What You’ll Learn

- The importance of using background threads.

- How to use Task to process on a background thread.

- Considerations for the GUI while a background task is running.

- Avoiding concurrency issues when multi-threading

- Avoiding Button double-clicks.

The Problem With Our Application

Virtually any database or external API you call from your application has at least the potential to take a measurable amount of time to respond, or to possibly time out and not return an answer at all.

What happens is that your Java code eventually needs to hand off to some other process to do the work. Maybe you’ve executed an HTTP “Get” command, or you’ve asked the kernel to read a file, or you’ve invoked an API handler for an application running on your computer. In all of these cases, your Java code is going to invoke an external process and then execute a wait() statement, or at least its equivalent. When the external process completes, it will send a signal to your Java process to wake up and continue on.

The problem that this presents for JavaFX is that it’s always busy. It’s always checking for mouse movements, events that are triggered, button clicks, data changes that impact the GUI. It’s always busy and it all happens on a single thread - the “FX Application Thread” or “FXAT”. This includes the code that you write that works as an EventHandler - it all runs on the FXAT by default (as it should).

The one thing you should NEVER do is execute a wait() (or its equivalent) on the FXAT. When you do this, everything in your GUI - EVERYTHING - stops dead. As a matter of fact, you should never execute anything on the FXAT that takes more than a few milliseconds to run.

Right now, our database is an inaccurate simulation because it has no latency. Let’s fix that…

Adding Latency to Our Database

The easiest way to add latency is to simple put a Thread.sleep() command in our database method. Like this:

public class CustomerDatabase {

private Map<Integer, Map<String, String>> data = new HashMap<>();

private Integer nextKey = 0;

public int saveCustomer(Map<String, String> customerRecord) {

try {

Thread.sleep(10000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

customerRecord.put("_id", (++nextKey).toString());

data.put(nextKey, customerRecord);

return nextKey;

}

Map<Integer, Map<String,String>> getData() {

return data;

}

}

If you run this now, you’ll see that the GUI goes entirely inactive for 10 seconds. Nothing happens when you click on a TextField, click the button or try to expand the window. I’d show you, but there’s simply nothing to see. It’s just…dead.

There’s a problem with this approach, though. Our tests now take forever to run. Let’s look at the console output from running the database tests:

> Configure project :

Project : => 'ca.pragmaticcoding.beginners' Java module

> Task :compileJava UP-TO-DATE

> Task :processResources UP-TO-DATE

> Task :classes UP-TO-DATE

> Task :mergeClasses SKIPPED

> Task :compileTestJava

> Task :processTestResources NO-SOURCE

> Task :testClasses

> Task :test

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 52s

4 actionable tasks: 2 executed, 2 up-to-date

11:36:56 a.m.: Execution finished ':test --tests "ca.pragmaticcoding.beginners.part8.CustomerDatabaseTest"'.

52 seconds!

This is not acceptable. Unit tests should never take more than a few milliseconds to run each. This is one of the reasons that you never access live databases from unit tests.

We need to find a way to add the latency to the application without slowing down our tests.

One way to do this is to implement the sleep() in a separate class extended from our database class. Then we can continue to test the original database class, while using a “slow” version for our production code:

public class SlowCustomerDatabase extends CustomerDatabase {

private final int delay;

public SlowCustomerDatabase(int delay) {

this.delay = delay;

}

@Override

public int saveCustomer(Map<String, String> customerRecord) {

delay();

return super.saveCustomer(customerRecord);

}

private void delay() {

try {

Thread.sleep(delay);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

}

}

Then we’ll modify CustomerDao to use our “slow” version for the production code:

public class CustomerDAO {

static CustomerDatabase database = new SlowCustomerDatabase(5000);

public int saveCustomer(Map<String, String> customerRecord) {

return database.saveCustomer(customerRecord);

}

}

Now our production code runs with a delay, and our test code completes in less than 1 second.

I’ll admit that this is a bit of a cheat. In a real world example you don’t have the luxury of simulating a database without latency for your automated testing. But in the real world, you never run automated tests against an actual database. What you would have to do is create Mocking classes for the database connections that can respond instantly and in exactly the way that you want - every time. But that is way beyond the scope of this tuturial.

The Solution: A Background Thread

Now, if our database has latency and blocks, meaning that we can’t access it on the FXAT, then the correct solution is to do the access on some other thread. This is usually referred to as a “background thread”, because it runs in the background while the FXAT keeps doing its thing.

JavaFX has a tool just for doing this. It’s called Task. So that’s what we’re going to use.

In MVCI, the Controller is responsible for controlling threads. So that’s where we are going to implement our Task:

public class CustomerController {

private final Builder<Region> viewBuilder;

private final CustomerInteractor interactor;

public CustomerController() {

CustomerModel model = new CustomerModel();

interactor = new CustomerInteractor(model);

viewBuilder = new CustomerViewBuilder(model,this::saveCustomer);

}

private void saveCustomer() {

Task<Void> saveTask = new Task<>() {

@Override

protected Void call() {

interactor.saveCustomer();

return null;

}

};

Thread saveThread = new Thread(saveTask);

saveThread.start();

}

public Region getView() {

return viewBuilder.build();

}

}

Some Information About Task

Task is a utility class that is designed to run some code in a background thread. Task itself is abstract, and has 1 abstract method: call(). The most common way to use Task is to instantiate an anonymous inner class that extends Task and supply the implementation of call(). That’s what we’ve done in this example. Task extends classes that implement Runnable, so that when we supply it to a Thread in it’s constructor and then invoke Thread.start() it will invoke Task.call() in that Thread.

This means that any code that we put into Task.call() will be run on a background thread.

When you start dealing with threads, you need to wrap your mind around the idea that pieces of your code will run simultanously, and you can no longer expect your code to run in a linear fashion. The code that instantiates the Task, defines Task.call() and starts the Task running on a background thread all runs on the FXAT. Whatever code that comes after Thread.start() will happen immediately, and will not depend on the completion of Task.call(). You cannot wait for it on the FXAT, because then your GUI would freeze.

In our example, saveThread.start() is the last line of code in CustomerController.saveCustomer() and is probably the last line of code in the job that the FXAT is running when it executes it. So the FXAT is going to going to go on and handle the next job in its queue.

You may also notice that Task is generic, and that Task.call() returns a value of whatever type we declare our instance of Task as. In our case, we don’t have a value to return, and so we are just using Void.

Back to Our Example

Really, at this point, all we’ve done is take the call to CustomerInteractor.saveCustomer() and run it in another thread. We don’t need Task to do that, do we?

Let’s take a look at what happens when this runs. There’s nothing much to see, but the GUI isn’t dead any more. I can interact with it while I’m waiting for the database call to complete, and it works.

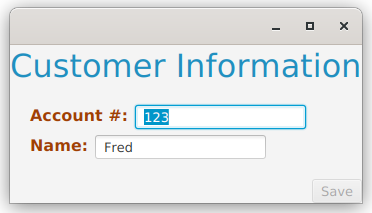

But there’s a problem. Here’s what I did:

- Entered account, “123” and name “Fred”

- Clicked “Save”

- Clicked “Save” again.

- Went back to the name TextField and added “ Smith”

- Clicked “Save” again.

- Clicked “Save” again.

Here’s the console output:

> Task :run

Saving account: 123 Name: Fred S Result: 1

Saving account: 123 Name: Fred Smith Result: 2

Saving account: 123 Name: Fred Smith Result: 3

Saving account: 123 Name: Fred Smith Result: 4

Oh, oh! There’s no save for just “Fred”! The first save is for “Fred S”. At no point did I click when the name TextField said just “Fred S”. What’s going on here?

It turns out the reason for this is in the Interactor:

public void saveCustomer() {

int result = broker.saveCustomer(createCustomerFromModel());

System.out.println("Saving account: " + model.getAccountNumber() + " Name: " + model.getCustomerName() + " Result: " + result);

}

We call the Broker, which calls the DAO which calls the “slow” database which returns a results after 5 seconds. Then we output some information to the console which combines the return value from database with data from the Model. But the Model is now shared between two threads, the FXAT and our background thread. And when we click over and over, it’s shared by even more threads.

This can be a problem.

Since changes to the GUI are “live” changes to State, whenever we need to use State in a background thread we need to do one of two things:

- Copy the elements of State to some place private to the background thread.

- Lock the GUI so that it cannot update State.

Let’s do the first here (this code is in the Interactor):

public void saveCustomer() {

String customerName = model.getCustomerName();

String account = model.getAccountNumber();

int result = broker.saveCustomer(createCustomerFromModel());

System.out.println("Saving account: " + account + " Name: " + customerName + " Result: " + result);

}

That’s an improvement. Now when I enter “123” and “Fred”, click “Save” and then change the name to “Fred Smith”, then click save two more times I get:

> Task :run

Saving account: 123 Name: Fred Result: 1

Saving account: 123 Name: Fred Smith Result: 2

Saving account: 123 Name: Fred Smith Result: 3

That’s way better. It’s probably a safe bet that the background thread is going to launch and the broker call is going to start executing before anyone could ever get their hand off the mouse and start typing into any of the TextFields. That being said, this is something that you might want to look out for in a real application.

But it’s still disturbing that you could click on that Button three times before it finished processing. That’s something that we should deal with.

More About Task - Completion Events

You may have been wondering, “Why bother with Task? Why not put a Runnable in a Thread?”.

Task is specifically designed to allow you to co-ordinate code on the FXAT with background code, which is a crucial ability. One of the ways that it does this is with a set of Events that are fired when the background job ends. These are defined in the Task as ObjectProperty<EventHandler> and you can put EventHandlers in them.

There are three ways that a Task can end:

- Completed

- This is fired when the code in

Task.call()completes normally. - Failed

- This happens only when the code in

Task.call()terminates with an uncaught, unhandledExceptionof any type. - Cancelled

- This fires when some code calls

Task.cancel(). If you don’t have any code that does this, then you don’t have to worry about it.

You can set up these event handlers by calling Task.setOnCompleted(), Task.setOnFailed() or Task.setOnCancelled().

The key idea behind this is that all EventHandlers run on the FXAT! This means that you can write some code, in an EventHandler, that will be executed on the FXAT when the Task completes its job. This turns out to be very, very powerful…

Back to Our Example (Again)

One of the ways that you can utilize this power is to create a “workflow” for creating and running a Task. Generally, that workflow is something like this:

- [FXAT] Put the GUI in the state that you want it while the

Taskruns. - [Background] Execute the

Task. - [FXAT] Put the GUI back into its “normal” state when the

Taskcompletes.

The first and last steps are performed on the FXAT, the Task executes on the background thread.

There’s just one problem, though. The GUI stuff is the property of the View, and the Task is part of the Controller. How do you handle this?

The first thing we’re going to do is change our saveHandler from a Runnable to a Consumer<Runnable>. Then we’re going to have our Controller execute that Runnable passed through the Consumer in the Task completion EventHandler. It’s more complicated to explain than it is to just see the code:

private void saveCustomer(Runnable postTaskGuiActions) {

Task<Void> saveTask = new Task<>() {

@Override

protected Void call() {

interactor.saveCustomer();

return null;

}

};

saveTask.setOnSucceeded(evt -> postTaskGuiActions.run());

Thread saveThread = new Thread(saveTask);

saveThread.start();

}

Now saveCustomer() is passed a Runnable, which it runs when the Task completes.

What happens in the View is a little bit more interesting, first the constructor:

public CustomerViewBuilder(CustomerModel model, Consumer<Runnable> saveHandler) {

this.model = model;

this.saveHandler = saveHandler;

}

You can see here that we’ve changed the type of saveHandler from a Runnable to a Consumer<Runnable>. Let’s take a look at that a little closer. A Consumer is a “Functional Interface” that accepts a single parameter and returns nothing. It “consumes” the value that it is passed. In this case, it will be consuming a Runnable, which is just a snippet of executable code.

Remember that this saveHandler is passed in to the View. The View isn’t going to define it, it is going to invoke it. But the View is going to define the Runnable that it passes to saveHandler.

Let’s look at how that works in the code for the Button:

private Node createButtons() {

Button saveButton = new Button("Save");

saveButton.setOnAction(evt -> {

saveButton.setDisable(true);

saveHandler.accept(() -> saveButton.setDisable(false));

});

HBox results = new HBox(10, saveButton);

results.setAlignment(Pos.CENTER_RIGHT);

return results;

}

The Runnable that is passed to saveHandler is the single command, saveButton.setDisable(false). This is passed to the Consumer via Consumer.accept(), and is the code that is then passed back to the Controller as a Runnable and then gets put into the onCompleted EventHandler of the Task. So it’s actually passed around twice.

Now, when the Button is clicked, the first thing that happens is that it is disabled. Then the saveHandler is invoked, passing it a Runnable that re-enables the Button. Like this:

The Button will remain disabled until the Task completes, and the onCompleted EventHandler is executed. That EventHandler will call Runnable.run() which will execute saveButton.setDisable(false) and the Button will be re-enabled.

In this way, we keep the GUI code in the ViewBuilder, and the control over the threading in the Controller.

Keeping Secrets

Let’s look at what the elements of our MVCI framework “know”, and “don’t know” about each other.

-

The Controller knows that it needs to supply the View with a Consumer that it can call to pass back a

Runnablethat is associated with the completion saving a customer record. Invocation of thisConsumershould trigger the customer record save. -

The Controller has no knowledge of what that

Runnabledoes. -

The Controller has no knowledge of how the

Consumerwill be invoked. -

The View knows that it will get a

Consumerfrom whatever class instantiates it. It knows that thisConsumeris related to saving a customer and needs to be invoked (viaConsumer.accept()) to execute the save. -

The View does not know what the

Consumerdoes. -

The View does not know how the

Runnablethat it supplies will be invoked. -

The Controller knows that it has to call

Interactor.saveCustomer()via aTaskin response to invocation of theConsumerby the View. -

The Controller has no knowledge of what

Interactor.saveCustomer()does. -

The Interactor has no knowledge of any external components except the Model.

-

The Interactor is NOT aware that

saveCustomer()will be run on a background thread.

This last item is a bit fluid. There may be occasions when an Interactor method is designed to run on either the FXAT or a background thread and you’ll need to keep away from doing certain things in either case.

Conclusion

Connecting your application to the real world means that you have to cope with blocking API calls, and that means you have to use background threads to handle these connections. But multi-threading means concurrency and concurrency brings its own issues. This is unavoidable, as the GUI needs to remain active while external access is running, and just something you’ll need to learn how to handle.

Programmers are used to imperative programming, where programs execute in a linear fashion and you always know how you got somewhere and the state of your application when you get there. Reactive programming breaks this paradigm, and multi-threaded programming complicates it even more. It’s not really difficult to cope with, but it takes some time to get used to the new way of thinking.