the original View in FXML. We just need something that will work. I’m also not installing SceneBuilder, so I’m hand creating a simple FXML and it’s going to be absolutely minimal.

The FXML File:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<?import javafx.scene.control.Button?>

<?import javafx.scene.layout.BorderPane?>

<BorderPane fx:id="borderPane" xmlns="http://javafx.com/javafx/19" xmlns:fx="http://javafx.com/fxml/1">

<center>

<Button fx:id="button"></Button>

</center>

</BorderPane>

Pretty simple, just a button in a BorderPane. I’m not doing any styling here either, it’s pure layout. We have fx:id for both the BorderPane and the Button, so we’ll do the rest in the FXML Controller:

public class FxmlController implements Initializable {

private final Model.PresentationModel viewModel;

private final Consumer<Runnable> actionHandler;

@FXML

BorderPane borderPane;

@FXML

Button button;

public FxmlController(Model.PresentationModel viewModel, Consumer<Runnable> actionHandler) {

this.viewModel = viewModel;

this.actionHandler = actionHandler;

}

@Override

public void initialize(URL url, ResourceBundle resourceBundle) {

button.textProperty().bind(viewModel.theResultProperty());

borderPane.setPadding(new Insets(20));

borderPane.setMinWidth(200);

button.setOnAction(evt -> {

button.setDisable(true);

actionHandler.accept(() -> {

button.setDisable(false);

});

});

}

}

The only component of the MVC structure that we need to change is the ViewBuilder:

public class ViewBuilder implements Builder<Region> {

private final Model.PresentationModel viewModel;

private final Consumer<Runnable> actionHandler;

public ViewBuilder(Model.PresentationModel viewModel, Consumer<Runnable> actionHandler) {

this.viewModel = viewModel;

this.actionHandler = actionHandler;

}

@Override

public Region build() {

FXMLLoader loader = new FXMLLoader(ViewBuilder.class.getResource("/fxml/view.fxml"));

loader.setController(new FxmlController(viewModel, actionHandler));

try {

return loader.load();

} catch (IOException e) {

return new BorderPane();

}

}

}

When it starts up, it looks like this:

While the process is running, it looks like this:

And ends up like this:

Key Take-Aways

First, and most importantly, is that the FXML based View is way different from the hand coded View, but NOTHING needed to be changed in the Controller or the Model. The coupling is completely defined by the constructor parameters of the ViewBuilder, and those did not change.

This is super important to understand because it is the entire point of MVC.

Secondly, the FXML based View doesn’t display or allow the user to change the cycle count, nor does it use the progress property. This is OK. There’s no rule that says that every possible View has to use the entire data set in the Presentation Model. Perhaps we just want a minimalist widget to stick in the corner of a screen - it’s a valid implementation of the View component.

Third, just as with the hand coded View, there’s no need, or even temptation, to put calls to external services or API’s in the View code. This FXML Controller exists solely to work with the FXML file to create the View. Nothing more.

Finally, the fact that this View is FXML is utterly irrelevant to the rest of the MVC framework. It doesn’t change the structure of the framework, and it doesn’t change the approach.

And that’s how you achieve “separation of concerns” with FXML.