Designing a Game

Everyone always wants to start at the UI. After all, it’s a visual game, no?

But that’s not right. If you can’t visualize how the game works as data and logic, then having a UI created without that understanding just puts you way, way backwards.

So the first thing is to think about how the game works as data.

How I Would Think About It

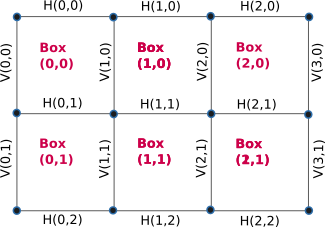

OK, so yes we need to look at the game visually, but just to translate it into data. Here’s an example of the game layout, with some labels to link to data:

Now you have horizontal lines and vertical lines. And, to start with, we’ll track them separately.

The important thing to note is that Box(0,0) is bounded by H(0,0), H(0,1), V(0,0) and V(1,0). And Box(1,1) is bounded by H(1,1), H(1,2), V(1,1) and V(2,1).

So we can generalize from this that Box(x,y) is bounded by:

- H(x,y)

- H(x,y+1)

- V(x,y)

- V(x+1,y)

Now we have a dependency relationship between the lines and the boxes!

We’re done with the visuals for now. We got what we needed out of it.

Game Mechanics

Now we have two object types GameLine (let’s call them that since JavaFX has it’s own class called Line that we’ll probably need to use), and Box.

There’s really one thing about a GameLine that is important: if it’s been “activated”. That’s it.

For a Box there are two things that are important: If all of the lines associated with it have been activated - then it’s “completed”, and which player completed it.

It’s really tempting to do something like this because the GameLine only has a single Boolean attribute:

private Boolean[][] horizontalLines = new Boolean[4][4];

private Boolean[][] verticalLines = new Boolean[4][4];

But that would probably be a mistake. First off, it’s not very Java because it’s not very Object Oriented. Secondly, the knowledge about the GameLine is split between the array itself (which holds its location) and the value in the array.

Better would be to create an object, GameLine and give it these fields:

- Column

- Row

- Type (Horizontal or Vertical) (Make this an Enum called

LineType) - Activated? (Boolean)

This is so much better because it’s now an autonomous entity. Everything about it is encapsulated within it, and you don’t need to depend on whatever data structure it’s stored in to find out what kind of line it is, or where it’s located.

Once you’ve done this, you can ditch the arrays completely since the GameLines themselves know where and what they are. So you can just put them in a List:

private List<GameLine> gameLines = new ArrayList<>();

You can find a line by iterating through the gameLines until you get one with the correct row, column and type.

Now you’re probably thinking, “Ooooh, yuk! That’s so much less efficient than just going line = horizontalLines[37][54].”.

Maybe so, but…

I had a boss years ago that said this to me when I was scratching my head trying to make something more efficient for no reason: “What do you care if the computer has to work harder? It’s not going to get tired.” GameLine findOrCreateGameLine(LineType type, int column, int row) { for (GameLine line : gameLines) { if ((line.type.equals(type)) && (line.column == column) && (line.row == row)) { return line; } } GameLine newLine = new GameLine(column, row, type); gameLines.add(newLine); return newLine; } That’s so true. Even if your game board was 1000x1000 dots, it’s gonna take a loop about 0.000001s to find a line in an array. It’s totally inconsequential. It’s definitely going to be too fast for a user to detect a delay. So forget about it.

It’s way more important to design your application so that it’s easier to understand, and messing around with multi-dimensional arrays always gets more complicated that you need it to be.

Moving on…

Boxes have the following fields:

- Column

- Row

- List of GameLines around it.

- Completed? (Boolean)

- Owner (player 1 or 2, or none) (Make this an Enum called

BoxOwnerorPlayer)

Same deal as with the GameLines, just use a list:

private List<Box> boxes = new ArrayList<>();

Populating The Board Data

Here’s the key: Treat that List of GameLines like a cache.

What does that mean?

Write a method like this:

GameLine findOrCreateGameLine(LineType type, int column, int row) {

gameLines.forEeach(gameLine -> {

if ((gameLine.type == type) && (gameLine.column == column) && (gameLine.row == row)) {

return gameLine;

}

})

// You can only get here if nothing matched

GameLine gameLine = new GameLine(type, column, row);

gameLines.add(gameLine);

return gameLine;

}

This means that a GameLine doesn’t exist until you go looking for it the first time, in which case it creates it and puts it into the cache. After that, it’ll just be pulled out of the cache when it’s needed.

The awesomeness of this is that you never have to do the nested loop stuff to create the lines!

Think about populating the game board from the perspective of Boxes instead of lines. This is the only place that you’ll have nest loops for column and row. It’ll look something like this:

void populateBoard(int maxColumns, int maxRows) {

for (int column = 0; column < maxColumns; column++) {

for (int row = 0; row < maxRows; row++) {

GameLine topLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.HORZ, column, row);

GameLine bottomLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.HORZ, column, row+1);

GameLine leftLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.VERT, column, row);

GameLine rightLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.VERT, column+1, row);

boxs.add(new Box(column, row, topLine, bottomLine, leftLine, rightLine));

}

}

}

Obviously, the constructor for Box will have to initalize a list of GameLines and populate it.

Playing the Game

The only other piece of data that you need is some place to hold the active player. Let’s call it activePlayer.

Now you can conceptualize the actual game play. Create a method called activateLine(LineType type, int column, int row). This is what it does:

- Loop through

boxesand count the number of completedBoxes, save this asstartingCompleted(or something like that). - Call

findOrCreateGameLine(type, column, row)and set itsactivatedfield to true. - Loop through the

Boxesand do the following:- If the

Boxis completed, skip it. - Loop through its list of

GameLines, and check to see if they are all activated. If not, then go to the nextBox. - Set the

Boxcompletedtotrue. - Ste the

Boxownerto the current player.

- If the

- Loop through

boxesand count the number of completedBoxes. - If the number of completed

Boxesis greater than at the beginning, then stop. - Flip the

activePlayer

Testing it

You can now write a testing method called playGame(). Set up the starting stuff, call populateBoard() and then call activateLine() over and over simulating the moves. All without a GUI. At the end, you should be able to count up the owners of all of the boxes and get the right answer.

You could run a simulation like the way this one runs:

If you can do that, then you can start to think about a GUI would interact with your gameplay. The cool thing is that, if you do it right, almost none of the code you right to work without a GUI is going to get thrown away.

Some Notes about Fields and Constructors

When you declare a field in a class you can specify a number of things:

- The type of the data.

- The visibility of the data.

- The initial value of the data.

- Whether or not the data can be changed.

So you can do something like this:

private String fred = "I am fred";

private final String george;

public final String MARVIN = "I am Marvin";

In this example, fred is just a regular variable, it’s been initialized to “I am fred”, but can be changed at any time. MARVIN is essentially a constant. It’s final, so it can’t be changed and it has the value “I am Marvin”.

Now, george is a bit strange. It’s final, but it has no value! What’s going on here?

First, when I started out I never used final at all. Why bother? Then I’ve come to understand that it’s really important. When you’re programming you really need to program exactly what you intend. If something shouldn’t be changed, then program it that way. Don’t rely on the fact that you know not to change it, or that there won’t be any code that changes it. If the nature of something is that it shouldn’t be changed, if you intend to never change it, then code it that way with final.

Back to george. Since george isn’t initialized in the declaration, yet it’s final. This means that it has to be initialized in a constructor.

A constructor is the code that’s run when new is performed on a class to construct an object. You can have multiple constructors if there are multiple ways that you might want to create an object of a particular class. Those constructors can only differ in the parameters that they take.

So:

public class Blah {

private final String fred;

public Blah() {

fred = "I am fred";

}

public Blah(String fredsName) {

fred = fredsName;

}

}

Now let’s think about GameBox. It has the following fields:

- int

column - int

row - List

`sides` - boolean

completed - BoxOwner

owner

Of these, column, row and sides should all be set only when the GameBox is created. Which means that they should all be final. Clearly, we don’t know what the values are when we write the class, so this means that they need to be set in the constructor, and they need to be passed to the construct from whatever code calls it. This makes sense, no?

The fields, completed and owner both have initial values that we know right now (false, and NONE). So they should be set in the declaration. No need to deal with them in the constructor.

Let’s think about sides. It’s a List, so the idea of final gets a little confusing. Let’s look at it this way: For any given instance of GameBox, there is only ever going to be one List of sides. You’re never going to wipe it out and replace it with a new List. So the list itself needs to be final.

But in Java, there’s no immutable list (there is in Kotlin, which is really cool, but not Java). That means that you’ll always be able to add or remove elements of the List, no matter what you do. So let’s ignore that for now.

But as a container, you really should initialize it in the declaration, but we have to leave it empty until the constructor because we don’t know what the sides are until the constructor is called. So the declaration of sides should look like this:

private List<GameLine> sides = new ArrayList<>();

Then when you get the sides passed to constructor you can do something like:

sides.addAll(top, bottom, left, right);

Finally, let’s think about scope. Generally speaking, fields should always be private in a class. The idea is that the inner structure of a class is nobody else’s business. This way, if you want to change the structure of a class, it can’t impact any other part of your application because they can’t reference it.

This is important with what we are doing. You’ll see this when we go back to looking at the UI

In order to allow other classes to read or update fields, we create methods called getters and setters. Once you write a getter or a setter, you can’t change its return type or its parameters because it’s public and that would mean that you have to change other classes because you’ve broken them. That’s pretty much the point of getters and setters.

Here’s the neat thing: You can’t have a setter for a final field. Because you can’t update it. So the whole concept ties together.

The other thing is that you don’t just write getters for every field. You need to think about how the fields are going to be used, and who should be doing that work.

Let’s look at column and row. Do any other classes need to know the column and row of a GameBox?

Potentially, we have the idea of looking for a particular GameBox by its coordinates. Something like this:

gameBoxes.forEach(gameBox -> {

if ((gameBox.getColumn() == column) && (gameBox.getRow() == row)) {

return gameBox;

}

});

But is that really the best way to do this? Who should be responsible for deciding a GameBox is at a particular location? Probably GameBox itself. So what you should do, rather than create getters for column and row, is to create a method that says “yes” or “no” to a particular location:

public class GameBox {

.

.

.

public boolean isAtLocation(int column, int row) {

return ((this.column == column) && (this.row == row));

}

}

Now your for loop looks like this:

gameBoxes.forEach(gameBox -> {

if (gameBox.isAtLocation(column,row) {

return gameBox;

}

});

But hang on. Do we ever need to find a GameBox by location for our game mechanics? I can’t think of any reason. Do we use column and row anywhere inside GameBox? I don’t think so.

There’s a really important concept called “YAGNI” (You Ain’t Gonna Need It) in programming. Don’t write stuff that you think that you “might need” some time in the future. Because, very often, you’re not going to need it. And if you do, you’ll need it in different way than you thought. And in the meantime, that stuff you don’t need is sitting in your code and occupying space in your head every time you look at it.

So, let’s get rid of column and row from GameBox. Because YAGNI. Just delete the field declarations, and don’t pass them to the constructor.

Now the field list for GameBox looks like this:

- List

`sides` - boolean

completed - BoxOwner

owner

And the constructor call would be new GameBox(top, bottom, left, right).

One last thing to note: Remember, our only game play action is activateLine(type, column, row), which then triggers a whole bunch of logic. The most important parts are locating a GameBox because one of its sides is the newly activated line, and then deciding if the GameBox has just become completed. We’ll use the same method as we did for row and column to find a GameBox - write a method GameBox.hasLine(type, column, row) and call it.

So no logic outside of GameBox needs to access the field sides. So you don’t need a getter for sides either. And since the list is final you can’t have a setter for it either.

You can follow the same reasoning with GameLine. You should find that you do need column and row as fields, because that’s how we locate them in the cache, but you don’t need getters or setters for them. You’ll need a getter and setter for activated.

See what you can do with that.

Update June 4th

Most of your issues are small.

Intellij is reporting a ton of package issues. You’re not using any framework like Gradle, which would provide project structure but let’s not go into that. Just make sure that everything is in the same package, then life is a lot easier.

Ditch the LineType inner class in GameLine. Just use an external Enum for it. Once again, this just makes life easier as inner Enum’s are a pain to deal with:

public enum LineType {

HORZ, VERT

}

I’m gonna give you the code for GameBox and GameLogic, because going over it item by item and describing how to resolve it is going to be really tough. I strongly suggest that you look at your code and the new code side-by-side and understand what the differences do.

I didn’t want to, but some of the forEach() stuff was just easier using Streams. I don’t know if you’re ready for Streams, but if they are beyond you, we can write more conventional for() loops to do the same thing.

Here’s GameBox:

public class GameBox {

int column;

int row;

private final List<GameLine> sides = new ArrayList<>();

BoxOwner boxOwner;

private enum BoxOwner {

PLAYER1, PLAYER2, NONE

}

public boolean isAtLocation(int column, int row) {

return ((this.column == column) && (this.row == row));

}

GameBox(GameLine line1, GameLine line2, GameLine line3, GameLine line4) {

sides.addAll(List.of(line1, line2, line3, line4));

this.boxOwner = BoxOwner.NONE;

this.completed = false;

}

public boolean isBoxComplete() {

return sides.stream().allMatch(gameLine -> gameLine.activated);

}

}

You don’t need the individual Lines any more, since you have sides. You need to move the BoxOwner Enum out of this class, so you can use it more easily in GameLogic.

I’ve also ditched the completed field, as it’s just as easy to check to see if all of the sides are activated. Once you take the Enum definition out of here, you can see that this class is almost trivial.

Now GameLogic:

public class GameLogic {

private List<GameBox> boxs = new ArrayList<>();

private final List<GameLine> gameLines = new ArrayList<>();

private final List<GameLine> gameBoxs = new ArrayList<>();

void runGame() {

}

GameLine findOrCreateGameLine(LineType type, int column, int row) {

return gameLines.stream()

.filter((GameLine gameLine) -> ((gameLine.type.equals(type)) && (gameLine.column == column) && (gameLine.row == row)))

.findAny()

.orElseGet(() -> {

GameLine gameLine = new GameLine(column, row, type);

gameLines.add(gameLine);

return gameLine;

});

}

void populateBoard(int maxColumns, int maxRows) {

for (int column = 0; column < maxColumns; column++) {

for (int row = 0; row < maxRows; row++) {

GameLine topLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.HORZ, column, row);

GameLine bottomLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.HORZ, column, row + 1);

GameLine leftLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.VERT, column, row);

GameLine rightLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.VERT, column + 1, row);

boxs.add(new GameBox(topLine, bottomLine, leftLine, rightLine));

}

}

}

void activateLine(LineType type, int column, int row) {

long startingCompleted = countCompletedBoxes();

GameLine gameLine = findOrCreateGameLine(type, column, row);

gameLine.activated = true;

if (countCompletedBoxes() == startingCompleted) {

flipCurrentPlayer();

}

}

private long countCompletedBoxes() {

return boxs.stream().filter(GameBox::isBoxComplete).count();

}

private void flipCurrentPlayer() {

}

}

Like I said, the Stream in findOrCreateGameLine() might be a bit advanced. We can change it. Basically, it does exactly what the method name says.

You had a lot of activated stuff in your method definitions, you didn’t need any of it. Watch out for “==” vs .equals().

Once again, for your own sake don’t just copy/paste this stuff into your project - try to understand how it works and make the changes manually. You’ll learn more.

I’ve left the game-play stuff beyond activateLine() empty. You’ll need to introduce an activePlayer field in GameLogic and make it of BoxOwner (which you need to move out of GameBox).

I also noticed a ton of errors where you used Box instead of GameBox. Box is a JavaFX Node type, which we’re not using. So if you type Box by mistake, it will take it, but it won’t be correct. You need to be careful about that.

June 6th

Here’s how to do the find line routine without a stream:

GameLine findOrCreateGameLine(LineType type, int column, int row) {

for (GameLine line : gameLines) {

if ((line.type.equals(type)) && (line.column == column) && (line.row == row)) {

return line;

}

}

GameLine newLine = new GameLine(column, row, type);

gameLines.add(newLine);

return newLine;

}

Watch out for “==” vs. equals()!

private void flipCurrentPlayer() {

if (this.activePlayer == BoxOwner.PLAYER1) {

activePlayer = BoxOwner.PLAYER2;

} else {

activePlayer = BoxOwner.PLAYER1;

}

}

List.containsAll() takes a second list and tells you if everything in the second list is in the first list. It doesn’t apply a question (a Predicate) to all the members of the first list, like you wrote it. But that is what Stream.allMatch() does.

public boolean isBoxComplete() {

// return sides.containsAll(gameLine.activated); - doesn't work

return sides.stream()

.allMatch(gameLine -> gameLine.activated);

}

You can write it like so:

public boolean isBoxComplete() {

for(GameLine line: sides) {

if (!line.activated) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

Your flipPlayer logic is absolutely correct.

There’s one step we’ve missed so far. We need to assign the newly completed boxes to a BoxOwner. Call this after the line is activated, but before the flipPlayer is called.

private void assignCompletedBoxes() {

for (GameBox gameBox : boxs) {

if (gameBox.isBoxComplete() && (gameBox.boxOwner.equals(BoxOwner.NONE))) {

gameBox.boxOwner = activePlayer;

}

}

}

BTW: If you want to get rid of the Stream in the count routine, you’d do something like this. Remove the second part of the if() condition and increment a counter that you return.

Remove the activated parameter from activateLine(). You don’t need it.

Now, take a look at this code from GameLogic:

void populateBoard(int maxColumns, int maxRows) {

for (int column = 0; column < maxColumns; column++) {

for (int row = 0; row < maxRows; row++) {

GameLine topLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.HORZ, column, row);

GameLine bottomLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.HORZ, column, row + 1);

GameLine leftLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.VERT, column, row);

GameLine rightLine = findOrCreateGameLine(LineType.VERT, column + 1, row);

boxs.add(new GameBox(topLine, bottomLine, leftLine, rightLine));

}

}

}

What do you notice about the columns of the Horizontal lines? What do you notice about the rows of the Vertical lines?

The Horizontal lines are in the same column as the box. The Vertical lines are in the same row!

Now you can figure out what row and column a box is in by checking its lines!

You’ll need this in GameBox:

public int getColumn() {

for (GameLine line : sides) {

if (line.type.equals(LineType.HORZ)) {

return line.column;

}

}

return 0;

}

public int getRow() {

for (GameLine line : sides) {

if (line.type.equals(LineType.VERT)) {

return line.row;

}

}

return 0;

}

Believe it or not, the game is ready to run! I added this to GameLogic:

void runGame() {

populateBoard(2, 2);

activePlayer = BoxOwner.PLAYER1;

playLine(LineType.VERT, 0, 0);

playLine(LineType.HORZ, 0, 0);

playLine(LineType.VERT, 1, 1);

playLine(LineType.HORZ, 0, 2);

playLine(LineType.VERT, 2, 0);

playLine(LineType.HORZ, 1, 1);

playLine(LineType.HORZ, 1, 2);

playLine(LineType.VERT, 2, 1);

playLine(LineType.HORZ, 1, 0);

playLine(LineType.VERT, 1, 0);

playLine(LineType.HORZ, 0, 1);

playLine(LineType.VERT, 0, 1);

for (GameBox gameBox : boxs) {

System.out.println("Column: " + gameBox.getColumn() + " Row: " + gameBox.getRow() + " Completed: " + gameBox.isBoxComplete() + " Owner: " + gameBox.boxOwner);

}

}

private void playLine(LineType lineType, int column, int row) {

System.out.print(activePlayer + " Type: " + lineType + " Column: " + column + " Row: " + row);

activateLine(lineType, column, row);

System.out.println(" Boxes Completed: " + countCompletedBoxes());

}

That runs the game illustrated under “Testing It”. Note that there is an error in the second image, the red line at (0,2) shouldn’t be there. So ignore it.

And I got this output:

PLAYER1 Type: VERT Column: 0 Row: 0 Boxes Completed: 0

PLAYER2 Type: HORZ Column: 0 Row: 0 Boxes Completed: 0

PLAYER1 Type: VERT Column: 1 Row: 1 Boxes Completed: 0

PLAYER2 Type: HORZ Column: 0 Row: 2 Boxes Completed: 0

PLAYER1 Type: VERT Column: 2 Row: 0 Boxes Completed: 0

PLAYER2 Type: HORZ Column: 1 Row: 1 Boxes Completed: 0

PLAYER1 Type: HORZ Column: 1 Row: 2 Boxes Completed: 0

PLAYER2 Type: VERT Column: 2 Row: 1 Boxes Completed: 1

PLAYER2 Type: HORZ Column: 1 Row: 0 Boxes Completed: 1

PLAYER1 Type: VERT Column: 1 Row: 0 Boxes Completed: 2

PLAYER1 Type: HORZ Column: 0 Row: 1 Boxes Completed: 3

PLAYER1 Type: VERT Column: 0 Row: 1 Boxes Completed: 4

Column: 0 Row: 0 Completed: true Owner: PLAYER1

Column: 0 Row: 1 Completed: true Owner: PLAYER1

Column: 1 Row: 0 Completed: true Owner: PLAYER1

Column: 1 Row: 1 Completed: true Owner: PLAYER2

There you go. If you can get that output, then you’re ready to start thinking about the GUI.

One last thing: My count has about 200 lines of code for all of this, even counting about 30 lines of testing code. That’s a tiny amount of code, IMHO.

Getting Ready to Add a GUI

Properties

Things that are to represented on the GUI dynamically need to be represented in the data as Properties. In this game we have the following data elements that need to be represented on the screen dynamically:

- Line Activation

- So we can change the colour of a line dependent on whether or not it has been clicked on and activated.

- Box Owner

- So we can show who owns a completed GameBox.

- Active Player

- So that we can display the currently active player.

A property is just a wrapper that goes around a value which makes it observable. This means that we can put a listener on it that will run some code every time it changes, or that we can bind it to another property.

The first thing that we’re going to do is to convert these 3 data elements to Properties and then update the rest of our code to work properly with them as properties.

In GameLine

We are going to convert activated in GameLine to a BooleanProperty. The important thing to note is that the property itself is going to be final, but the contents can change. Here we go:

final BooleanProperty activated = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

BooleanProperty is an abstract class, but SimpleBooleanProperty is a concrete class that inherits from it. So we instantiate SimpleBooleanProperty but treat it as a BooleanProperty. Got it?

Now, you’ll have errors all over your project. You have to change the way you access activated.

In order to get the current value of activated you need to call its get() method. So:

if (gameline.activated) {

do something;

}

becomes:

if (gameLine.activated.get()) {

do something;

}

You can’t assign activated with the = operator any more. No you need to use its set() method. So:

gameLine.activated = true;

becomes:

gameLine.activated.set(true);

In GameBox

We are going to change BoxOwner to a property. Here’s the declaration:

final ObjectProperty<BoxOwner> boxOwner = new SimpleObjectProperty<>(BoxOwner.NONE);

Now boxOwner is now a Property that wraps a BoxOwner value. You need to apply the same get() and set() changes to the rest of your code.

In GameLogic

Same deal with activePlayer. It needs to change from BoxOwner to ObjectProperty<BoxOwner>.

Testing it

Now you’re using JavaFX (the Properties), so you should be doing this on the FX Application Thread (FXAT). So we’ll modify the App class to run things in start() instead.

public class App extends Application {

@Override

public void start(Stage stage) throws IOException {

new GameLogic().runGame();

stage.setTitle("game fx");

stage.setScene(new Scene(new VBox()));

stage.show();

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

launch(args);

}

}

This will just be an empty box, but the game will play in the console and work.

At this point, we are ready to build a GUI.

Drawing Lines

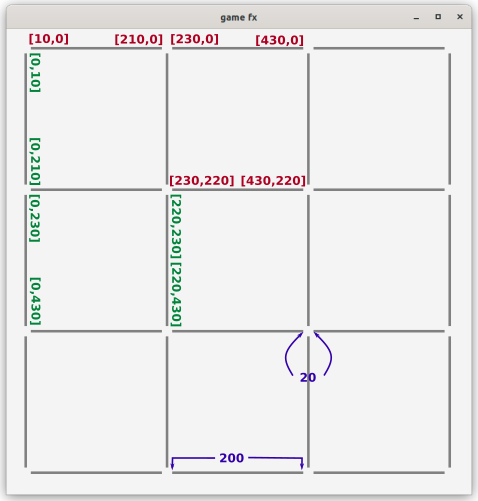

This is what we are trying to achieve:

Just the grey lines, not the annotations in red, green and blue.

This is done with a line length of 200px, and a gap of 20px. Note here that we’re not drawing the dot at all, since we really don’t need them if the lines are visible all the time. Later, if we really want to make the unactivated lines white (like the background), we can figure out how to draw the dots, which you would then need as a visual guide to where the lines are.

But for now, we’ll draw the lines in grey and then flip them to some other colour when they’ve been activated.

Once again, we have to handle vertical lines a little differently from horizontal lines, but it’s not that difficult.

Before we begin, we are going to use the JavaFX Node, Line. Line has 4 parameters in its constructor: x1, y1, x2, y2.

[x1,y1] defines one end of the line, and [x2,y2] defines the other end. So we need to know how to figure them out.

Let’s look at the first horizontal line. It goes from [10,0] to [210, 0]. For a horzontal line the following is always true:

y2=y1.x2=x1+lineLength

So all we need to figure out the correct values for x1 and y1 based on the row and column of the gameLine.

y1 is easier to deal with. On row 0 it’s 0. On row 1 it’s 220. So we can figure:

y1=row* (lineLength+gap)

Yah! That’s solved. Now on to x1.

In column 1 the value for x1 is 10 (which is 1/2 the gap). In column 2, it’s 230, and for column 3 it’s 450. So this is column times 220 + 10. So the rule for x1 is:

x1=column* (lineLength+gap) + (gap/2)

Vertical lines work exactly the same way, but reverse the rules for x and y:

- x2 = x1

- y2 = y1 +

lineLength - x1 =

column* (lineLength+gap) - y1 =

row* (lineLength+gap) + (gap/2)

Now we can determine x1, y1, x2 and y2 for any gameLine given its LineType, column and row. Which means we can draw the grid.

Creating the GUI

For now, we’re going to ignore the rest of your FXML framework, and just concentrate on creating a panel that shows the grid. And we’ll hard-code it to 3x3.

You need to do the following to your App class:

public void start(Stage stage) throws IOException {

GameLogic gameLogic = new GameLogic();

gameLogic.populateBoard(3, 3);

Builder<Region> boardBuilder = new GameBoardBuilder(gameLogic.gameLines);

scene = new Scene(boardBuilder.build());

stage.setTitle("game fx");

stage.setScene(scene);

stage.show();

}

Here we create the GameLogic and then get it started by calling populateBoard(3,3). That’s pretty straight-forward.

So what’s this Builder stuff? Builder is a standard JavaFX Interface. It just has one method called build() and we’re going to use that to create some sort of layout that we will put in the Scene. We’re using Region because it’s a generic JavaFX layout class that’s way, way up the hierarchy. So we can pass back an HBox, VBox, BorderPane, or anything else and it will still be Region, which is good enough to put into Scene.

Let’s look at GameBoardBuilder:

public class GameBoardBuilder implements Builder<Region> {

private final List<GameLine> lines;

private final double lineLength = 200;

private final double gap = 20;

GameBoardBuilder2(List<GameLine> lines) {

this.lines = lines;

}

@Override

public Region build() {

Pane pane = new Pane();

lines.forEach(gameLine -> {

Line line = createLine(gameLine);

pane.getChildren().add(line);

});

VBox results = new VBox(10, pane);

results.setPadding(new Insets(30));

return results;

}

private Node createLine(GameLine gameLine) {

}

}

The constructor takes the GameLines from GameLogic, and saves it in a field. The lineLength and gap are set up for you. Note that all of this coordinate stuff is double. I don’t know how you can have 2.5 pixels, but that’s just the way it is.

The build() method will cycle through the GameLines, and create a Line (that’s the JavaFX line Node) for each one. Then it puts it into the Pane. The Pane is stuffed inside a VBox just so we can set some padding around the Pane so that the Lines aren’t right up against the edge of the window.

So what you need to do is to use the rules above to figure out x1, y1, x2 and y2 and create a Line in the createLine() method.

You should also change the width of the Lines to something like 4 using Line.setStrokeWidth() and the colour to grey using Line.setStroke() (use Color.GREY). Just about everything you write should be inside createLine(). You should get something that looks exactly like the lines in my diagram above.

June 10th - Clicks on the Lines

First off, you should notice a few things:

- No Cell[][] Structures

- We’ve gotten all the way to almost done and there’s no GameBox[][] structure or GameLine[][] anywhere in our code. Everything is using the Java objects the way that they are supposed to be used.

- activateLine() is the Only GamePlay Method

- Once we’ve got the board set up, the only method that we need to call is activateLine(). The playLine() method is only there so that we get debugging output. This is gonna be super important

- The UI Populates from the Game Data

- You’ll notice that we don’t have nested for loops for rows and columns in the UI builder. We build from the data stored in GameLogic.

Clicking a Line (Adding an EventHandler)

This is super simple. You should notice that in GameBuilder.createLine() we have horizLine (or vertLine) and gameLine available at the same time. Your code is getting gameLine.column and gameLine.row, right? What you need to do now is to create an event handler for both horizLine and vertLine that sets gameLine.activated to true.

I have an article that talks about this stuff. You should read it, because it has everything that you need to know. So I’m not going to tell you how to do it here (unless you get stuck), but I will tell you that you need to call horizLine.setOnMouseClick().

Hint: You don’t need Event.getSource() or any of that kind of stuff. You have gameLine, use the Property.set() method to change activated to true. If you use a lambda, it’s 1 line!!! If you use an anonymous inner class, then it’s 1 line in the handle() method!!!

Enough of that. If you get stuck. Let me know.

Changing the Colour of a Line (Adding a Binding)

Once a line is clicked, you need to change it’s colour so that it looks activated.

Once again, I have an article about this, you can get to it from the “Bindings” section of this page. Read it, please. It will tell you what to do.

What you need to do is to bind the Stroke property of the Line to GameLine.activated. Once again, you have both gameLine and horizLine/vertLine available to you in the same code. So you can reference both of them.

First thing, get rid of the lines that call setStroke() and replace them with something like:

horizLine.strokeProperty().bind(SOME_SORT_OF_BINDING);

You need to create SOME_SORT_OF_BINDING. It needs to bind the GameLine.activated property, which is a BooleanProperty to return a Color value. I’d suggest Color.GREY for false, and Color.BLUE for true.

Just to make this totally clear, the computeValue() method of your Binding needs to call GameLine.activated.get(), and based on whether it’s true or false, return Color.BLUE or Color.GREY. This should make sense if you’ve read the articles.

If you get this far, you should be able to click on a line on the screen, and it should change from grey to blue. This is almost a completely working game!

Linking Clicks Back to GameLogic (Adding a Listener)

Let’s look at what we have here now: When you click on a line on the screen, it set’s the corresponding GameLine.activated property to true, and then that turns the line on the screen to blue. So, the screen is taken care of.

What about the GameLogic stuff?

Previously, we handled a game move by calling GameLogic.activateLine(). Now, we are activating the GameLines with the OnClick event of the screen line. So we don’t need the gameLine.activated.set(true) in GameLogic.activateLine() any more.

But we do need the logic that completes the boxes and determines if the active player needs to flip.

Since GameLine.activated is an observable Property, we can put a Listener on it. Once again, I’ve got an article that explains this stuff. So more reading, I’m sorry.

We need to do a few things:

- Remove all of the testing code that calls GameLine.activateLine().

- Change the name of GameLine.activateLine() to something like GameLine.handleActivatedLine().

- Remove all of the parameters from the method declaration in GameLine.handleActivatedLine().

- Remove the code that calls GameLine.activated.set(true) from that method, as well as the findOrCreateGameLine() call.

Now we need to put the Listener on GameLine. You do this when the GameLine is created in findOrCreateGameLine():

GameLine newLine = new GameLine(column, row, type);

newLine.activated.addListener(SOME_KIND_OF_LISTENER);

Once again, read the article I linked above. My suggestion would be an InvalidationListener that does two things:

- Call newLine.activated.get(). This re-validates the Property (explained in the article).

- Call handleActivatedLine() (or whatever you changed the name to).

If You Get This Far

You have a working game!!!!!

OK, you can’t see who owns the boxes yet, but if you put in some debugging code, you would see that the boxes are getting owned and the active player is getting flipped and everything is happening as it should.

Yesterday, you didn’t even have the lines painted. Now you have a working game. How cool is that.

Next, we’ll get the box owners displaying on the screen.

June 11 - The Rest of the Application

So now you have a working game, but you’re just missing the stuff that let’s the user pick the size of the board and start the game. This is the part that you can do in FXML. I’ll give you the code without FXML, and then you can figure out how to turn it into FXML.

A Word About FXML

As you probably know, I consider FXML and SceneBuilder to be a waste of time. I don’t use them, and I don’t think anyone else should either.

The only “benefit” (note the extreme sarcasm here) to FXML is that it let’s you use SceneBuilder. The cost for SceneBuilder is FXML and the ridiculous complexity that it adds to your application.

People that tell you that FXML helps you keep your logic separated from the UI are blowing smoke out their bums.

You just wrote a game that has 100% of its logic separated and independent from the UI. I mean, the name of the class is called GameLogic! And you know that it works without the UI because you had it running without a UI!

Applications have separation between components like the UI and the logic because the programmers engineered them that way. Not because some framework “encouraged” separation. And they are engineered that way because the developers understood the benefits of architecting the system with that separation.

Your game was engineered that way because I knew it needed to be like that before we even wrote the first line of code. So I tried to guide you down that path.

I can pretty much guarantee you that if your classmates are doing similar projects, there’s going to be a whole mess of business logic buried away in their FXML controllers.

As to the value of SceneBuilder. I don’t see it. Anything you can build in SceneBuilder I can write in pure code in 1/2 the time. And if you have 200 lines of FXML and 100 lines of Controller, I’ll have about just 50 lines of code that does the exactly the same thing.

Anyways. End of rant. On with the coding:

A Wrapper Screen

I’m giving you actual code, instead of telling you what to do, with the understanding that you’re going to convert it into FXML using SceneBuilder.

Here’s an updated App class, with some wrapper stuff added:

public class App extends Application {

@Override

public void start(Stage stage) throws IOException {

Region root = stuffYouCouldDoInFXMLIfYouHateYourself();

Scene scene = new Scene(root);

stage.setTitle("game fx");

stage.setScene(scene);

stage.show();

}

private Region stuffYouCouldDoInFXMLIfYouHateYourself() {

BorderPane results = new BorderPane();

Spinner<Integer> columnSpinner = new Spinner<>(2,10,3);

Spinner<Integer> rowSpinner = new Spinner<>(2,10,3);

Button startButton = new Button("Start Game");

startButton.setOnAction(evt -> {

GameLogic gameLogic = new GameLogic();

gameLogic.populateBoard(columnSpinner.getValue(), rowSpinner.getValue());

Builder<Region> boardBuilder = new GameBoardBuilder(gameLogic.gameLines, gameLogic.boxs);

results.setCenter(boardBuilder.build());

});

HBox bottomBox = new HBox(6, new Label("# of Columns: "), columnSpinner, new Label("# of Rows:"), rowSpinner, startButton);

bottomBox.setPadding(new Insets(8));

bottomBox.setAlignment(Pos.CENTER_LEFT);

results.setBottom(bottomBox);

results.setMinHeight(600);

return results;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

launch(args);

}

}

I’ve taken care to write the stuff in start() so that it’s easy to translate it into FXML terms.

The wrapper class for the application is a BorderPane. I picked that because it’s easy to call setCenter() and replace the contents dynamically. You don’t have to worry about clearing out the old contents. So it’s simple.

You’ll see that all of the GameLogic/GameBoardBuilder stuff has now been moved into the OnAction EventHandler for the Button. So we create a new GameLogic and pass it our selected columns & rows stuff instead of the hard-coded 3 & 3, then we instantiate GameBoardBuilder and then call its build() method to create the Node that goes into BorderPane.setCenter().

The big thing to note is that the actual gameplay stuff is self-contained. This wrapper class doesn’t know about any of the inner workings of GameLogic/GameBoardBuilder and it never will. This is all good stuff.

Detecting End of Game and Score Keeping

End of game is fairly easy to detect: Count up all of the GameBoxes with owner == NONE, and when it hits 0 the game is over.

If it was me, I’d do it using Bindings, but that would involve turning GameLogic.boxs into an ObservableList and adding an Extractor. Honestly, at this point that would make your head explode. Not that it’s difficult, but you’ve already learned a lot in a short space of time.

So I recommend doing it as part of GameLogic.handleActivatedLine() and just manually updating the Properties. You need to add a new field to GameLogic - a BooleanProperty called gameOver, initialize it to false.

Then add a new method to GameLogic - call it checkGameOver(), have it return a boolean and call it from handleActivatedLine(), after the call to assignCompletedBoxes(). Something like this:

assignCompletedBoxes();

gameOver.set(checkGameOver());

In checkGameOver(), you loop through boxs and if any of them have bowOwner.get().equals(BoxOwner.NONE), then return false, otherwise return true.

Now you have a Property in GameLogic that always matches whether the game is over or not.

That’s step one.

Score Keeping

This is the same kind of process as GameOver. You need to create two IntegerProperty fields, one for each player initialized to zero. So:

IntegerProperty player1Score = new SimpleIntegerProperty(0);

IntegerProperty player2Score = new SimpleIntegerProperty(0);

Once again, these can only change when a line has been activated, so we need something in handleActivatedLine(). Let’s create a new method:

private int countBoxes(BoxOwer typeToCount) {

int results = 0;

for (GameBox gameBox : boxs) {

if (gameBox.boxOwner.get().equals(typeToCount) {

results++;

})

}

return results;

}

so now, the code in handleActivatedLine() looks like this:

assignCompletedBoxes();

gameOver.set(checkGameOver());

player1Score.set(countBoxes(BoxOwner.PLAYER1));

player2Score.set(countBoxes(BoxOwner.PLAYER2));

Hmmmmmmmm…. Maybe this could be better?

This is called “Evolutionary Design”. What does checkGameOver() do? Do we need it any more? No we don’t. So delete it if you’ve already written it. Now you can do this:

assignCompletedBoxes();

gameOver.set(countBoxes(BoxOwner.NONE) == 0);

player1Score.set(countBoxes(BoxOwner.PLAYER1));

player2Score.set(countBoxes(BoxOwner.PLAYER2));

With me so far?

At this point, we’re at a crossroads. You have 6 dynamic properties in GameLogic:

- boxs

- gameLines

- activePlayer

- gameOver

- player1Score

- player2Score

IMHO, this is getting a bit much. All of those properties need to be passed to GameBoardBuilder in order to use them. And if we add anything else, like player names, then it’s almost silly.

The right way to do this is to take all of these properties and put them into their own class - call it GameData, then just instantiate that as a field in GameLogic, call it gameData.

Now you reference boxs (can we please fix the spelling of that to “boxes”!) as gameData.boxs, and so on. Then you just pass gameLogic.gameData to GameBoardBuilder in its constructor. You’ll have to update all of the references in build() to go through gameData, too.

This is nice because GameData actually represents the “State” of your UI, and it’s really good to have it in one place of its own.

If you don’t want to do that, it’s not the end of the world.

End of Game Display

This is tricky to describe, but I’ll try:

You need to create a container for the end of game display. I’d suggest a VBox with two Labels in it. The first one needs to be bound to player1Score and player2Score through a custom binding that compares them and returns “Player 1”, or “Player 2” depending on which is bigger. The second Label just says “Wins”. You’ll need to mess with the fonts to get it big enough. Let’s call this VBox, gameOverBox. Create it in the build() method of GameBoardBuilder.

Here’s the tricky part:

In GameBoardBuilder, in the build() method change the name of that VBox from results to gameBoard. Create a new StackPane called results. Put the gameOverBox and gameBoard into results.

StackPane puts things on top of each other, all centred. Now you need to control the Visible properties of gameOverBox and gameBoard so that only one is visible at a time. Like so:

gameBoard.visibleProperty().bind(gameOver.not());

gameOverBox.visibleProperty().bind(gameOver);

You can see that the Visible properties of each container are mutually exclusive, so only one will be Visible at a time.

That should work. I’ll let you figure out the custom binding for which player wins. Here’s a hint, you need to pass it both player1Score, and player2Score and send them both to super.bind().

Good Luck, and let me know if you get stuck.

StackPane Visibility Example

Try this:

public class HiddenStackPane extends Application {

@Override

public void start(Stage primaryStage) {

primaryStage.setTitle("StackPane Hiding");

primaryStage.setScene(new Scene(createContent()));

primaryStage.show();

}

private Region createContent() {

BooleanProperty fred = new SimpleBooleanProperty(false);

Button button = new Button("Click Me");

button.setOnAction(evt -> fred.set(!fred.get()));

HBox hBox1 = new HBox(new Label("TEXT For 1"));

hBox1.setAlignment(Pos.TOP_LEFT);

HBox hBox2 = new HBox(new Label("BLAH BLAH BLAH"));

hBox2.setAlignment(Pos.BOTTOM_RIGHT);

hBox1.visibleProperty().bind(fred);

hBox2.visibleProperty().bind(fred.not());

StackPane stackPane = new StackPane(hBox1, hBox2);

stackPane.setMinSize(300, 200);

return new VBox(10, stackPane, button);

}

}

You can try commenting out the two binding statements. Or just one of them.

So you should see how this works.

The idea is that the layout is static, but the configuration of the elements is bound to the data Model, which in this case is just a single Property.

Binding the Winning Player

You can’t have side-effects in a custom binding (at least you shouldn’t have)! So you can’t do stuff like Label.setText() in computeValue().

In computeValue() you use the bound values, plus whatever else you’ve set up via the constructor, to compute a value of the type defined by the type of your custom binding. Whenever one of the bound values changes, it triggers computeValue() to run, and then uses that new value in whatever you’ve bound it to.

In this case, you are going to bind to the TextProperty of a Label. So the returned value needs to be a String. This means that your custom Binding needs to extend StringBinding. And computeValue() will return a … String!

static class GameOverBinding extends StringBinding {

IntegerProperty score1;

IntegerProperty score2;

public GameOverBinding(IntegerProperty score1, IntegerProperty score2) {

super.bind(score1, score2);

this.score1 = score1;

this.score2 = score2;

}

@Override

protected String computeValue() {

return "Calculated Value";

}

}

Here’s the shell.

Important point: You should never pass around more than you need to. Never.

In this case you were passing GameData and expecting GameOverBinding to extract the values it needs from it. GameOverBinding doesn’t need all of GameData, so you should extract the two Properties you do need and pass them to the constructor of GameOverBinding.

Also, it’s not really a “Game Over Binding”, it’s a “Winning Player Binding”. So you should probably change the name.