Introduction

A while back, there was a question posed on StackOverflow.com that asked about how to run parallel processing to speed up the rendering of a Mandelbrot set in a JavaFX application. Presumably, the core problem was the the rendering was taking too long and the OP was looking for a way to speed it up.

The complete code was posted in the question.

It turns out that the primary problem was probably fairly easy to fix by moving a single line of code, but it was also possible to improve the performance by introducing a Parallel Stream into the calculation.

However…

Beginner Coding Problems

The original Java code was fairly typical of beginner JavaFX code. In other words, a bit of a mess.

First, about that:

Personally, I don’t feel any great emotional attachment to any code I write, and I tend to view any critisism of my code as a commentary on the code or, at most, on my coding ability at the time that I wrote it. Coding is a skill, and as such we can all hope to improve with practice. Beginners, by definition, make beginner mistakes and it is to be expected that much of their code will be, “a bit of a mess”. None of the comments in this article are about the coder, but just about the code.

With that said, let’s look at the kind of problems you’ll find in beginners’ code:

- Violations of “Don’t Repeat Yourself” (DRY)

- This is something that sneaks into JavaFX fairly easily if you don’t watch out. There’s lots of boilerplate in JavaFX, and you can find yourself doing the same thing over and over.

- Violations of the “Single Responsibility Principle” (SRP)

- Not so much a JavaFX issue, but something that beginners just don’t seem to follow. In this case, it may have help covered up the original problem.

- Not Using Proper Layouts

- JavaFX has a full set of useful layout classes to make it easy to design screen layouts that make sense. Beginners seem to like to ignore them and use

AnchorPaneeverywhere and the set the X & Y offsets of all theNodesinside them. I’m baffled by this. - Not Handling Threading Properly

- Everyone “knows” that you don’t run long tasks on the FXAT, yet all beginners do this time and time again.

- Unaware of Useful Classes

- This is super common. Even experienced JavaFX programmers are constantly learning of useful classes that they never knew existed. In many cases, these classes make it simple to do things that would otherwise be complex or tedious. The JavaFX toolbox is huge, and it takes a while to learn your way around it.

- Bad Naming

- Once again, this is super common. Naming things is hard. At this point I still don’t understand why the original Java code calls the TextField that controls the maximum iterations,

typeIter. The “Iter” part I get, but “type”?

Kotlin

Nowadays, I really prefer to do as much as possible in Kotlin. It’s really a great mix with JavaFX, as it works “out of the box” and has lots of tools to handle the boilerplate that you can get bogged down in.

For this project, I took the Java code and let IntelliJ Idea convert it to Kotlin for me. This gives OK results, but the code does look more like Java code written in Kotlin than Kotlin code. So some work was needed to clean it up a little bit.

The final Kotlin code was about 300 lines, compared to the original Java code at nearly 500 lines. A lot of this is just Kotlin goodness, but there was also a lot of refactoring which reduced the code size considerably. In general, less code is better code, and I think that holds here.

Feature Changes

During the course of this cleanup, some of the functionality of the application was changed:

- Removal of the “Save” Function

- Even still as Java, I had problems with this feature as it wouldn’t compile and resolve a dependency related to

SwingFXUtils. At first I just wanted to get it run so I could see it in action, and I didn’t care about saving, so I just commented it out. Later, I still didn’t care about saving so I removed it. - Rendering as a Background Task

- Even at its fastest, the rendering could take a couple of seconds to complete. This meant that it had to be implemented on a background thread via

Task. - Handling Clicks and Keystrokes While Rendering

- It became clear that the user was very likely to click or press keys while the rendering was in progress. Not to mention resizing the window which generated multiple events that would trigger rendering. A mechanism was developed to store up the changes and then run them automatically when the rendering was complete, then triggering another rendering.

- Parallel Processing for Rendering

- Even with the initial problem corrected, it could still take up to 5 seconds to complete a rendering if the resolution and zoom were sufficiently high. Parallel streaming was implemented to improve the performance by a factor of about 4 times.

- Status Display

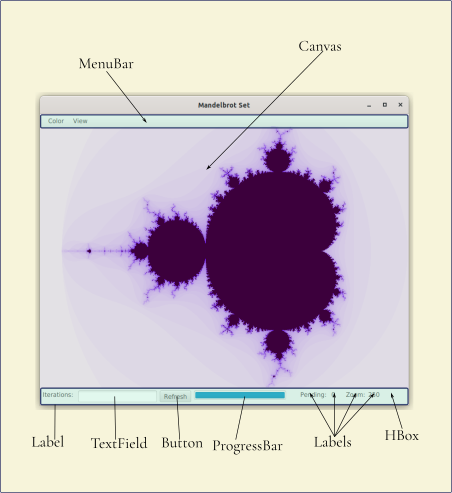

- Elements were added to the display to show the progress of the current render, number of clicks and keystrokes pending, and the current zoom level.

- Proper Handling of the Keystrokes

- This allows the TextField and Button that control the resolution to be on-screen at all times.

The Code

The code for both the Java and Kotlin versions can be found here. I had to move it out because this article was just getting too big with it included.

Alternatively, you can get the complete source code on GitHub, here.

Notes on the Refactoring

General Notes

As seems normal when comments are used, the comments in the Java code were either really obvious or meaningless to me. When my reaction to a comment in code is “Duh?”, or “What?” I usually just delete them and never think about them again. Otherwise they just take up valuable screen real estate. There was one place where I would have liked to have seen a comment explaining why something was done, but, of course, there weren’t any there.

I was surprised to see that the entire application was just one class. I’ve left the Kotlin code the same way because this is really an exercise in correcting issues, not in re-designing the application. This should help make it easier to compare the two versions. For this reason, I’ve left the structure of the class largely intact, which is why the menu code is way down at the bottom far away from all of the other layout code.

Overall Structure

In the Java code, all of the layout was performed in Application.start(), with method calls to configure particular elements. Generally speaking, the start() method should be about establishing the Stage and the Scene, and everything should be delegated. In this case, the layout was moved to createContent(), leaving just 3 lines in the start() method. Really, this is just application of SRP, but it does add to the readability:

override fun start(stage: Stage) {

stage.scene = Scene(createContent(), width, height)

stage.title = "Mandelbrot Set"

stage.show()

}

Having much more than this in your start() method is an anti-pattern.

The Layout

The Java code used Group as its base “layout” class!

Group group = new Group(canvas);

Scene scene = new Scene(group, width, height);

Group is basically a non-layout layout class. It puts the Nodes in it on the screen but, does nothing else to help position or configure them. I can count the number of times I’ve used Group over the past 10 years without even taking my mittens off (I’m in Canada). Group has its uses, but it shouldn’t be used this way.

In the Kotlin code, I used a BorderPane as the base layout. You can see how it works here:

The basic code looked like this:

private fun createContent() = BorderPane().apply {

top = mainMenuBar()

center = canvas

bottom = createBottom()

.

.

.

}

The createBottom() function looks like this:

private fun createBottom() = HBox(6.0).apply {

children += listOf(Label("Iterations: "),

iterationsBox(),

ProgressBar().apply {

progressProperty().bind(setProgress)

prefWidth = 200.0

},

Label(" Pending: "),

Label().boundLabel(Bindings.createStringBinding({ pendingSets.value.toString() }, pendingSets)),

Label(" Zoom:"),

Label().boundLabel(Bindings.createStringBinding({ zoom.value.roundToInt().toString() }, zoom)))

padding = Insets(6.0)

}

There’s now a lot more going on the bottom of the screen than there was before. We have a ProgressBar so that we can see how the rendering is going, an indicator for how many keystrokes & mouse clicks still need to be processed, and an indicator for how much we’ve zoomed in. There are two builders used, one for the TextField/Button combination, and one for the bound Labels.

I was tempted to write a builder for the ProgressBar, but I thought it wasn’t too disruptive leaving it in-line, and I thought it was instructive to show how you can do this stuff in Kotlin.

Let’s look at the builder for the iterations control:

fun iterationsBox() = HBox(6.0).apply {

val iterationsTextField = TextField()

val textFormatter: TextFormatter<Int> = TextFormatter(IntegerStringConverter())

iterationsTextField.textFormatter = textFormatter

val refreshButton = Button("Refresh").apply {

onAction = EventHandler {

canvas.requestFocus()

mandelbrotSet { maximumIterations = textFormatter.value?.toDouble() ?: 50.0 }

}

defaultButtonProperty().bind(iterationsTextField.focusedProperty())

}

children += listOf(iterationsTextField, refreshButton)

}

This uses TextFormatter with the standard JavaFX IntegerStringConverter to ensure that only whole numbers can be entered into the TextField, which is the right way to do this. Also note that all of the contents are local to the apply{} scope, and everything is self-contained, including the actions for the Button.

Now, contrast it with the original Java code:

public void textFieldIter(Group group, TextField typeIter, Button button) {

typeIter.setLayoutY(200);

button.setLayoutX(92);

button.setLayoutY(33);

button.setPrefWidth(78);

typeIter.setLayoutX(7);

typeIter.setLayoutY(33);

typeIter.setPrefWidth(78);

onlyNumbers(typeIter);

typeIter.setVisible(false);

button.setVisible(false);

group.getChildren().add(typeIter);

group.getChildren().add(button);

}

public void onlyNumbers(TextField text) {

text.textProperty().addListener((observable, oldNum, newNum) -> {

if (!newNum.matches("\\d*")) text.setText(newNum.replaceAll("[^\\d]", ""));

});

}

This doesn’t do anything with the action for the Button, either. That’s tucked away in the Menu code. Also note onlyNumbers(), which works, but isn’t the right way to go about this. The TextFormatter route also handles the conversion to Int as well. Imagine how much more code would be needed to add in a ProgressBar and 4 more Labels.

The Menus

The original Java code can only be described as a mess. It’s 150 lines of code with bad naming, repeated violations of DRY and an intense amount of coupling. Beginners seem to have particular difficulty with menus in JavaFX. On the upside, this code avoids using a dispatch event handler:

public void mainMenuBar(Stage stage, Group group, TextField typeHeight, TextField typeWidth, TextField typeIter, Button button1, Button button2) {

MenuBar menubar = new MenuBar();

menu1(menubar, group);

menu2(menubar);

menu3(stage, menubar, typeHeight, typeWidth, typeIter, button1, button2);

}

public void menu1(MenuBar menubar, Group group) {

Menu menu1 = new Menu("Color");

menubar.getMenus().add(menu1);

group.getChildren().add(menubar);

menubar.setPrefWidth(176);

CheckMenuItem m1i1 = new CheckMenuItem("Light");

CheckMenuItem m1i2 = new CheckMenuItem("Dark");

CheckMenuItem m1i3 = new CheckMenuItem("Colorful");

CheckMenuItem m1i4 = new CheckMenuItem("Solid White");

m1i1.setOnAction(e -> {

if (m1i1.isSelected()) {

colorLight();

m1i2.setSelected(false);

m1i3.setSelected(false);

m1i4.setSelected(false);

}

});

m1i2.setOnAction(e -> {

if (m1i2.isSelected()) {

colorDark();

m1i1.setSelected(false);

m1i3.setSelected(false);

m1i4.setSelected(false);

}

});

m1i3.setOnAction(e -> {

if (m1i3.isSelected()) {

colorHue();

m1i1.setSelected(false);

m1i2.setSelected(false);

m1i4.setSelected(false);As JavaFX code, this application had a lot of problems that are typical of programmers just starting out with

}

});

m1i4.setOnAction(e -> {

if (m1i4.isSelected()) {

colorWhite();

m1i1.setSelected(false);

m1i2.setSelected(false);

m1i3.setSelected(false);

}

});

m1i1.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("1"));

m1i2.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("2"));

m1i3.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("3"));

m1i4.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("4"));

menu1.getItems().addAll(m1i1, m1i2, m1i3, m1i4);

}

public void menu2(MenuBar menubar) {

Menu menu2 = new Menu("View");

menubar.getMenus().add(menu2);

MenuItem m2i1 = new MenuItem("Zoom in");

MenuItem m2i2 = new MenuItem("Zoom out");

MenuItem m2i3 = new MenuItem("Reset");

MenuItem m2i4 = new MenuItem("Move Up");

MenuItem m2i5 = new MenuItem("Move Down");

MenuItem m2i6 = new MenuItem("Move Left");

MenuItem m2i7 = new MenuItem("Move Right");

m2i1.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("Plus"));

m2i2.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("Minus"));

m2i3.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("Space"));

m2i4.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("UP"));

m2i5.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("DOWN"));

m2i6.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("LEFT"));

m2i7.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("RIGHT"));

m2i1.setOnAction(t -> zoomIn());

m2i2.setOnAction(t -> zoomOut());

m2i3.setOnAction(t -> reset());

m2i4.setOnAction(t -> up(100));

m2i5.setOnAction(t -> down(100)); //menubar location

m2i6.setOnAction(t -> left(100));

m2i7.setOnAction(t -> right(100));

menu2.getItems().addAll(m2i1, m2i2, m2i3, new SeparatorMenuItem(), m2i4, m2i5, m2i6, m2i7);

}

public void menu3(Stage stage, MenuBar menubar, TextField typeHeight, TextField typeWidth, TextField typeIter, Button button1, Button button2) {

Menu menu3 = new Menu("Image");

menubar.getMenus().add(menu3);

MenuItem m3i1 = new MenuItem("Set Iterations");

MenuItem m3i2 = new MenuItem("Save Image");

menu3.getItems().addAll(m3i1, m3i2);

m3i2.setOnAction(e -> {

typeHeight.setVisible(true);

typeWidth.setVisible(true);

button1.setVisible(true);

button2.setVisible(false);

typeIter.setVisible(false);

});

button1.setOnAction(e -> { //setting image resolution and saving

canvas.widthProperty().unbind();

canvas.heightProperty().unbind();

canvas.setWidth(Integer.parseInt(typeHeight.getText()));

canvas.setHeight(Integer.parseInt(typeWidth.getText()));

MandelbrotSet();

saveImage(stage, actualImage);

canvas.widthProperty().bind(stage.widthProperty());

canvas.heightProperty().bind(stage.heightProperty());

MandelbrotSet();

typeHeight.setVisible(false);

typeWidth.setVisible(false);

button1.setVisible(false);

});

m3i1.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("CTRL + C"));

m3i1.setOnAction(e -> {

typeIter.setVisible(true);

button2.setVisible(true);

typeHeight.setVisible(false);

typeWidth.setVisible(false);

button1.setVisible(false);

});

button2.setOnAction(e -> {

typeIter.setVisible(false);

button2.setVisible(false);

maximumIterations = Double.parseDouble(typeIter.getText());

MandelbrotSet();

});

m3i2.setAccelerator(KeyCombination.keyCombination("CTRL + V"));

}

I have to say this is the only place where I would have liked to see some comments, because I really couldn’t fathom why menu3 existed. All it seems to do is to hide and display the TextFields and Buttons. And why are the Button actions defined here?

It turns out that having those elements on the screen all of the time “steals” the keystrokes from the Scene that are used to zoom in and out, and to move the image around. Hiding them makes the keystroke controls work. I didn’t see that this was the problem until I’d refactored a lot of this, and ditched menu3 in the process. We’ll look at the keystroke controls in a bit.

A very big problem with this code is that all of the builder methods are void and they pass the containing class (MenuBar) down as a parameter. This introduces coupling. Also. the MenuItem names, like “m1i2”, are meaningless and couple back to the Menus. So if you removed a menu item, or added a new one, or changed the order, they’d all be misleading.

Finally, CheckMenuItem is the wrong class to use. JavaFX has a class called RadioMenuItem that ensures that handles all of the deselection of items automatically.

Let’s look at the Kotlin code:

private fun mainMenuBar() = MenuBar().apply {

prefWidth = 176.0

menus.addAll(menu1(), menu2())

}

@Suppress("UNCHECKED_CAST")

private fun menu1() = Menu("Color").also {

ToggleGroup().apply {

toggles += listOf(makeColourMenuItem("Light", "1") { mandelbrotSet { newSettings(246.0, maximumIterations, 0.9, 60, 0, 60) } },

makeColourMenuItem("Dark", "2") { mandelbrotSet { newSettings(0.0, 0.0, maximumIterations, 15, 15, 15) } },

makeColourMenuItem("Colourful", "3") { mandelbrotSet { newSettings(300.0, 1.0, 1.0, 35, 0, 35) } },

makeColourMenuItem("Solid White", "4") { mandelbrotSet { newSettings(0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0, 0, 0) } })

it.items += toggles as List<MenuItem>

}

}

private fun makeColourMenuItem(name: String, accel: String, func: () -> Unit) = RadioMenuItem(name).apply {

selectedProperty().addListener { ob: Observable -> if ((ob as ObservableBooleanValue).value) func.invoke() }

accelerator = KeyCombination.keyCombination(accel)

}

private fun menu2() = Menu("View").apply {

items += listOf(makeMenuItem("Zoom In", "Plus") { zoomIn() },

makeMenuItem("Zoom Out", "Minus") { zoomOut() },

makeMenuItem("Reset", "Space") { reset() },

makeMenuItem("Move Up", "UP") { up(100) },

makeMenuItem("Move Down", "DOWN") { down(100) },

makeMenuItem("Move Left", "LEFT") { left(100) },

makeMenuItem("Move Right", "RIGHT") { right(100) })

}

private fun makeMenuItem(name: String, accel: String, eventHandler: EventHandler<ActionEvent>) = MenuItem(name).apply {

accelerator = KeyCombination.keyCombination(accel)

onAction = eventHandler

}

Here we only have 35 lines of code, and it’s a lot easier to read. Firstly, DRY has been followed by creating builder methods for the two kinds of MenuItems. Now we have no repeated code.

The RadioMenuItems need to be placed into a ToggleGroup so that they’ll automatically deselect.

Changing Settings

It bears looking at the newSettings method. Originally, we had this:

public void colorLight() {

hue = 246.0;

saturation = maximumIterations;

brightness = 0.9;

R = 60;

G = 0;

B = 60;

MandelbrotSet();

}

public void colorDark() {

hue = 0;

saturation = 0;

brightness = maximumIterations;

R = 15;

G = 15;

B = 15;

MandelbrotSet();

}

public void colorHue() {

hue = 300.0;

saturation = 1.0;

brightness = 1.0;

R = 35;

G = 0;

B = 35;

MandelbrotSet();

}

public void colorWhite() {

hue = 0.0;

saturation = 0.0;

brightness = 1.0;

R = 0;

G = 0;

B = 0;

MandelbrotSet();

}

Is this a violation of DRY???

It’s not really duplicated code, is it? Some lines are duplicated in some of the methods, and the call to MandelbrotSet() is duplicated in each one.

But you can paramaterize the values, and have a single method that does the work:

private fun colorLight() {

mandelbrotSet { newSettings(246.0, maximumIterations, 0.9, 60, 0, 60) }

}

private fun colorDark() {

mandelbrotSet { newSettings(0.0, 0.0, maximumIterations, 15, 15, 15) }

}

private fun colorHue() {

mandelbrotSet { newSettings(300.0, 1.0, 1.0, 35, 0, 35) }

}

private fun colorWhite() {

mandelbrotSet { newSettings(0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0, 0, 0) }

}

private fun newSettings(newHue: Double, newSat: Double, newBright: Double, newRed: Int, newGreen: Int, newBlue: Int) {

hue = newHue

saturation = newSat

brightness = newBright

red = newRed

green = newGreen

blue = newBlue

}

This felt like an improvement.

However, I now had 4 one-line methods that were each called from one place. Ordinarily, methods like that serve one purpose: The name of the method tells us what that single line of code does.

In this case, the methods were called from MenuItem builders that already had the MenuItem name in them. So it was clear what they did. So I refactored out these methods, and just put them in-line in the builder call for the MenuItems.

Changing Settings

All over the application there was code like this:

public void zoomIn() {

zoom /= 0.7;

MandelbrotSet();

}

Some sort of change to a global control variable, and then a call to MandelbrotSet() to re-render the image. This two-step approach, repeated all over the place just felt wrong.

I changed the signature of MandelbrotSet() such that it accepted a Runnable (actually the Kotlin equivalent), and then MandelbrotSet() would be responsible for running it. So these calls then changed to things like:

private fun zoomIn() {

mandelbrotSet { zoom.value /= 0.4 }

}

In Kotlin, you can drop the “()” when the only parameter is a lambda.

In the case of zoomIn(), it was called from a couple of places, so it stayed as a function. A few others were refactored out. However, since the main purpose of this was to be passed around as a parameter, it made more sense to instantiate them as variables:

private val zoomIn: () -> Unit = { mandelbrotSet { zoom.value /= 0.4 } }

private val zoomOut: () -> Unit = { mandelbrotSet { zoom.value *= 0.4 } }

private val up: (Int) -> Unit = { mandelbrotSet { yPos -= height / zoom.value * it } }

private val down: (Int) -> Unit = { mandelbrotSet { yPos += height / zoom.value * it } }

private val left: (Int) -> Unit = { mandelbrotSet { xPos -= width / zoom.value * it } }

private val right: (Int) -> Unit = { mandelbrotSet { xPos += width / zoom.value * it } }

private val reset: () -> Unit = {

mandelbrotSet {

zoom.value = 250.0

xPos = -470.0

yPos = 30.0

}

}

This is both more concise and more “Kotlin-like” in my opinion.

While this gives more concise code, the big functional difference here is that MandelbrotSet() is now executing the parameter change control. This turns out to be a very important factor when moving the rendering to a background thread and handling multiple clicks and keypresses…

The Rendering Routine

Let’s look at the core of the processing first:

private fun iterationChecker(cr: Double, ci: Double): Int {

var iterationsOfZ = 0

var zr = 0.0

var zi = 0.0

while (iterationsOfZ < maximumIterations && ((zr.pow(2) + zi.pow(2)) < 4)) {

val oldZr = zr

zr = zr * zr - zi * zi + cr

zi = 2 * (oldZr * zi) + ci

iterationsOfZ++

}

return iterationsOfZ

}

private fun performMandelbrot(progressConsumer: (workDone: Long, maxWork: Long) -> Unit) = WritableImage(canvas.width.toInt(), canvas.height.toInt()).apply {

println("Starting mandelbrot")

val centerY = width / 2.0

val centerX = height / 2.0

val counter = AtomicLong(0)

(0 until width.roundToInt()).toList().parallelStream().forEach { x ->

progressConsumer.invoke(counter.incrementAndGet(), width.roundToLong())

for (y: Int in 0 until height.roundToInt()) {

val cr = xPos / width + (x - centerY) / zoom.value

val ci = yPos / height + (y - centerX) / zoom.value

pixelWriter.setColor(x, y, determineColour(iterationChecker(cr, ci)))

}

}

println("Done")

}

private fun determineColour(iterations: Int): Color {

if (iterations.toDouble() == maximumIterations) { //inside the set

return Color.rgb(red, green, blue)

}

if (brightness == 0.9) { //white background

return Color.hsb(hue, iterations / maximumIterations, brightness)

}

if (hue == 300.0) { //colorful background

return Color.hsb(hue * iterations / maximumIterations, saturation, brightness)

}

if (hue == 0.0 && saturation == 0.0 && brightness == 1.0) {

return Color.hsb(hue, saturation, brightness)

}

return Color.hsb(hue, saturation, iterations / brightness)

}

Really, only a few things have been changed here.

- The name was changed

MandelbrotSet()has been changed toperformMandelBrot(). ThemandelbrotSet()now controls theTasksetup. This method now returns aWritableImage.- Colour determination was moved to

determinColour - The Intellij Idea conversion to Kotlin did a horrible job on the loops, converting the

for()loops into manual loops. This made the whole thing kind of confused. It helped to move this code out of the loop, and helped with DRY. - Parallel Processing was introduced

- The

for()loop forxwas replaced with aparallelStream()over a list ofxvalues.

The new mandelbrotSet() method looks like this:

private var taskRunning = false

private val preProcesses = mutableListOf<() -> Unit>()

private val pendingSets: IntegerProperty = SimpleIntegerProperty(0)

private fun mandelbrotSet(preProcessor: () -> Unit = {}) {

if ((canvas.width > 0) && (canvas.height > 0)) {

preProcesses += preProcessor

pendingSets.value = preProcesses.size

if (!taskRunning) {

taskRunning = true

preProcesses.forEach { it.invoke() }

preProcesses.clear()

pendingSets.value = 0

val task = object : Task<WritableImage>() {

override fun call(): WritableImage = performMandelbrot { workDone, maxWork -> updateProgress(workDone, maxWork) }

}

task.setOnSucceeded {

canvas.graphicsContext2D.drawImage(task.value, 0.0, 0.0)

taskRunning = false

if (preProcesses.isNotEmpty()) {

mandelbrotSet()

}

}

setProgress.unbind()

setProgress.bind(task.progressProperty())

Thread(task).start()

}

}

}

This method is responsible for controlling what runs on the FXAT, and what runs on a background thread. Everything in here except for:

override fun call(): WritableImage = performMandelbrot { workDone, maxWork -> updateProgress(workDone, maxWork) }

runs in the FXAT.

It turns out that weird things happen if the global parameters change while the rendering is running, so this has to be defended against. Also, we don’t want multiple Tasks running at the same time. It’s also true that we can run several parameter changes before running the rendering engine again. This means that we can save up the changes, run them in a batch and the run the renderer. And that’s what we do.

The flow is straight-forward. Add the new parameter change into the batch of changes pending, and then check to see if a Task is running. If it is, then you’re done.

If no Task is running, then stream through the pending parameter changes, running each one and then clear the list. Launch a Task to run the renderer.

When the Task is complete, then push the WritableImage from the Task onto the canvas. If any new parameter changes have come in while the Task was running, then the change list will be non-empty. In this case, just call the routine again.

Remember that the FXAT is single-threaded, and any actions from clicks and keystrokes are going to be put into the event queue and won’t be handled until after any other jobs are run on the FXAT. So it’s impossible for the pending change list to change list to change while any of this code is running on the FXAT. This means that this approach is pretty much fool-proof.

All of this works because of the earlier refactoring that passed responsibility for the parameter changes to mandelbrotSet().

About the Stolen Keystrokes…

The reason for that has been covered in my article about Events. In a nutshell, in any given scene something is going to have “focus”. It will end up being the “source” for keystroke Events. However, all Events get passed through a chain of Nodes starting at the Scene, and then working down through the various layout containers that hold the source Node. Every one of those layout containers gets a first chance to handle the Event before it’s passed on to the next level down. And they all have a chance to stop the Event from being passed down. This is called, “consuming” the Event.

This process of going down the chain is called the “Event Capturing Phase”, and controlled by installing EventFilters on the container Nodes.

For this case, we add the following EventFilter to the main BorderPane.

addEventFilter(KeyEvent.KEY_PRESSED) {

if (processKeystroke(it.code, it.isShiftDown)) {

it.consume()

}

}

And here’s the code for processKeystroke():

private fun processKeystroke(keyCode: KeyCode, isShiftDown: Boolean): Boolean {

var didSomething = true

when (keyCode) {

KeyCode.W, KeyCode.UP -> up(if (isShiftDown) 10 else 100)

KeyCode.A, KeyCode.LEFT -> left(if (isShiftDown) 10 else 100)

KeyCode.S, KeyCode.DOWN -> down(if (isShiftDown) 10 else 100)

KeyCode.D, KeyCode.RIGHT -> right(if (isShiftDown) 10 else 100)

KeyCode.EQUALS -> zoomIn()

KeyCode.MINUS -> zoomOut()

KeyCode.SPACE -> reset()

KeyCode.ESCAPE -> Platform.exit()

else -> {

didSomething = false

}

}

return didSomething

}

Since processKeystroke() only recognizes certain keystrokes, it returns a Boolean to indicate whether or not it did anything. Then we use that return value to decide if we should consume the Event. For the most part, the navigation keystrokes aren’t really used inside a TextField, so the two uses of keystrokes are fairly mutually exclusive. This approach works good enough.

Conclusion

Beginners seem to be taught only how to create code that runs, with little consideration for the quality of the code in respect to readability and maintance. But these are critical factors, even when the application is still in development. This project is a case in point, the actual problem was made much more difficult to solve because the entire code was much more complicated than it needed to be.

I don’t think you need to read through all the code in detail and understand what every lines does in both versions to appreciate the process of cleaning up the code and making it easier to deal with. I’ve tried to explain the reasoning behind the changes as much as I can, so that you can decide if you agree with it or not.